For as long as I had words to make an argument, I have played devil's advocate. It always seemed more challenging to argue for the 'wrong' side of a debate—and more instructive. If your converser couldn't defend a point then maybe there were flaws in their position and, if they could, then you'd learn something.

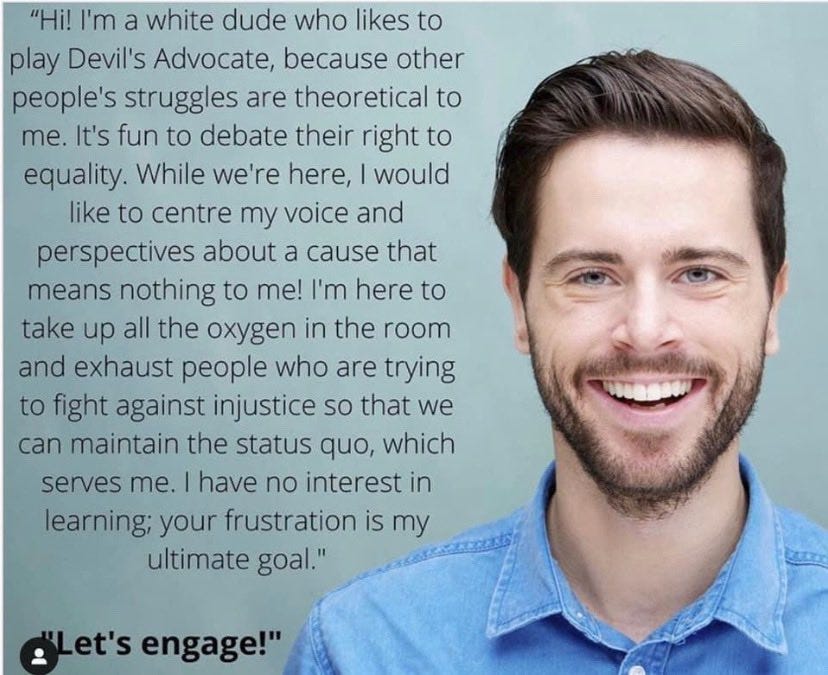

Only during the BLM protests in 2020, when someone posted the meme below — not to me, thankfully — did I realise quite how annoying it could be to have a conversation with someone like me.

What I like about this meme is that it does what good comedy should do by taking a tendency someone has observed in the world and condenses it into a jibe against a recognisable type.

I hope that I am self-aware enough to know when it is inappropriate to play devil’s advocate, but I worry that I just can’t help myself. Perhaps this tendency is part of the neurodiverse spectrum, like autism and ADHD, that we should learn to embrace. If it is, there is a ready-made term to describe it: cognitive decouplers.

What is cognitive decoupling?

Sarah Constantin, whose 2014 post brought Keith Stanovich's phrase to the rationalist blogosphere, describes cognitive decoupling as "the ability to block out context and experiential knowledge and just follow formal rules [...] It’s the ability to separate, to view things in the abstract, to play devil's advocate."

The term gained wider prominence when John Nerst, a Swedish erisologist (someone who studies how people disagree), used it as a way of discussing Sam Harris’s debate with Ezra Klein about Race and IQ. For Nerst, there are high-decouplers and low-decouplers and not recognising these tendencies leads to misunderstandings:

To a low-decoupler, high-decouplers’ ability to fence off any threatening implications looks like a lack of empathy for those threatened, while to a high-decoupler the low-decouplers insistence that this isn’t possible looks like naked bias and an inability to think straight.

Jimmy Carr’s Joke

This week saw outrage over Jimmy Carr’s joke about the Nazi genocide of the Gipsy Roma Traveller (GRT) community. The reaction showed what happens when you talk about fraught, emotive subjects in a way that is disconnected from individual and historical experience. The joke became controversial when posted as a 32 second clip on TikTok and Twitter:

Stripped of all context, the joke is horrific — suggesting that GRT genocide is a good thing. MPs called for Netflix to remove the show with one councillor apparently calling for the audience to be prosecuted for applauding. For low-decouplers, context and good intentions don’t matter: toxic words are polluting the discourse.

I find it impossible to judge something on the basis of a 30 second clip, so I did what I would never usually dream of doing and watched Jimmy Carr’s special. What I saw was what I would call ‘comedic decoupling’, which is where a high-decoupler taps into the expectations of a low-decoupling audience.

The joke about the holocaust comes at the end of the hour of equally dark material. It is set-up by Jimmy Carr saying that this is a potentially career-ending joke, encouraging the audience to suspend their moral instincts. He pulls a funny face when mentioning the holocaust because he knows we know this is the worst thing ever. He then plays on the fact that GRT people are still subject to animus, so much so that over 13 million people voted for a party who made a manifesto commitment to make it easier to move travellers on. The post-joke deconstruction emphasises that the joke is being made to educate people to the fact that 500,000 GRT were killed by the Nazis. He finishes his set by making the case that talking about dark subject matters is cathartic and helps us to deal with dark moments in our own life. In short, I think there is enough context to show that this isn’t hate speech.

Is it possible to be a jester now?

The historical precursor to the stand-up comedian, the jester, was an outsider whose ability to make jokes and point out uncomfortable truths was reliant on them not being a threat to the rest of the court. There is a carnivalesque feeling in a great comedy, where the normal rules of society are suspended. This is fine when politicians are serious and comedy has no consequence, but, since 2016, it feels the world has been turned upside-down.

We are in a strange situation where politics is becoming infected by comedy tropes: Donald Trump is the shitposter-in-chief and Boris Johnson uses humour as a way of endearing himself to the public and deflecting attention from the consequences of his policies. At the same time, comedians like Joe Rogan have become the main source of news for millions of people and stand-up, like Hannah Gadsby’s, has become an opportunity to discuss trauma and ethics rather than aiming at cheap laughs. How can you be a jester in such a world?

Empathy

In Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, Richard Rorty argued that writers like Charles Dickens made the world a better place by depicting the marginalised and helping people to develop empathy. At this time of separation—from nature, from each other, in politics—this is the only way out of the impasse. Empathy for the GRT, empathy for the comedian’s position, empathy for the high-decouplers, and empathy for the low-decouplers. We can’t develop empathy without being exposed to different ways of thinking.

If you want to listen to an even more incoherent version of this article, check out the discussion on this week’s Wit Beyond Measure podcast.

Interesting piece Neil, links with something i was reading about Anarcho-tyranny. A states powerlessness to effect big things while ruthless in the oppression of small infringements