5Things is a monthly breakfast event where people discuss non-fiction books they’ve found stimulating. The idea is to gently expand the mind before taking the world on. It has been going on since 2019 and they’ve built up an extensive archive of talks. On Wednesday, I spoke about The Photographer’s Eye by John Szarkowski.

The Photographer’s Eye by John Szarkowski

Why I chose this book?

At the beginning of the first lockdown, there was a lot of talk about what people had achieved during previous plagues. They would say things like “Did you know that Shakespeare wrote King Lear during a lockdown? What are you going to do?”

I started a daily photo blog. Every day I’d go for a walk and take photos. The next day I’d choose one of these and post it online. Just as a monkey can occasionally take an amazing selfie, I became convinced that I was taking great photos.

But the trouble with doing a project like this for a long time is that you become aware of the Dunning-Kruger effect: the idea that beginners are confident because they don’t know what they don’t know. The journey to expertise starts with becoming aware of what else is possible.

The Photographer’s Eye was the book that shattered my confidence. I found it challenging and awkward, disturbed by the possibilities it presented.

About John Szarkowski

John Szarkowski (pronounced Zshar - Cow - Skee) was the Director of Photography at MoMA in New York between 1962 to 1991. He was one of the key figures in convincing the world to see photography as a fine art rather than just a mechanical tool. In 2010, Sean O’Hagan in The Guardian could ask “Was John Szarkowski the most influential person in 20th-century photography?”

About the book

The Photographer’s Eye is based on a 1964 exhibition he curated of the same name. And is essentially an exhibition catalogue consisting of images without much exposition. The book has lived on in art schools as a set text for photography students, which I believe is where my wife got it and it was she who suggested I look at it.

5 Things about The Photographer’s Eye by John Szarkowski

1. The past must die for the future to be born

Whenever a new medium arrives early practitioners tend to try to fit it into their pre-existing mental models. Humans invented the car and called it a horseless carriage. They got the camera and made scenes that looked like paintings. Photography is not painting, but these associations took a long time to die.

Szarkowski writes about how the possibilities inherent in the medium were developed by non-artists: “silversmiths, tinkers, druggists, blacksmiths and printers.” The “new ways might be found by men who could abandon their allegiance to traditional pictorial standards or by the artistically ignorant, who had no old allegiances to break. [...] no common tradition or training [...] no academy or guild”.

If you are of a certain generation, you’ll know that this is exactly what web designers went through when we were learning how to build websites. There was a lot of time when the websites would look like a book or a magazine or had skeuomorphic elements pretending to be graffiti or wood. Often it was non-designers who learnt how best to serve the medium and transcend the old, stale metaphors. Szarkowski shows that to discover the possibilities of a medium you have to experiment without being burdened by the past.

2. The Road Not Taken

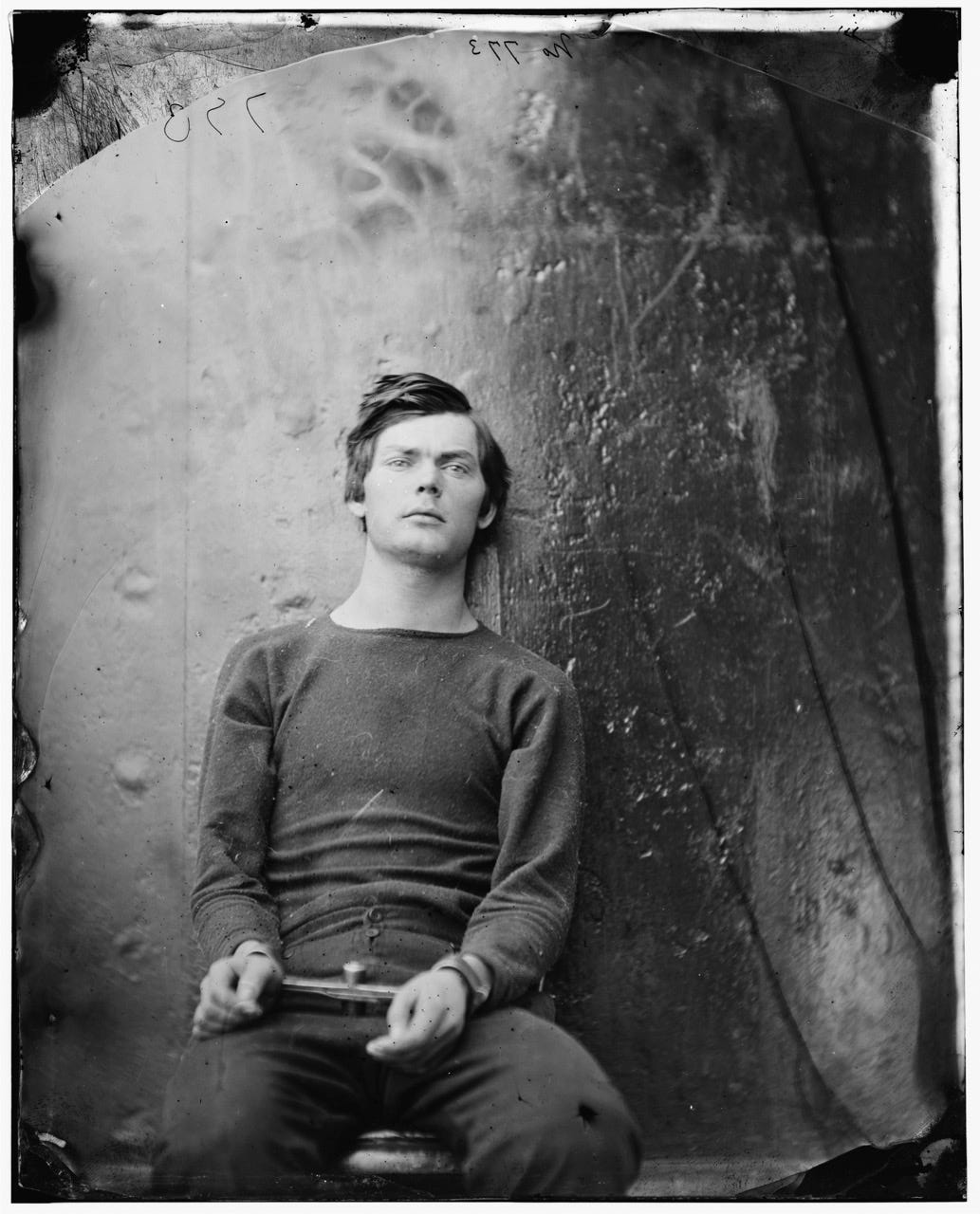

Because of all the early activity, it was difficult for art historians to establish a narrative about photography as they did with painting, especially in terms of formal innovation. You can still use old cameras and the photos feel new; you don’t have to use digital cameras. Whenever I see this photograph of an assassin from 1865, it just seems utterly contemporary. The eyes have a modern attitude, he is not playing a role.

The Photographer’s Eye is not a chronological history, but a thematic history. By mixing up the timelines Szarkowski reveals strange connections between different eras and photographs. This helps show some of the paths not fully explored. As he writes:

“The history of photography has been less a journey than a growth. Its movement has not been linear and consecutive, but centrifugal. […] It is in our progressive discovery of it that its history lies.”

At the moment, things like AI and crypto are associated with certain tendencies but this is unlikely to be the full story. What chance encounters can we find there? What meaning is up for grabs? What unexamined weirdness?

3. Physics is the law, everything else is a recommendation

When you first get into photography people talk about things like the rule of thirds. But these rules are just rules of thumb, not hard rules. They are rules of composition that have been established through conventions and conventions can become conventional.

The Photographer’s Eye throws out the rule book. It asks us to think about what happens if we do the opposite. What does it do to the emotional resonance of an image?

Not everyone was happy with his approach. In From Bauhaus to Our House, Tom Wolfe wrote:

Photography had always seemed to be a form of expression with an implacable obviousness to it. But [...] Szarkowski made a virtue of what had always been regarded as photography’s flaws: blurring, grotesque foreshortenings, untrue colours, images chopped off by the edge of the film frame, and so on. They achieved their goal; they managed to make photography utterly baffling to those unwilling to come inside the compound and learn the theories and the codes.

Wolfe seems to think that Szarkowski was trying to become a priest of photography, elevating it above the masses. But I think the best images in the book do what all art should do and appeal to the unconscious: the shiver down the spine that tells us what we like without knowing why.

4. In a world of abundance, curation is key

Photography is an invention of the industrial age. Almost overnight you could print millions of identical images.

Painting was difficult, expensive, and precious, and it recorded what was known to be important. Photography was easy, cheap and ubiquitous, and it recorded anything.

This is an especially important lesson in 2023. We have all these AI tools at our disposal that can create amazing things with a one-line prompt. We still need the taste to decide what to create and that's the real barrier to doing good work. Anyone can take a great photograph but can you curate a coherent series? Can you do it consistently?

Photography in the age of smartphones can become boring very quickly. I honestly don’t care to see another picture of a Scottish Loch (though I still take them). We take the same photos that say: “I was here.”

I read recently that are so many images of the moon that when you take a photo of the moon on a Samsung phone, the computational algorithm doesn’t actually use what is coming through your lens but uses other photos to create a fake composite.

When I look at my Instagram feed, I see everything taken from the same distance, fitting the frame in the same way. It can get samey. Szarkowski’s book opened up my sense of what is photographable, that amidst abundance, there are surprises to be found.

5. The camera is an instrument to see without a camera

Reality is a richer, more vivid place after seeing visions of it through the lens of photography. At its best, it is, as Dorothea Lange says, “an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.”

The book is divided into five parts—Thing Itself, The Detail, The Frame, Time, and Vantage Point—and I want to run through how each might help us to see the world anew.

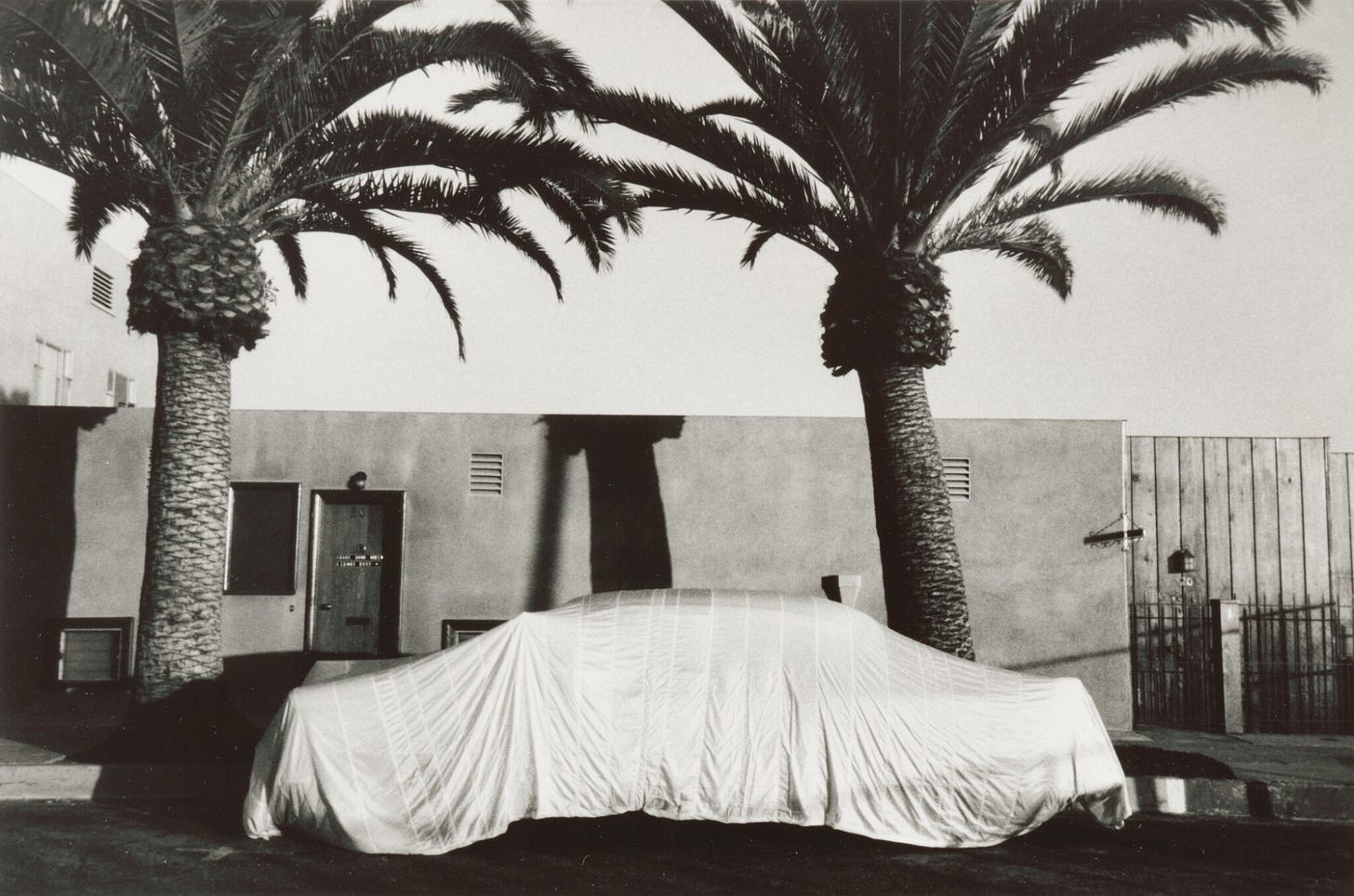

‘The Thing Itself’ shows how whatever is in the frame becomes a thing, whether it is intentional or not. Szarkowski also shows how an empty space is a thing. Robert Frank’s covered car is one kind of mysterious thing. Elliott Erwitt’s Fontainebleau Hotel, Miami Beach, 1962 is another kind of thing. What is the subject here?

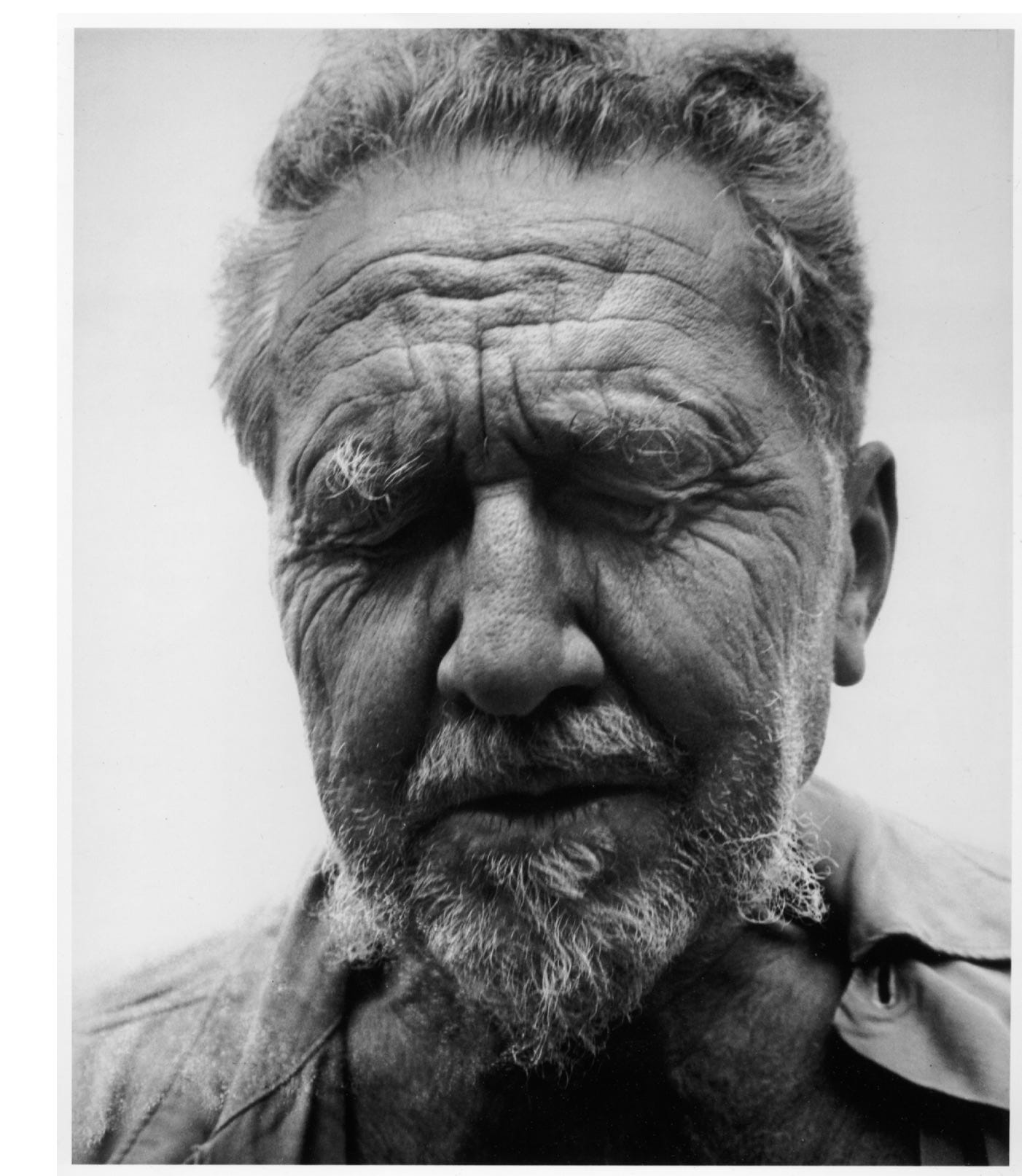

‘The Detail’ is about the symbolic quality of great photographs, where a significant detail has more meaning than it would if attempted to capture the entire scene. This Garry Winogrand photograph of an elephant takes on a charged quality for this reason.

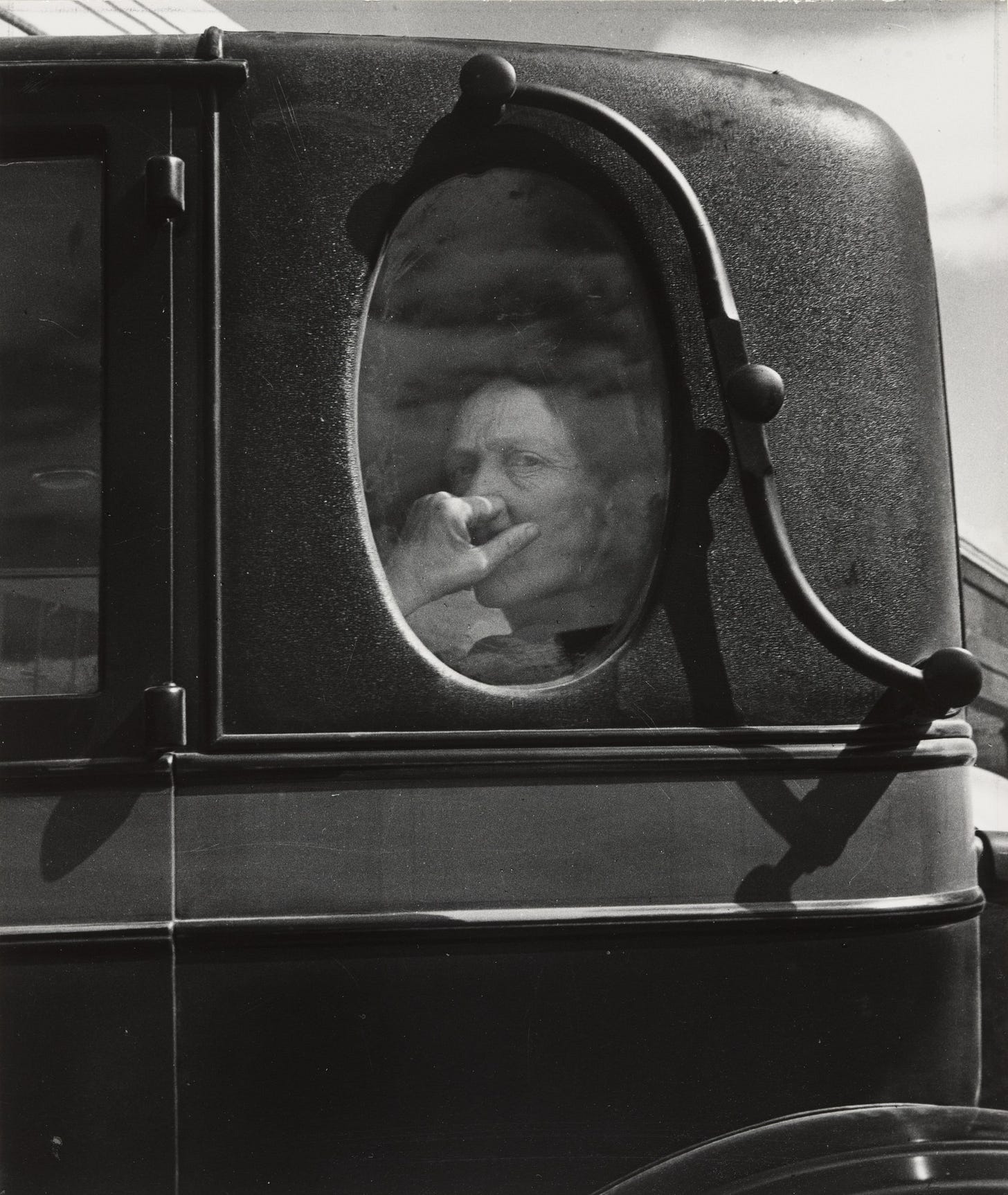

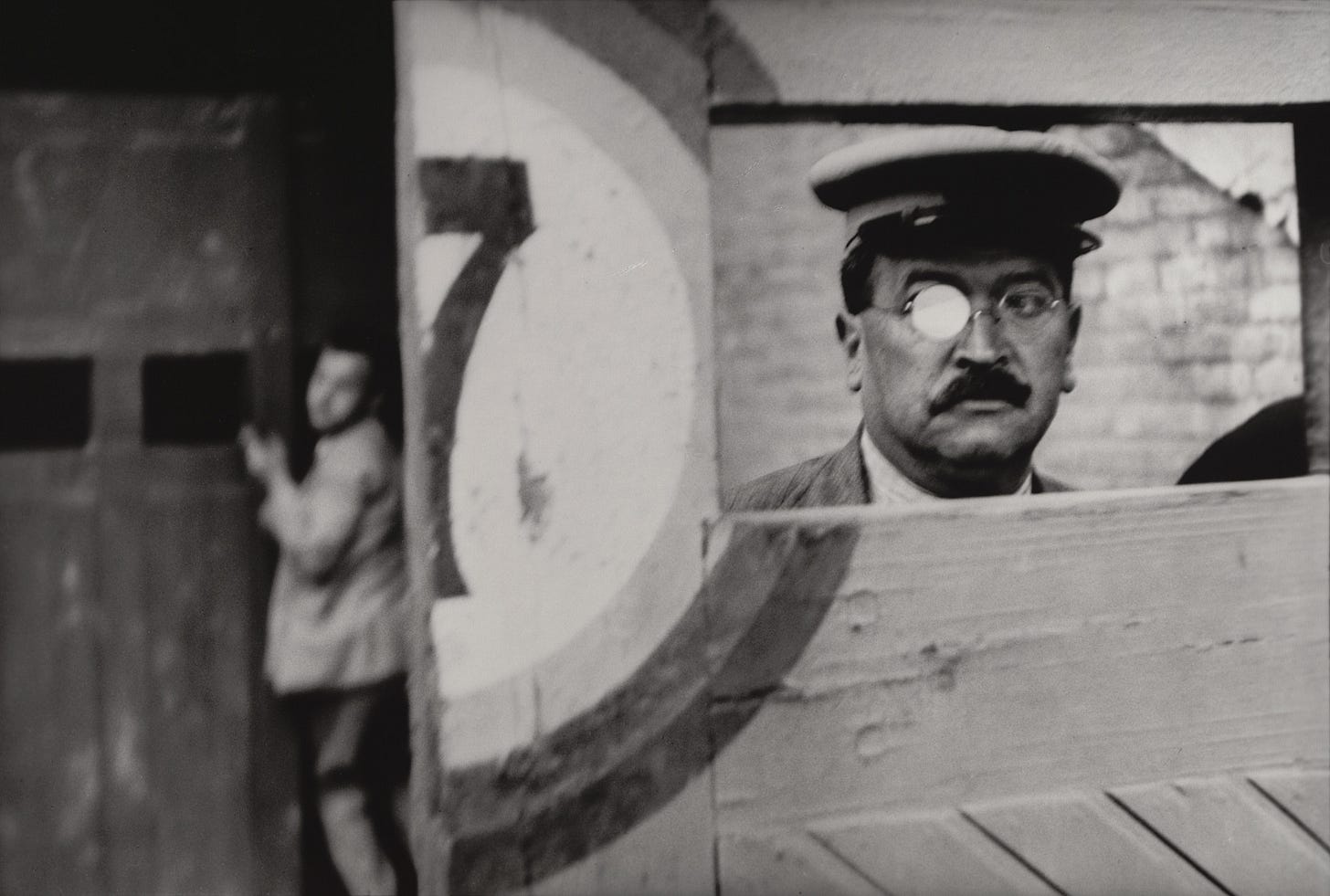

‘The Frame’ follows on from this and is about choosing and eliminating what goes in and out of the frame. By cropping, we can totally change the meaning of a photograph. Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photo here has frames within frames and a blurry child in the background who could have been cropped out to be neater but is far more powerful with that context. What are we editing out to be neat?

‘Time’ - many organisations have pivoted to video in recent years because the moving images are seemingly more engaging. Photography is a static medium but it can create a sense of psychological time through long exposures and a sense of capturing the action as it happens. This photo by Harry Callahan draws out dynamic qualities unique to photography.

The final section, ‘Vantage Point’, asks us to re-examine what it means to change perspectives. The selfie is taken from a specific vantage point: what does it do to us to have an arm that is a specific length? If you put the camera above you or below you, what does that do to your appearance? If I go to the top of a building or lie on the ground, what happens? This exercise reveals the truth that there is no objectivity in photography or in our gaze, just perspectives on the world.

I loved this piece, I enjoy other artists perspectives on their medium, I am not a photographer, I'm a poet, and read this article through a spiritual lens. "The past must die for the future to be born" hit me between the eyes = life is ephemeral, don't resist, let go. "The road not taken" = there is no growth without change. "Physics is the law.." = everything is energy and energy never lies. "In a world of abundance, curation is key" = be true to yourself and live with integrity. Finally "The camera is an instrument to see without the camera" = life is all about perspective and being able to adjust our own as we seek new truths and self development. Wonderful!

Great distillation. I really enjoyed this.