“Adopted a pseudonym, things were never the same again.”

Leo Chadburn never dreamt of being a pop star, he never sang into his hairbrush or played punk rock in a friend’s garage. Growing up in the dour Leicestershire town of Coalville, he dreamt instead of making experimental classical music. So he “perved” over The Wire, studied music at college (specifically, the recorder), and wrote extremely reductive pieces, where if the song was about one chord that was all there’d be in the song. Leo explains:

“They were all very quiet and long and slow and were about disposing of your ego as a performer or a composer, so that there was no room for imposing an interpretation.”

After leaving college, he got bored and frustrated with this insular world and decided to do the exact opposite:

“I went from making very restrained music to very outlandishly theatrical music, from music that was very abstract to music for people to dance to in a club. But I didn’t want to be made by Leo Chadburn, so I adopted a pseudonym and, well, things were never the same again. ”

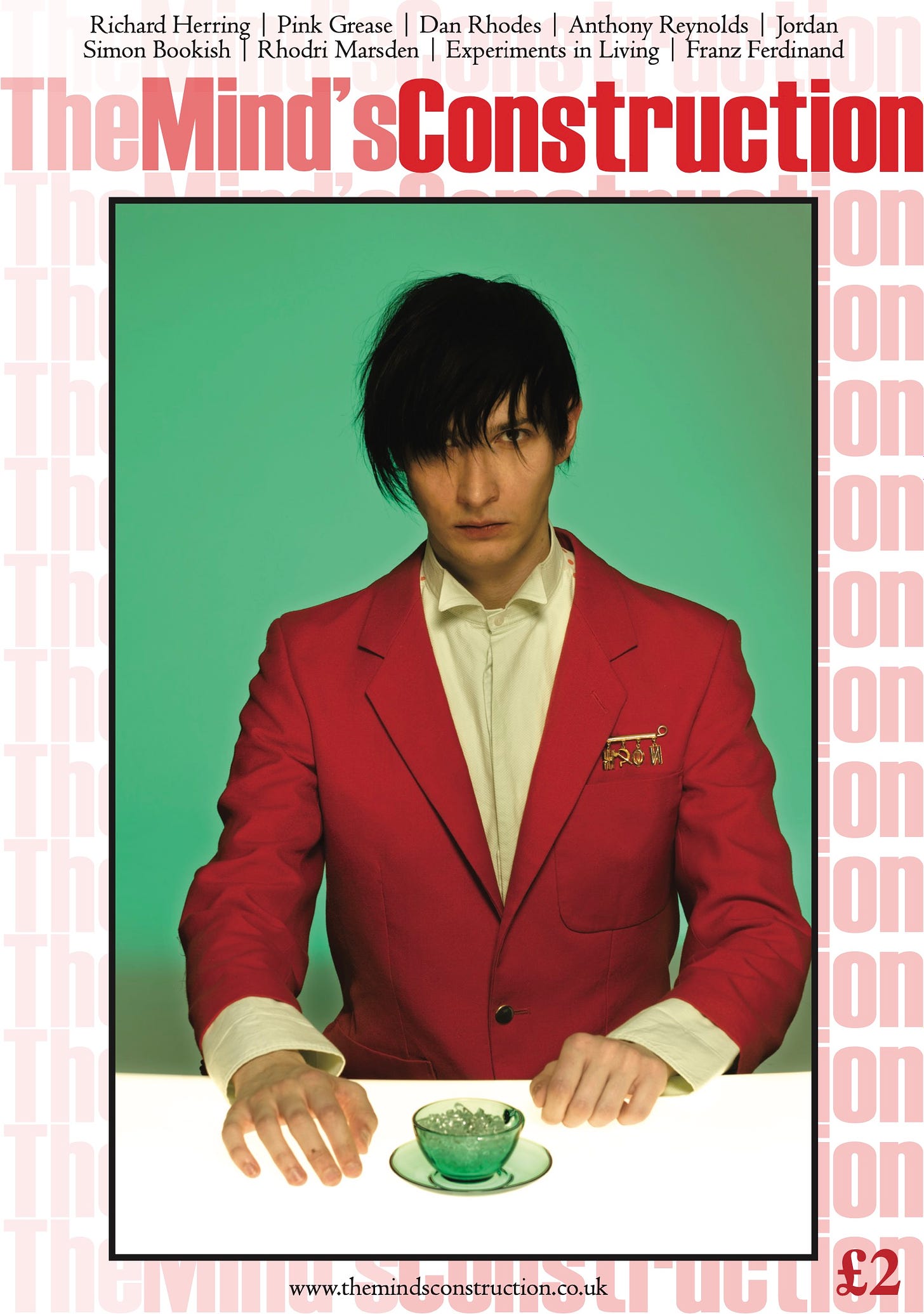

Simon Bookish is that pseudonym, a name currently best known for the electro cover version (or, in his own words, “shonky remix”) of Franz Ferdinand’s ‘Michael’, which recently appeared as a B-side to the single. It is easy to understand why Franz Ferdinand took a shine to him: like them, his music is both visceral and intellectual. Take ‘Terry Riley Disco’, which combines 21st century disco beats and with a reference to the arcane composer of minimalist music: “A mixed up joke for a mixed up world. A sonic combination that you’ve not yet heard, neither black nor white but somewhere between. We’re all shades of grey in a monochrome scene.” Is ‘Terry Riley Disco’ a manifesto?

“Yeah!” he laughs, “it is. It’s . . . erm. It is. It’s tongue in cheek. Writing within the style of functional dance music, where you’ve got all those which say: ‘we’re going to rock you, make your booty shake’. I wanted to write something that punctured that idea of music as your sales pitch. It’s kind of a joke. I’m saying that what I’m do is deliberately incongruous: Terry Riley Disco – something esoteric and beautiful and something quite physical and immediate as well.”

Do you not worry about going over people’s heads? Or of being too intellectual for the visceral classes and too visceral for the intellectual classes?

“If I was to do love songs or ‘come on everybody, dance dance!!’ sort of lyrics, it would have become quite boring for me almost immediately. It’s subverting it for my own entertainment, I don’t expect people to get all the lyrical twist and turns, but it makes it interesting for me to put together. I’m very easily bored. The whole idea of the Simon Bookish project is that it’d be something I could perform after years and years of writing music that was either for other people to play or for me to play but be very constrained. I wanted something that was more visceral.”

Bookish’s solo performance – just him and a laptop – is utterly compelling. He all instinct: sometimes leaving the stage to interact with the audience, other times looking as though he were doing avant-garde theatre. It is more like performance art than the flailing usually seen at gigs:

“I’m interested in how you can diorientate audiences, how you can alter atmospheres with very subtle things . . . and very blatant things. What I like about live performances is that you’re not just hearing the material outside of your own home, there’s something beyond that, something you never expected. Those exchanges of power that are quite interesting. I like to be disorientated and confused. The cheapest way to do that is to put down the mic and dance in the audience. Suddenly you’re just one of the people at the gig. The flipside of that is where I address one person, or the front row. It’s a really easy thing to do, but it changes the whole atmosphere of the room.”

Since adopting the pseudonym, he has built up a formidable body of songs – there’s the austere electro of ‘Videobooth’, the infernal disco of ‘Metal Horse’, and, the crowd favourite, the romantic post-human chanson of ‘Handsome Girls’. On that track, he sounds like Scott Walker locked in a room with Kraftwerk, discovering halfway through that he really wants to get out. I mention that there is an air of artifice, of self-consciousness, to Simon Bookish, that is combined with outrageous, instinctive eruptions . . .

“Things that are held up as quasi-outsider music,” he interrupts, “like Devendra Banhart and Joanna Newsom are actually quite self-aware. It has the feeling of being quite instinctual because it references music that has an air of spontaneity. You have to embrace the confusion because there’s no such thing as pure instinct anymore in the society that we live in with our constructed language and constructed codes of behaviour. In the same way as there’s no such thing as a pure unaffected intellectualism because we’re all animals.”

Indeed, there’s no way of escaping the body or the mind or of looking at oneself in the third person . . .

” . . . but we try again and again and again.”

Are you comfortable in your own skin?

“I am now.”

And you weren’t before?

“Well, no it’s just that I am big and weird looking and always have been. But I’m much more cheerful about being big and weird looking . . . I still get shouted at in the street every day. There was a great episode on the tube last Friday. There was this horrible scabby faced Mancunian with really red and peeling skin. Him and what I assume was his friend, both of them in their football strip, both with two male children. As I got on the tube the scabby faced man shouted:

‘Oi! Jarvis Cocker’

“Not that inventive. I ignored him and pretended I didn’t know who he was referring to. But then he started trying to get his children to laugh at me. Saying:

‘Look kids, look at his shoes: ha ha ha ha ha! Look at his fookin glasses, should have gone to specsavers.’ And all his children were going: ‘yeah, yeah he’s funny looking.’

“I thought, it’s one thing that you’re enough of an insecure boorish old fool to do this, but you’re encouraging your children! What twisted misconceptions are they going to grow up, if they don’t all turn out to be gay, which would be like divine punishment for you. I was wearing chipped white nail varnish as well, so that came in for some pointing at. Actually that was more nudging.

“I’m well used to it. But at least I’m not the pink-faced British public. At least I’ve taken a leap into the void that they know you want to as well.

I did wonder how you’d dress: whether you’d be . . .

“It’s not just dress, though, I can walk down the street with jeans and T-shirt and still be shouted at in the street.”

Do you really wear jeans and T-shirt?

“Erm, I don’t actually own any jeans, no . . . ”

Trainers?

“I don’t really, no. I dress down and it doesn’t make any difference. It’s quite celebratory. I realise what it was as well. I had some temp agency make some comment about my eccentric dress sense, which I sort of like them saying, but this was when I was wearing sensible clothes. And I wondered what the intangible thing was that makes some people stand out and some people not. I was fascinated by places that sell reality drag, like Austin Reed and I realise that what it is is that you are considered eccentric UNLESS you wear horrible clothes. Because if you buy a suit at Burtons, nobody will commment on it. It is actually a horrible, ill-fitting suit. Whereas if you are going to go to Saville Row or some young tailor, you’ll get shouted out in the street. That’s what it is. One of the many things that the British distrust: having an aesthetic, if you wear beautiful clothes, you’re weird.

Like many musicians, Leo is forced to work in a dead-end, menial job. What do you worry about when you’re at work?

“I worry about boredom, because I think it’s a really destructive thing. And I think that lots of people are resigned to being bored and regard it as an inevitable part of existence.”

What do you do to overcome boredom?

“Who knows? You can think of the money . . . A lot of people live like that. Always looking forward to something, rather than living each day as something valuable in itself. It doesn’t make you any happier. It’s a particularly London thing and British thing to do that.”

I heard you were thinking of moving to Berlin?

“It’s easier to survive there. But I feel quite British and like being around that English stoicism, that reserve. It’s quite an exotic thing. It’s interesting to observe. It’s why we have this lineage of great lyricists, people have got something really interesting to say. I worry if I moved to Berlin I’d become part of that whole vacuousness, that homongenous Berlin scene. There are so many interesting things going on musically, but not lyrically. Maybe it’s something to do with the atmosphere, the weather and dealing people with here. Boring jobs are quite inspirational for that. How people interact. Life is a little less difficult over there and that waters your art down a little bit . . . actually that’s rubbish, all that stuff about the suffering artist. I just need a holiday apart from anything else.”