Do you ever feel like a pawn on the chessboard of history?

I do … sometimes literally.

Last week, I took part in a game of human chess.1 I was given a beanie hat with a pawn sewn on top, lined up on the squares with 31 other 'pieces’, and instructed where to move by a curmudgeonly man. It felt oddly liberating to embrace my lack of agency. I could, for half an hour at least, stop fretting over making a bad decision and let others take responsibility.

Even after the game was over, I wondered about how much control we have over our lives. We can’t determine our parents, our nationality, or our genetic make-up. We are also subject to the forces of technological acceleration and global capital. It feels risky to make plans for the future when AI threatens to make many of us unemployed.

We have been here before. In Britain in the 70s and 80s, successive politicians ushered in a deindustrial revolution that led to the closure of coal mines, steelworks, and shipyards, leaving tens of thousands of people out of work and destroying entire communities. While these industries were sometimes inefficient and uncompetitive in a global marketplace, the primary reason to close them was ideological. Margaret Thatcher was clear that she wanted to undermine the unions and create a more individualistic man, saying:

"What's irritated me about the whole direction of politics in the last 30 years is that it's always been towards the collectivist society. […] Economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul."

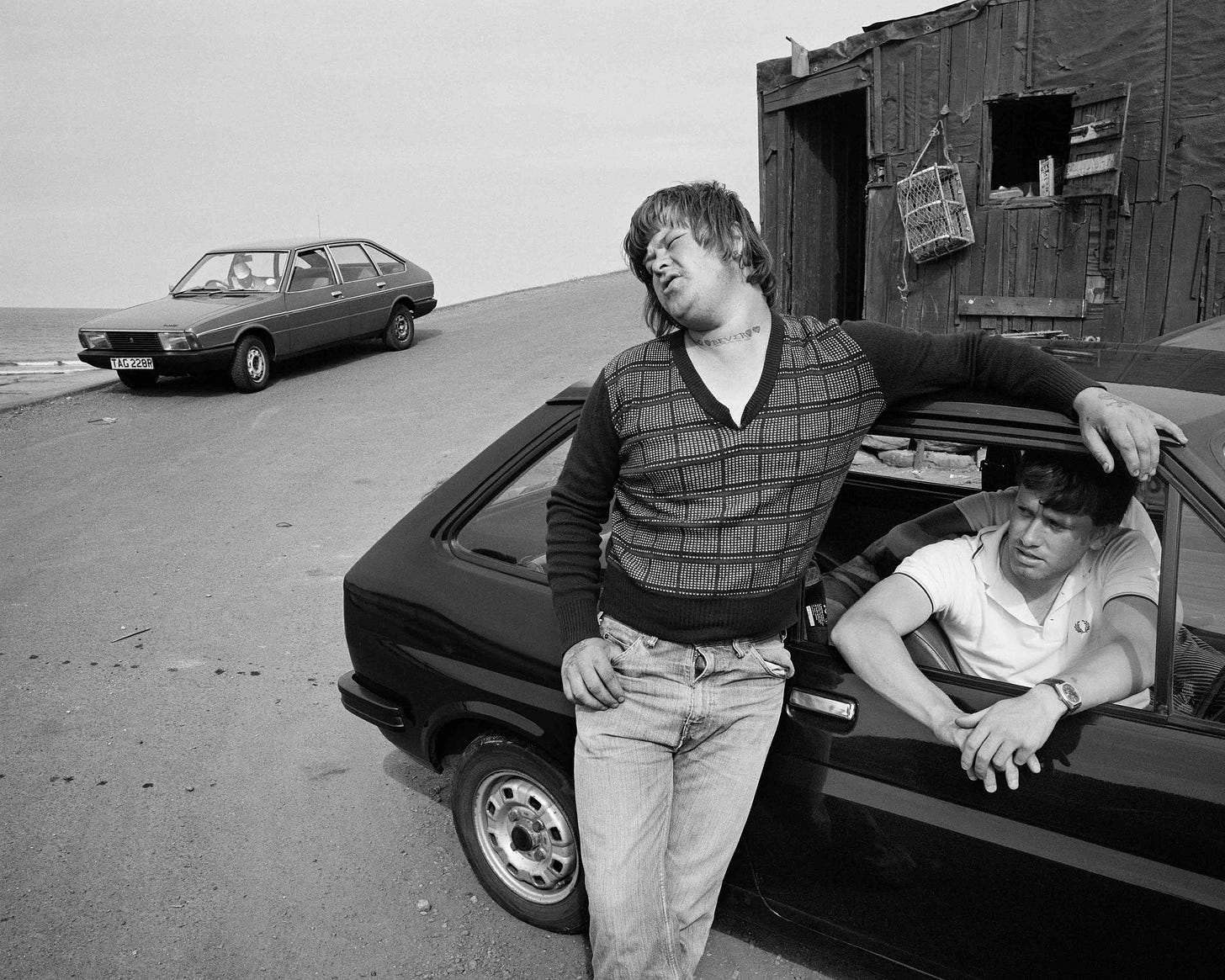

Chris Killip (1946-2020) is the great photographer of the deindustrial revolution and what it did to those people left behind. Originally from the Isle of Man, Killip lived in the North East of England for fifteen years. His friend, Josef Koudelka, told him to “get under the skin of the place and drop his prejudices about what he thought the place should be and to embrace the contradictions of the place.” Killip certainly did that.

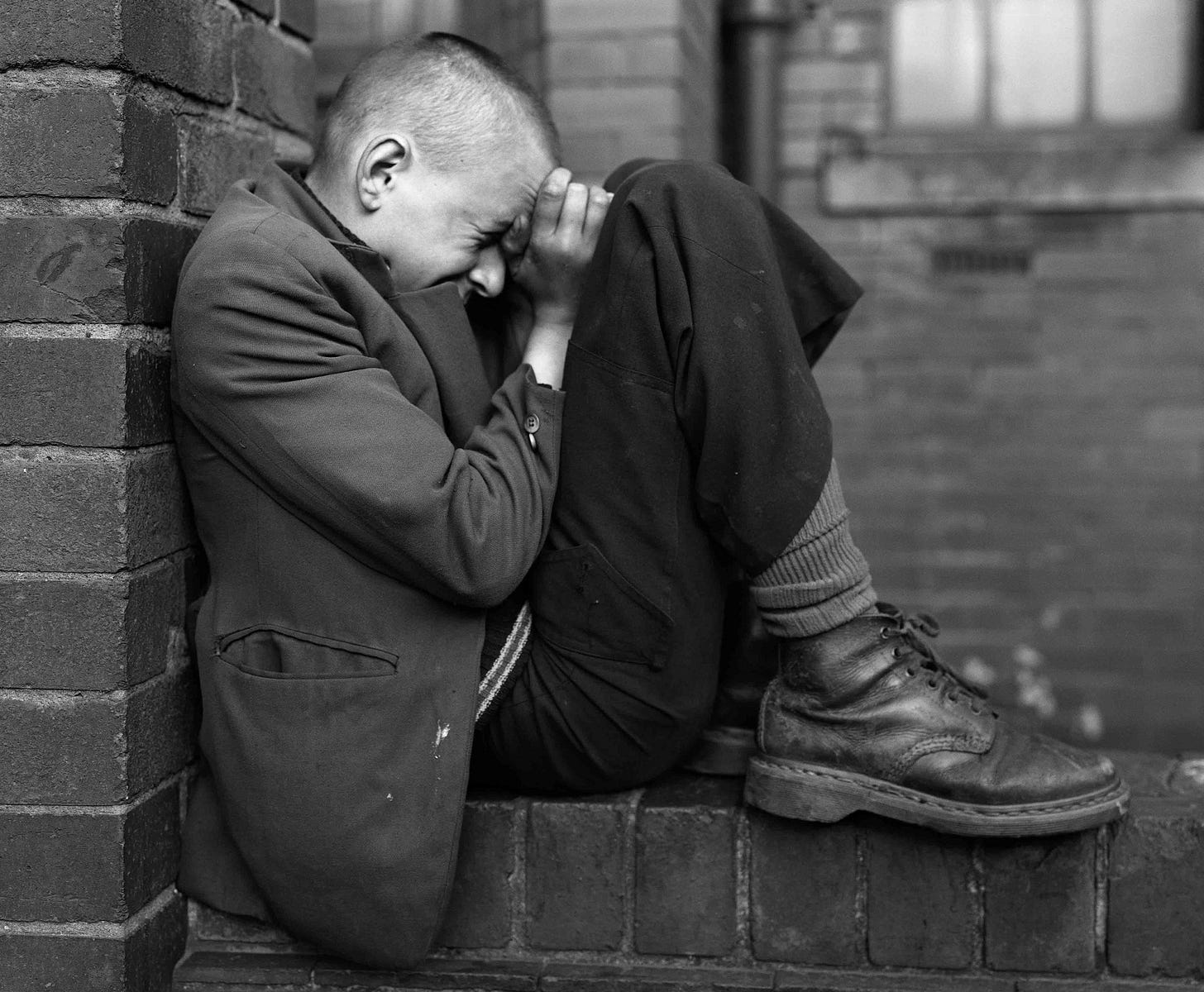

In his classic photobooks, In Flagrante, Skinningrove, and Seacoal, we see a population helpless in the face of economic forces, abandoned. All that remains for them is desolation and despair.

People are dwarfed by huge ships that tower over them like gods, though gods that are about to depart forever.

Killip embedded himself in these places, living nearby in a caravan or otherwise coming back year after year, building the trust required to represent it honestly. The most devastating picture in the recent retrospective at The Baltic was this one of a boy from a fishing community being taken out on a boat for the first time since his father drowned. It’s impossible to imagine this being taken by anyone who hadn’t gained total trust, although Killip himself decided not to publish the image until a couple of years ago for fear of breaching that trust.

He did publish remarkable images of the close-knit community of Lynemouth where people eked out a living gathering sea coal. Killip called it the “Middle Ages and the twentieth century intertwined.”

What makes Killip's images especially affecting is that he often focuses on children, the blameless victims of history. Children, by nature, have to be adaptable to the circumstances they find themselves in. Compare the time-worn face of this father with his false teeth and crossed fingers to the casual arms and quizzical gaze of his son.

Back in 2024, Britain’s decaying cities and ailing economy are reminding some of the 1970s. We have returned to Killip’s North East, except in place of community we have alienated individuals. The direction of our civilization is embodied in things like Apple Vision Pro, which cuts people off from the world to be amused in private.

And yet, despite all this, I can’t quite help but be positive about the future. I follow Antonio Gramsci’s motto of “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” As Silicon Valley booster

says:"Optimism shapes reality, and it sets off a chain reaction. It bounces into people, unleashing their energy and firing their own optimism into the next person to unleash more energy and more optimism.”

What else can we do but reset the chessboard and start another game?

To learn more about Chris Killip, check out the website set up by the Chris Killip Photography Trust and elegantly designed by one of my favourite Substackers,

.The photographs in this article are used for criticism and review under the Fair Dealing provision of UK Copyright Law. All rights to the image remain with the photographer/copyright holder. This use does not claim any rights to the original work and is not for commercial purposes.

The game was organised by Jonny Keen, a sculpture undergrad at the Glasgow School of Art. During the game, he covertly passed written notes to the 'pieces' encouraging them to rebel against their masters. Was he in control? Or was it the tutors who had told the students they needed to do a piece of public art to pass the course? Anyway, what circumstances had to take place for the art world to consider this a worthy academic assignment? Would I be standing on the D5 square, blocked by a black knight, if the First World War hadn't made artists despair at the absurdity of civilization? How far back do you need to go to unravel historical contingencies that have led you to read this post?

Very good summary of one of my favourite photographs, Neil. I love the quotation about optimism too.

And thank you very much for the mention. Working with Chris Killip’s son to design the website was a highlight of 2023. They call it work - surrounding myself with his photo books for inspiration!!

Thanks for this reflection on Killip's work on the North East. My own favourite Killip book is Here Comes Everyone with his photos from the West if Ireland. The setting could not be more different - rural rather than urban, colour as well as black in white, but the same affection for people and their trust in him shines through.