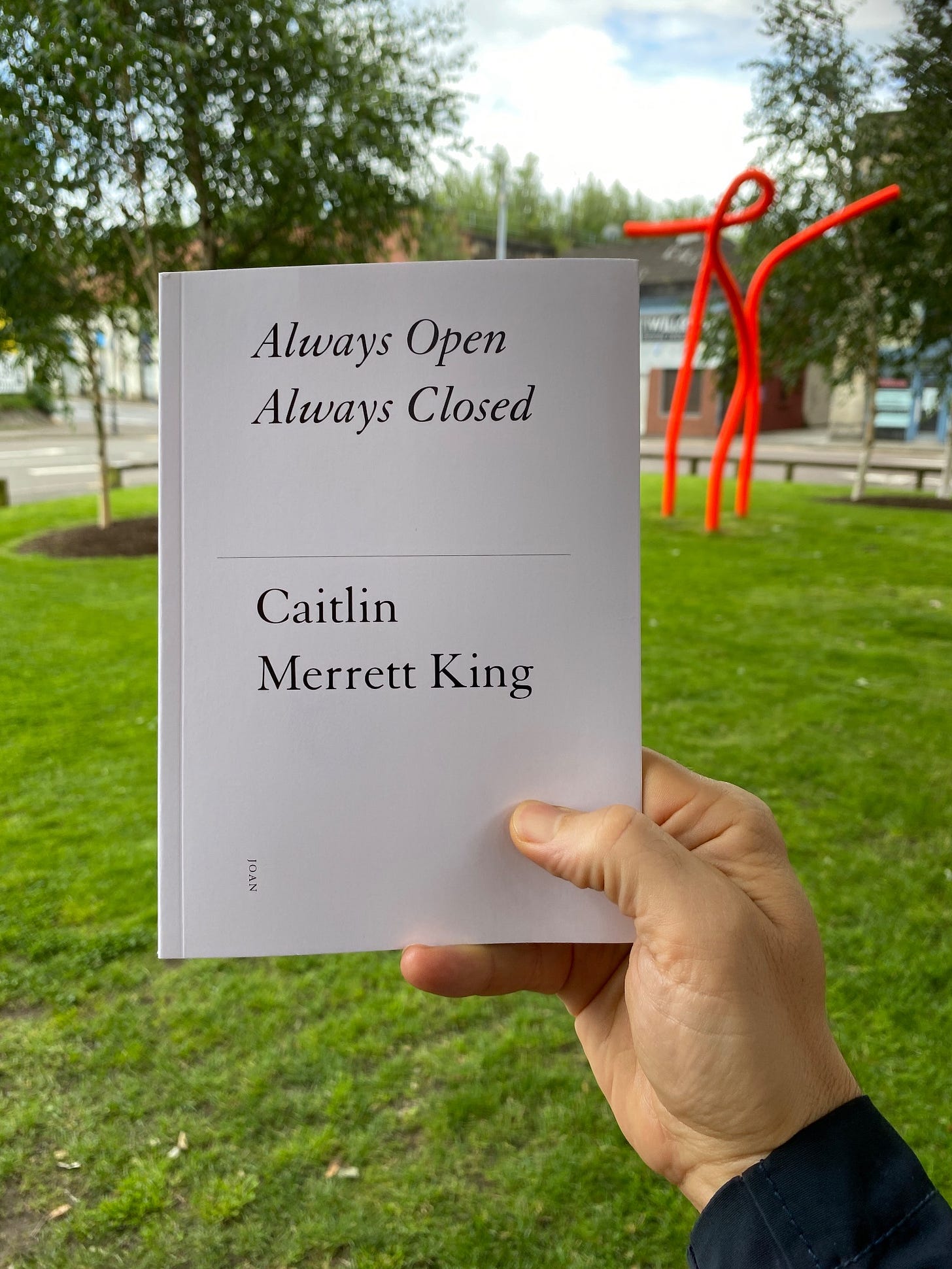

Book Review: Always Open Always Closed by Caitlin Merrett King

Metamodernism in the Glasgow art world.

In his Lectures on Literature, Vladimir Nabokov asserts that "one cannot read a book; one can only reread it." The initial encounter is like looking at a painting one small square at a time: there is no sense of the whole. It’s only when we reach the end that we can read the book with an understanding of how everything connects.

Always Open Always Closed by Caitlin Merrett King is a concise book, barely seventy pages of text, but it has a voluminous set of endnotes that point the reader to all the references. "What references?" I thought after I finished the main part. Then I read:

THE DIALOGUE IS COMPOSED FROM EXCERPTS OF THE FOLLOWING:

No wonder I was confused. I’d been reading the book as if the dialogue was her invention rather than fragments the author had consumed. In these endnotes, she lists people like Eileen Myles, Sarah Tripp, Dean Kissick, Maria Fusco, Red Scare podcast, Lynne Tillman, Sara Ahmed, and Lauren Berlant. Names that may mean nothing to you, but which, for the initiated, represent a vital canon of art writing and contemporary feminism.

The book follows Ms Real on her wanderings through the Glasgow art world. It is written in the localised third person, emulating Lynne Tillman's Madame Realism pieces of the mid-90s, which push criticism beyond pseudo-objectivity. Ms Real recalls

’s piece, “When Critics Use ‘I’,” which advocates embracing subjectivity with all its anxieties and unease. That article ends: "Want a challenge, scribe? Third-person art writing."Merrett King takes up the challenge with gusto. Ms Real eats vegan sausage rolls during the day and drinks free lager at exhibition openings at night. She wakes up hungover, uncaps the Berocca and compulsively checks her phone. It is a remarkably realistic depiction of life for the modern bohemian. The most valuable parts of the book are where Merrett King muses on art and art criticism:

On the Subway, she drinks a can of milky cold brew and reads a chapter from the ridiculously titled, How Glasgow Stole Contemporary Art. In the self-published compilation of his own articles, Alex Kennedy makes a pretty obtuse call for a 'return' to art criticism away from the emergent art writing that he has decided is incapable of real judgement and that rather than informing a public creates a 'smokescreen'. [...] He disagrees with art writing's ability to be critical, claiming that what art writers mainly do is just glorified PR for their friends and colleagues, which yes, Ms Real thinks, I guess sometimes this is true... but really this feels like a thinly veiled personal gripe.

Since postmodernism collapsed into a self-referential abyss, the general public lost interest in –isms. The art world, however, perseveres in trying to make sense of things with labels. The key –ism for this book is Metamodernism, a term that describes an oscillation between sincerity and irony. Metamodernism acknowledges relativity but does not reject the possibility of objective truths. For metamodernists, certainty is cringe and irony is poison; they want to navigate a way through.

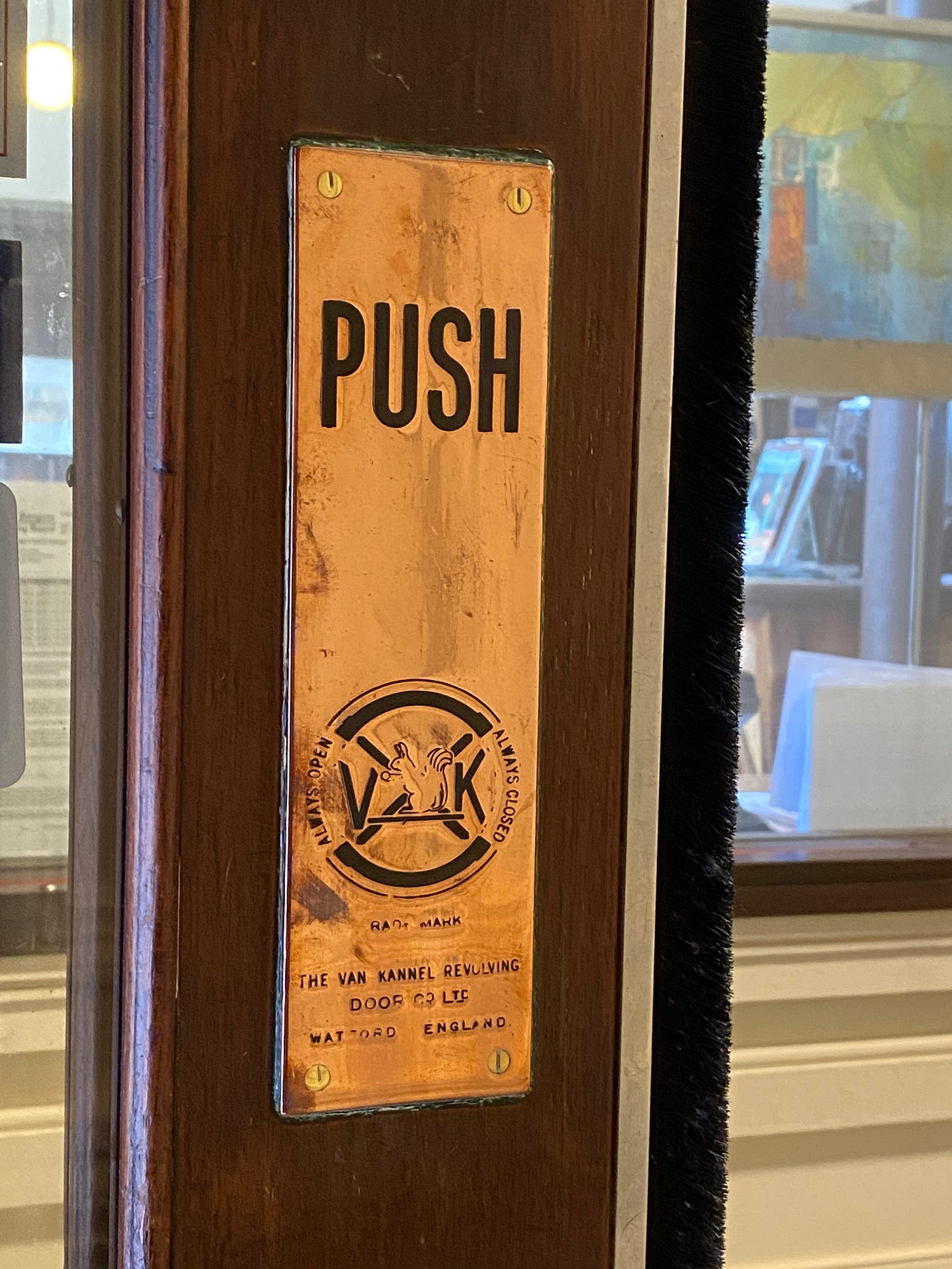

The title, Always Open Always Closed, is taken from the logo of the Van Kannel company revolving door in Cafe Gandolfi and sums up the ambiguity of the metamodernist era. We are contactable at all hours but can choose whether or not to reply. At its best, this kind of writing has “negative capability,” the phrase Keats used to describe how Shakespeare could contain so many perspectives without grasping after facts and reason. Or it could just be because we are unwilling to commit:

Ms Real thinks about how she can never decide if she really likes anything and really wishes that she could come to more conclusions. Understanding this well however, she knows that maintaining this approach means that you can avoid upsetting anyone or saying something that you or anyone else might disagree with later.

Sitting on a bench in the small patch of grass next to The Modern Institute, I read this elegant book in just over an hour. A seagull watched me. A dog bounded up to lick me. A young guy swigging from a bottle of Buckfast asked me for directions. Yet my concentration never wavered. Even in the third person, there was an intimacy in the voice that I found compelling.

After this first read, I got up to go to an exhibition opening at OUTLIER cafe. My sense of my surroundings felt sharper, alive to ambiguity. Even the Billy Connolly mural across from King Street car park felt resonant with meaning. This is what books should do, I thought, they should act on consciousness like a drug. It is well worth a (re)read.

Now that you’ve read my review, check out my short interview with Caitlin Merrett King.