The ad hominem fallacy is difficult to avoid. Every time you meet another human being you get a sense of who they are and what they're about. We are apparently hardwired to like people who are symmetrical, funny, or who look like us. The result is that we live in an age of personality politics where who you are and what you look like are more important than your ideas. Who knows what Ed Miliband or David Cameron stand for? All that matters is how they come across.

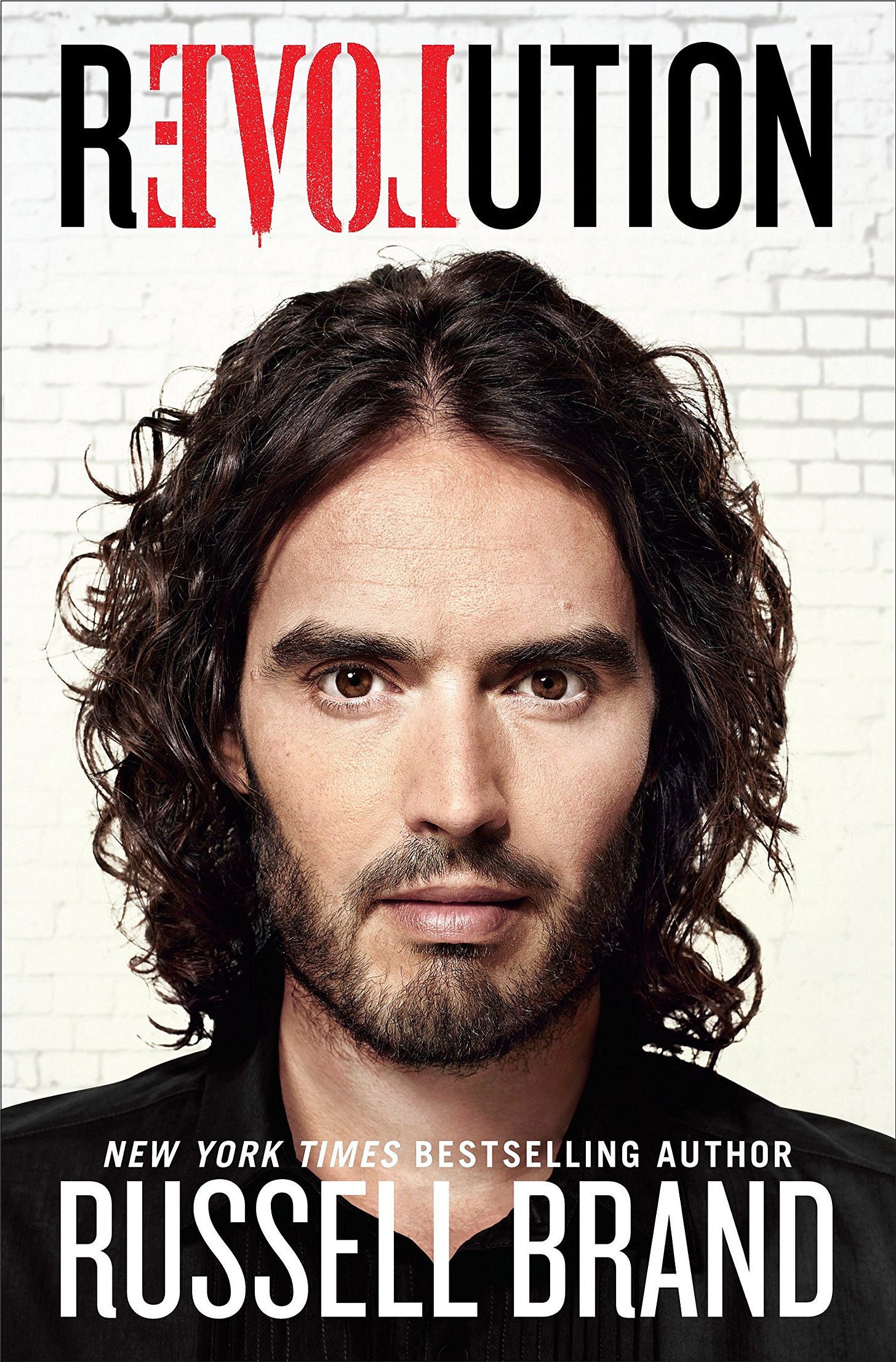

Take Russell Brand. At the time of writing (December 2014), Brand is everywhere and everyone has an opinion about him. The world seems divided between those who find him endearing and those who think he's an idiot. But very few people are willing to truly engage with his ideas. It is all about him as a person, as a celebrity, and whether he is a hypocrite, a popinjay and an egotist. To talk about ideas requires that we look beyond the individual to society as a whole, to history, to economics, to all the complicated processes that got us here in the first place. It also requires imagination.

Revolution is always impossible until it is inevitable. For most people reading this, things are alright. We live in comfortable houses and have access to cheap food and cheaper entertainment. We are trapped within the limits of our imagination, albeit an imagination that can be expanded via the magic of written language.

In his book, Revolution, Brand has a two-pronged approach to getting us to think about the present in a radical fashion. The first is to show how bad things are. He does this by revisiting the bleak Essex suburb of Grays, a world of pound shops and despair. The second is to show how unfair this situation is, highlighting the obscene wealth of richest people and how both rich and poor suffer the spiritual miasma of a life focused on consumerism, celebrity gossip, and social mediatised alienation. As Brand says: "We are imprisoned within, hypnotized without, denying ourselves access to the internal peace and external harmony."

No matter what you think of the present, it is your understanding of human nature that determines whether you think revolution is either possible or desirable. For optimists, the thought of change is easy. For those whose experiences have been negative, Brand counters with the example of the Stanford Prison experiment, in which good people turned evil when they were placed in roles that made them enforce unfair orders: we live in a society where zero-sum economic arguments inculcate selfishness, greed, resentment, and prejudice. No wonder people are pessimistic. But by changing the structures of society, the revolutionary says, we can change human nature.

It's at this point that skeptics usually start mentioning Pol Pot, Stalin, and Chairman Mao, supposed utopians whose efforts to change human nature caused catastrophic horrors. They might accuse Brand of suffering from the Dunning-Kruger effect, that stage in learning about a subject where people don't yet know what they don't know about and thus become overconfident. He hasn't been intellectually stultified by historical bloodshed or economic projections to think that this is the only way possible. He hasn't been jaded by the failure of previous attempts at amelioration. Brand still believes in revolution because what he is advocating doesn't involve military juntas and mass execution, instead it is a world reimagined to empower local communities.

This is going to be difficult to implement. The consequences of the industrial revolution and globalisation have been to create powerful and efficient networks to make things cheaper and lift people out of poverty, whilst destroying the planet. It has become a juggernaut of giant corporations, mowing down all in its path, whilst concentrating wealth in the few and treating the individual as a mere statistic. As Brand says:

Big, powerful structures must be overcome to bring about this new, gentler, more free society where we work less and have more leisure. Where technology is used to liberate the many, not to engorge the few.

For a vision of a more free society, Brand turns to George Orwell's description of anarchist Barcelona in Homage to Catalonia:

It was the first time that I had ever been in a town where the working class was in the saddle. Practically every building of any size had been seized by the workers and was draped with red flags or with the red and black flag of the Anarchists ... Every shop and café had an inscription saying that it had been collectivized; even the bootblacks had been collectivized and their boxes painted red and black ... Down the Ramblas, the wide central artery of the town where crowds of people streamed constantly to and fro, the loud-speakers were bellowing revolutionary songs all day and far into the night ... There was much in it that I did not understand, in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for.

The main criticism of loose communities based on democracy and participation tend to be overcome by huge military-industrial corporate governments. Nevertheless, there are examples where collectivism and participatory democracy do work. For the last 30 years, the Andalucian village of Marinaleda have been living in a kind of collectivised utopia. Elsewhere in Spain, unemployment has hit 50%, in Marinaleda it is under 5%. The society is structured around the needs of the people, not the needs of big business. As it says on the village's website:

By social democracy we mean unlimited access to all forms of well-being for the whole population of our village. We have always thought that liberty without equality is nothing, and that democracy without real well-being for real people is an empty word and a way to deceive people into believing they are part of a project when in fact they are not needed at all.

Marinaleda is an example of a community that didn't require a transformative revolution, just direct action and collective will to make things better. When reading in Brand's book and imagining what his revolution would mean, it is something like Marinaleda that I imagine.

The revolution will be small, beautiful, and take place in our hearts and our actions. We will join together and live life with integrity, set up small voluntary communities formed around common goals. Corporations would be reined in so that their power doesn't exceed that of the people they serve. Food production would be localised to create bonds in the community. All businesses would social enterprises owned by the workers. The health of the society would be judged by its vitality rather than its GDP.

Rather than voting away power to central government, people would be consulted on important decisions through referendums. The community would reflect the diversity of its members. The revolution wouldn't be a triumphal overnight separation from the status quo; we are too embroiled in the spectacle for that to happen. Instead, we must plant the seeds of new world in the cracks of the old system so that when it all falls apart, we are ready. Just imagine.

This article originally appeared in issue eleven of New Escapologist magazine.

Read my other New Escapologist articles.