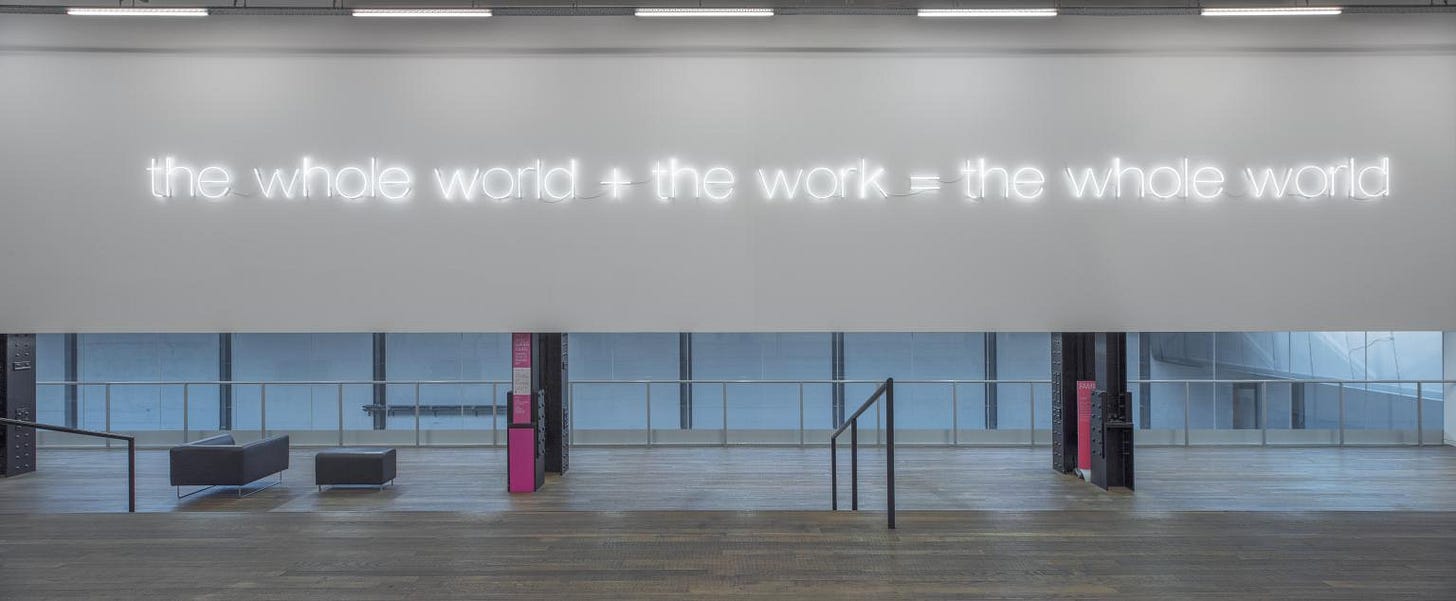

The world is changing all the time: people are born, people die and Heraclitus can never step into the same river twice. The idea that one human being could change the world seems like a confusion of terms. The conceptual artist Martin Creed summed it up in Work No.232, a neon equation stating 'the whole world + the work = the whole world'. We don't so much change the world as reconfigure it.

Perhaps a better title would have been 'How to improve the world', but how do we know what is better or worse? 250 years of industrial revolution has brought sanitation, speed, comfort and communication, but the side effects have been pollution, nuclear bombs, obesity and alienation. A pragmatic utilitarian might attempt to reduce overall suffering according to some measure, but what if the short-term reduction of suffering in one area increases suffering long-term in another?

For instance, whenever I see litter in the street my instinct is to pick it up and put it in the bin in order to reduce the amount of entropy in the world and avoid a ‘broken window theory’-esque societal breakdown. But then I hesitate, maybe my time might be better spent writing to the council about getting more bins and street sweepers. But then again, maybe we should address the underlying problem of why people litter in the first place - is it really just a lack of available bins or are the citizens of Glasgow particularly alienated? If they are alienated, is it because of deprivation, poor diet or lack of education? What would give civic purpose to the litterers? Should we try and help them all to become bourgeois - would they be happier? Or would it merely make them miserable on an existential level as well as a material level? It's at this point that I start wondering about the problems of capitalism, the distribution of wealth and whether communism inevitably ends in stagnation ... This is what I think when I see litter.

Any problem worth tacking is what Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber called, in their seminal 1973 paper Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, a wicked problem. The idea of wicked problems came from the sphere of social planning, as the failure of utopian housing schemes built along Corbusierian lines became obvious. Wicked problems have no engineering-led solution (unlike, say, the building of sewage systems to prevent disease), they are ill-defined (at what level do you tackle them?), involve political judgment (right and left tend to be differentiated by looking at either the symptom or the cause), are never solved once and for all (there's always more poverty, for instance), need a long time to see the effects (they have long half-lives), are unique to their circumstances (Scandinavian solutions won't tend to work in South America), and are always a symptom of a higher problem.

Evgeny Morozov, in To Save Everything, Click Here, has recently applied a similar criticism to Silicon Valley, showing how their attempts to solve the world's problems with smartphone apps, Big Data, nudges and gamification can actively undermine efforts at structural reform. If you want to change the world, you have to choose your level of focus wisely.

My contributions to the early issues of New Escapologist were focused on the individual and how they can take responsibility for their own decisions about consumption, work and pleasure. It is a libertarian view on change and improvement that fits in well with the neoliberal politics of our times. Indeed, for those looking for meaning at the top of Maslow's hierarchy of needs, it is very appealing. Yet the effects of neoliberalism on the wider society have been catastrophic - mental illness is increasing and there is a growing gap between rich and poor. We are surrounded by wicked problems, but the wickedest is what is the most effective use of your precious time on the planet.

The socially conscious Escapologist who wants to improve this situation must decide what odds they are willing to tolerate in order to do good. At one level, you could adopt an orphan and have a virtually guaranteed chance of making an effect (even if it is just through one individual). On another, you could write a book - which will have to compete with the 1.3 million books published in English each year, but could go on to be the new Das Kapital, Mein Kampf or Da Vinci Code.

The larger the scale, the more competition there is amongst memes, leading to the disheartening realisation that you can get more 'likes' on Facebook by posting a cat video than you can from writing an article on how to change the world. If this is the case, then why would you bother to go through the extra effort involved in the latter? Funny videos and status updates provide immediate gratification, whereas political change often means long-term frustration.

Worse still, the forces of capitalism have virtually unlimited advertising budgets and loads of manipulative tricks to distract and ensnare you. How can your efforts to change the world hope to compete with the intellectually repressive narcissism of Justin Bieber? Is there anything more futile than seeing someone selling the Socialist Worker on the high street? Ludicrous! Politics is a battleground of ideologies in which there is no longer any competition: the society of the spectacle is so all-consuming that, as Slavoj Zizek says, it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

If it is futile to hope for a revolution, perhaps it is better to work within the system as it stands and do the best we can. Peter Singer has recently been promoting the idea of Effective Altruism, using simple utilitarian economic arguments to save real lives. Starting from the premise that all life is equal and that we wouldn't ignore a child dying in our midst, he challenges us to give all we can to charities that save as many lives as possible. It takes $40,000 to train one guide dog, wouldn't that money be better spent saving a thousand Africans from going blind? Singer gives the example of Jason Trigg, a 25 year old who took a job at a hedge fund in order to give away hundreds of thousands of dollars a year to charity rather than working in a more ethical job where he could afford to give away much less. The problem with Singer's approach is that it often ignores larger issues, such as the effects of increased human population on the planet.

What is the way out of the impasse? How can we make the world a better place? The recent protests in Turkey and Brazil have shown that mass movements can catch fire in an instant, given the right spark. Such events make structural change possible because they help us remove the mental shackles that says it is impossible. As artist-campaigner Ellie Harrison said in the last issue of New Escapologist, the campaign to bring back British Rail is mainly an effort to make the idea of nationalisation thinkable again.

It is to be hoped that in the heat of protest alliances can be forged and political campaigns formulated. The great civil rights struggles of the twentieth century were not just about protest but also legislation - giving women the vote, black people equality, and gays legal access to each other’s bodies before the age of 21. The atomisation of society in interest groups means we no longer seem to have single causes to channel this energy into, so it is important to be tactical and take opportunities when they come. Only by accepting the difficulties of fixing wicked problems as a given and not something to be overcome or ignored can we hope to make any real improvement.