Everywhere I go online I seem to be assailed by jiggling women. My Instagram Explore page is populated by braless female golfers, my Facebook feed is dominated by videos of women with pronounced décolletage, and Threads presents me with a succession of steatopygic buttocks. Such videos are essentially advertisements for OnlyFans creators forced to be creative so as not to break the platform rules about what you can and cannot show. Meta won't allow "female breasts that include the nipple" unless that nipple is protesting, feeding a baby, or has post-mastectomy scarring. Hence, jiggling.

We are living in an age of accelerating addictiveness. Whereas opium was mildly addictive, modern opioids are 100 times stronger. The same is true of pornography. Whereas previously we only had to deal with the occasional titillating advert or billboard, nowadays every platform has millions of industrious sex workers.1

I think of the internet as the unconscious made manifest. We are curious (Google), we want to make friends (Facebook), and we think about sex. 10% of the top fifty websites focus on adult content. It is a huge business. Yet, thanks to platform guidelines and what remains of human decency, porn is rarely discussed. It’s difficult to define what is obscene — rules are often superseded by our visceral reaction — but to paraphrase Justice Potter Stewart, "we know it when we see it."

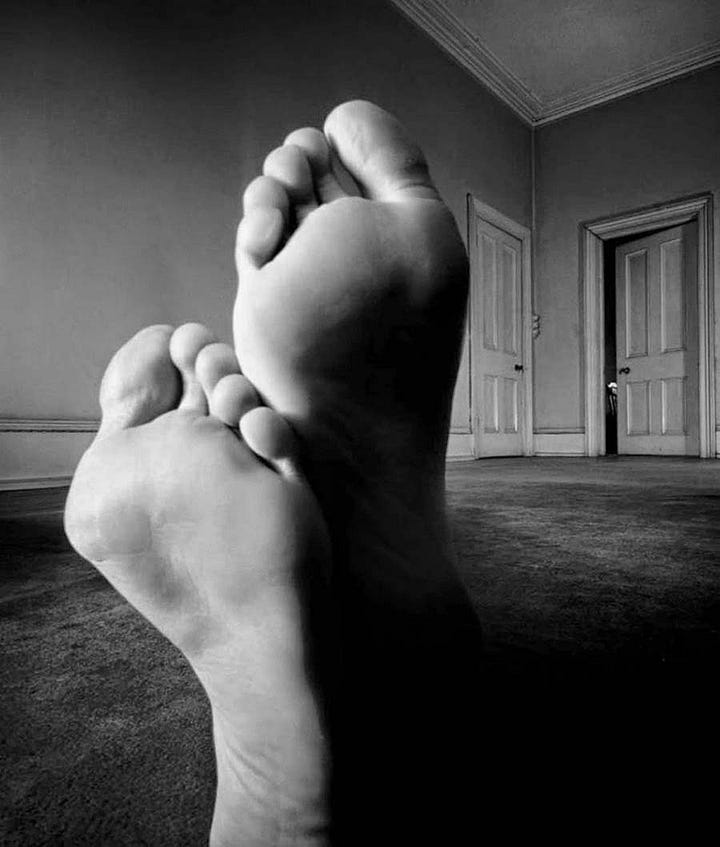

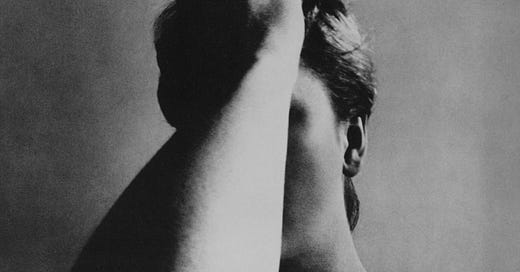

In such a climate, we turn with relief to Bill Brandt (1904-83), whose series of nudes are some of the greatest photographs of the twentieth century. I first chanced upon Brandt's nudes in John Szarkowski's The Photographer's Eye. These images ripped up the rulebook and expanded what was possible in photography.

Brandt was a modernist, but one born too late to experience its early radical phase. He assisted Man Ray in Paris, after having been introduced to the great photographer by Ezra Pound, then moved to England in 1933. Before and during the war, Brandt worked as a photojournalist for magazines like Picture Post and Lilliput exploring life in Britain. After the war, he mainly made portraits of artists and writers, as well as a series of extraordinary nudes, which were published in 1961, a year after the Lady Chatterley trial.

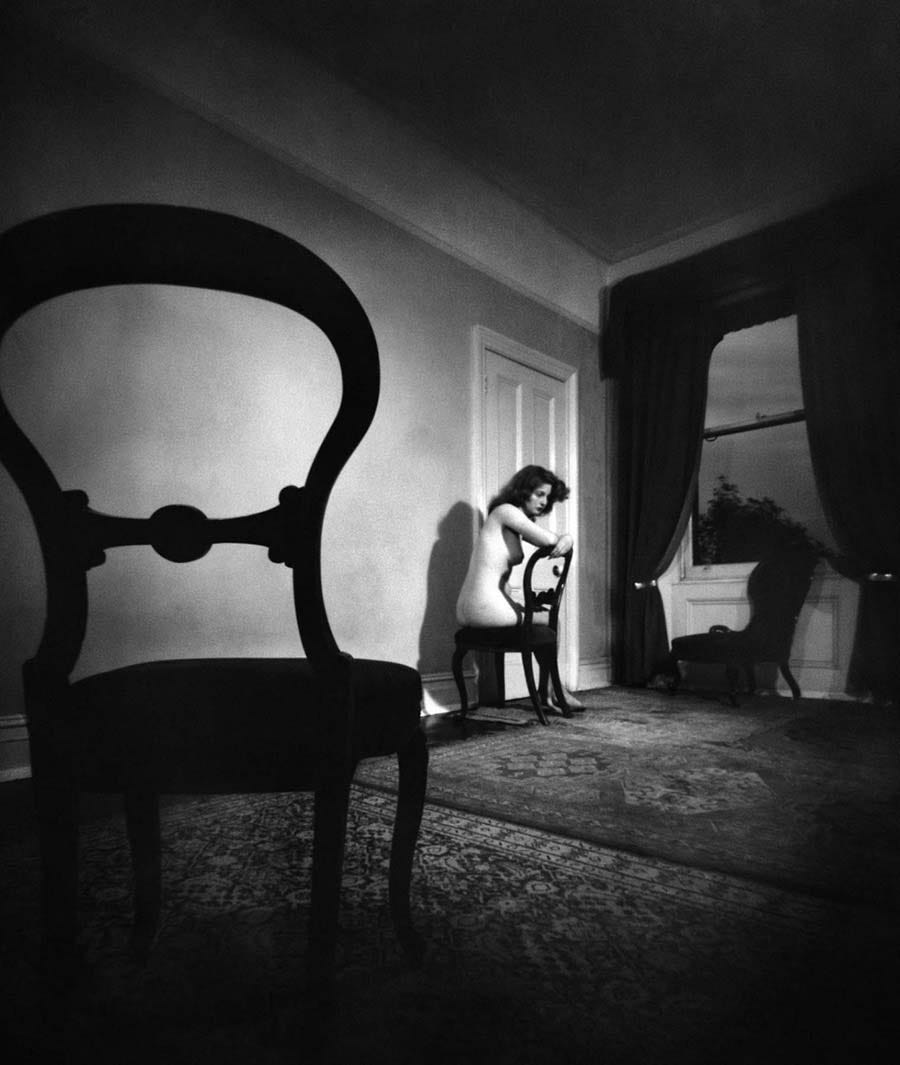

Of Brandt's photographs, Diane Arbus said: "there is the element of actual physical darkness." In the series of nudes made in West London flats, there is an undercurrent of foreboding. The figures are alienated from themselves and the photographer. This is a world of actual sexual relations: complicated and emotional. Everyone is haunted by the post-war uncertainty.

The camera Brandt used was an ancient Kodak with a wide-angle lens that had no view finder. He had to trust his instincts and the camera, leading to some extraordinary perspectives.

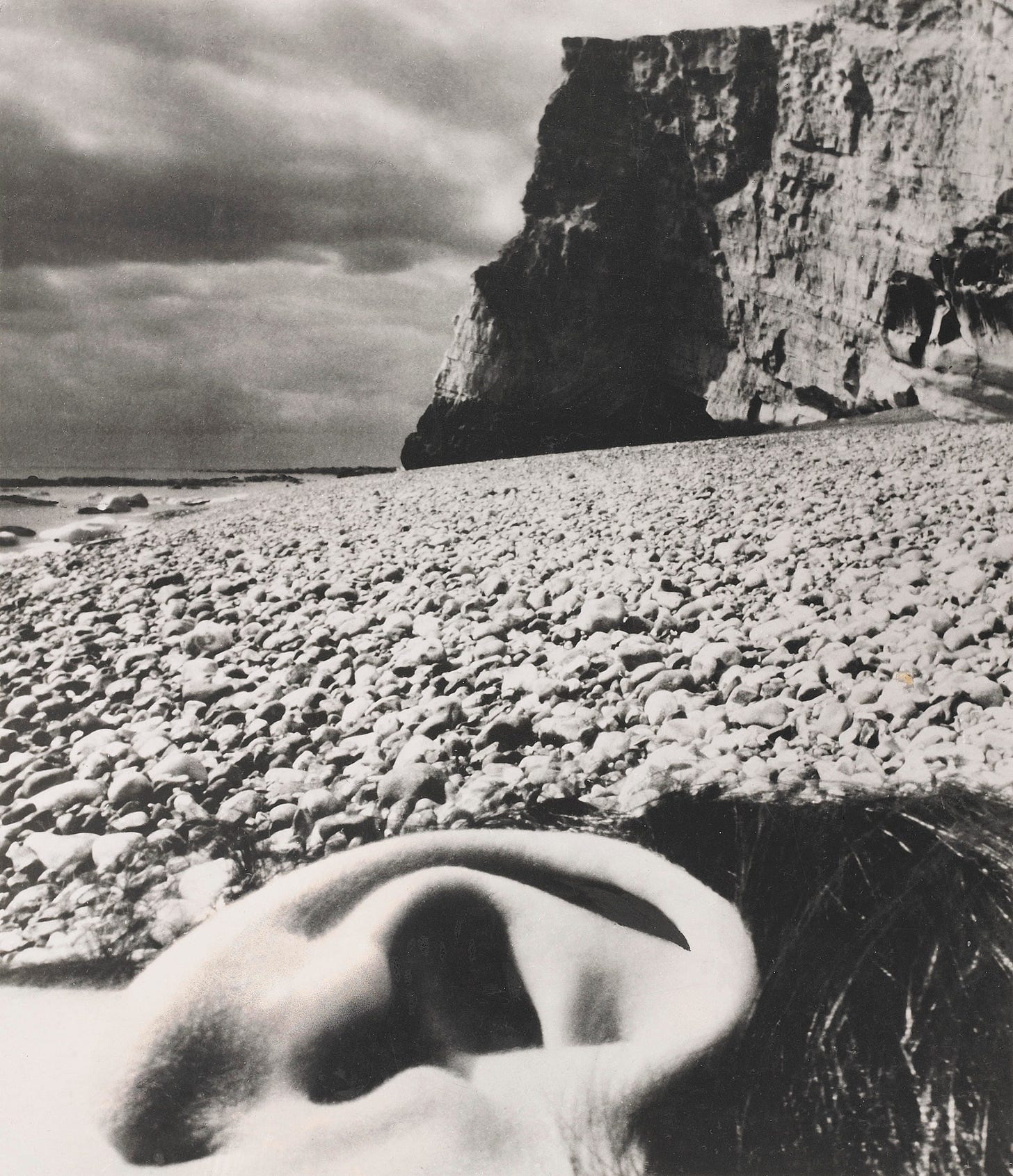

The truly ecstatic photographs come when he visits the beach. Here Brandt's approach to the human body turns every figure into a Henry Moore sculpture. The body becomes a symbol of eternal human forms.

There is an intimacy here that elevates the spirit. We are not dealing with lowest common denominator lizard brain scrolling.

If you want to learn more, I highly recommend Shadows from Light: The Photography of Bill Brandt (1983) by Stephen Dwoskin. It captures a dark, more mysterious artist than the BBC Master Photographers documentary.

The photographs in this article are used for criticism and review under the Fair Dealing provision of UK Copyright Law. All rights to the image remain with the photographer/copyright holder. This use does not claim any rights to the original work and is not for commercial purposes.

Contemporary sex workers are forced to compete with AI models — digital avatars that never get old or need to apply make-up — providing an even more unrealistic body image to women. Through constant iterations, developers hope to land upon the most seductive image possible to sell things to lonely men.

Intriguing comparison. Intriguing write-up. Thank you.

Cheers!