Nicéphore Niépce

... and the origin of everything

I was supposed to write about Joseph Nicéphore Niépce this week. That was the plan. Niépce is commonly acknowledged to be the inventor of photography with his View from His Window at Le Gras being the first successful attempt to take light from the world and use chemicals to fix it on a plate.

The thing is, I don't know if there is much to add to the numerous accounts of Niépce you can find on the internet. Wikipedia exists so that we don't have to endlessly tell the same stories. We can provide a link for the curious and move on to something more interesting. Unfortunately for me that more interesting thing turns out to be an endless set of links.

I fell into the Wikipedia abyss... I looked up Niépce's photograph … and found myself reading about the camera obscura ... the evolution of the eye ... optics ... light ... electromagnetic radiation ... finally arriving at the Big Bang. If you want to explain an idea from the beginning and don’t start 13.7 billion years ago then maybe something is missing: the true origin. Niépce invented photography, sure, but to understand that invention we need to put it in context.

As a child, whenever we were given a cosmological explanation for the universe, my question was always: "But what came before the Big Bang?" Or: "Who created the Creator?" We are time-bound beings. Every moment has a before and after. Can you imagine a timeless, dimensionless realm? If I try, it instantly induces a meditative state. No wonder religions emphasise the immortal and everlasting. But something did happen: you, me, Earth, the universe, the multiverse, we came into being. Does it matter what origin stories we tell? Charles Jencks thought so.

Jencks became famous in the 1970s as the theorist of postmodern architecture. He believed that Modernism couldn't accommodate the diversity of human experience— that its rationalism was ultimately irrational—and favoured a more playful approach. His land art continues the anti-modernist theme: working with the earth and weather systems rather than trying to dominate them. He sought to show humanity as part of a larger story rather than an end in itself.

Jencks believed that terms like the Big Bang and the Selfish Gene diminished the beauty of the universe. They were, for him, individualistic Thatcher-era responses to elegant, natural processes. Likewise, the acronyms of Astrophysics—MACHOs and WIMPs—sounded to him like they were coined more for the amusement of nerds than for inducing a sense of wonder. Jencks spent the last few decades of his life (he died in 2019), exploring cosmological questions through his landforms. He would host seminars in which scientists would explain physics and evolution, and then try to illustrate those ideas in his Garden of Cosmic Speculation.

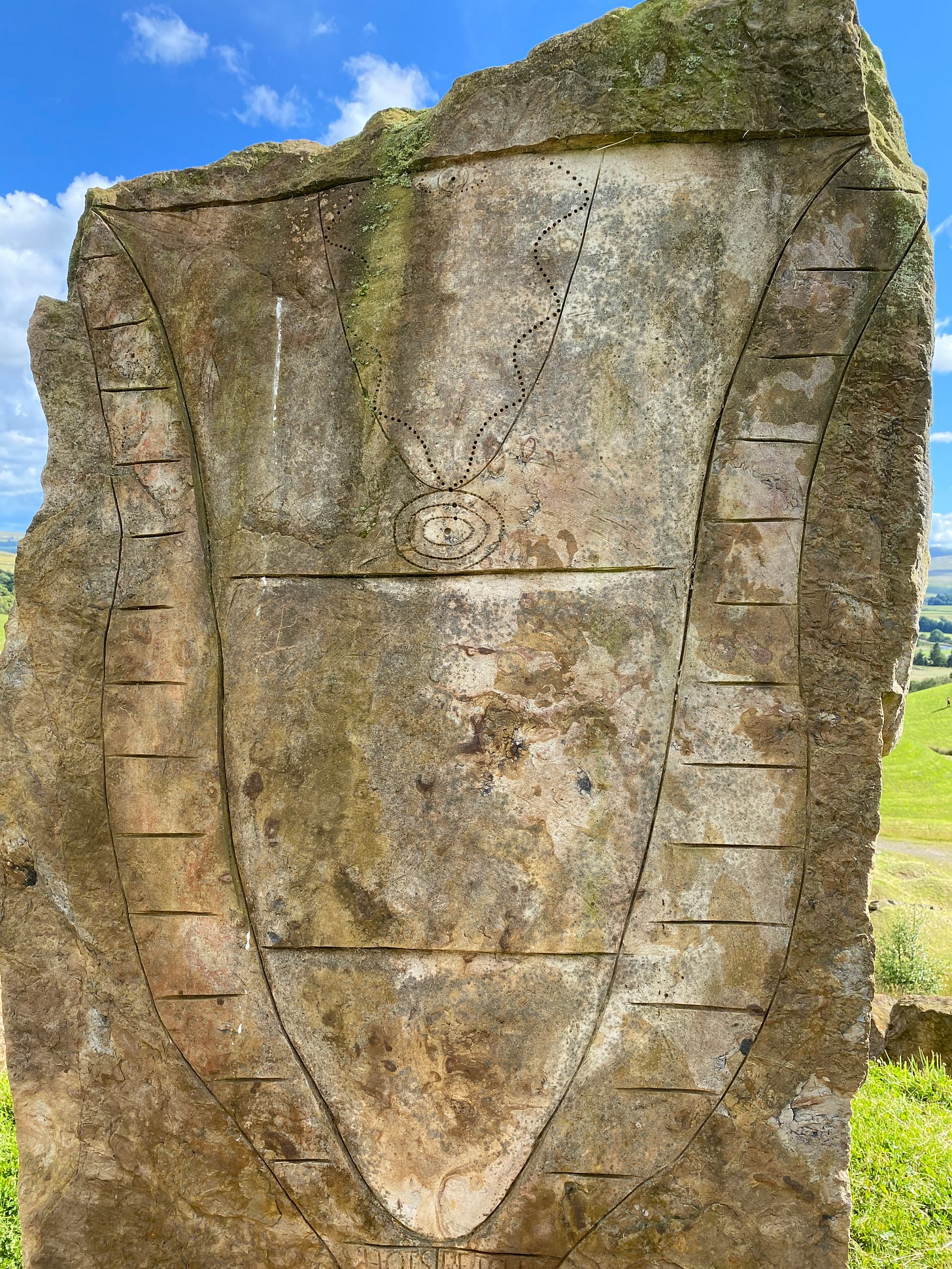

Last Saturday, I visited one of his final works—Crawick Multiverse (2015)—a vast land art project built on a former open-cast mine near Sanquhar. In it, Jencks uses the language of megaliths, those ancient early human monuments, to show the strange, fractal harmonies in the universe.

It's worth the day trip, even if the science flies over one's head. Merely as a visual spectacle, there is plenty here that is awe-inspiring. Indeed, one never feels optimistic nihilism, just endlessly curious.

In a roundabout way, this brings us back to Niépce, whose invention only happened because of his curiosity. He spent years experimenting with chemicals that might fix a permanent image and finally managed it in 1826. Like Jencks, Niépce sought to capture the fleeting and ineffable. As we’ll see over the next couple of weeks, photography’s invention feels inevitable, with others, like Henry Fox Talbot, evolving parallel systems, but Niépce was the first.

Post Script

As I was finishing this piece off, I came across a line from Hannah Arendt stating that “it is in the very nature of a beginning to carry with itself a measure of complete arbitrariness.” She continues:

Not only is it not bound into a reliable chain of cause and effect, a chain in which each effect immediately turns into the cause for future developments, the beginning has, as it were, nothing whatever to hold on to; it is as though it came out of nowhere in either time or space.

Consider this an arbitrary beginning.

I found Arendt’s quote in the new book by Bram E Gieben. Check out my photojournal, which coincidentally features a picture of Bram at his book launch.

The WIP #28

The Fair has come to town. I am fascinated by how they represent excitement through graphic design, while the people have to be professional.

Nice take. Here's another :) https://resurgencejourney.substack.com/p/what-was-the-first-photograph

I’ve never stumbled upon Charles Jencks before this post but I’m intrigued and must now look him up. Thank you.