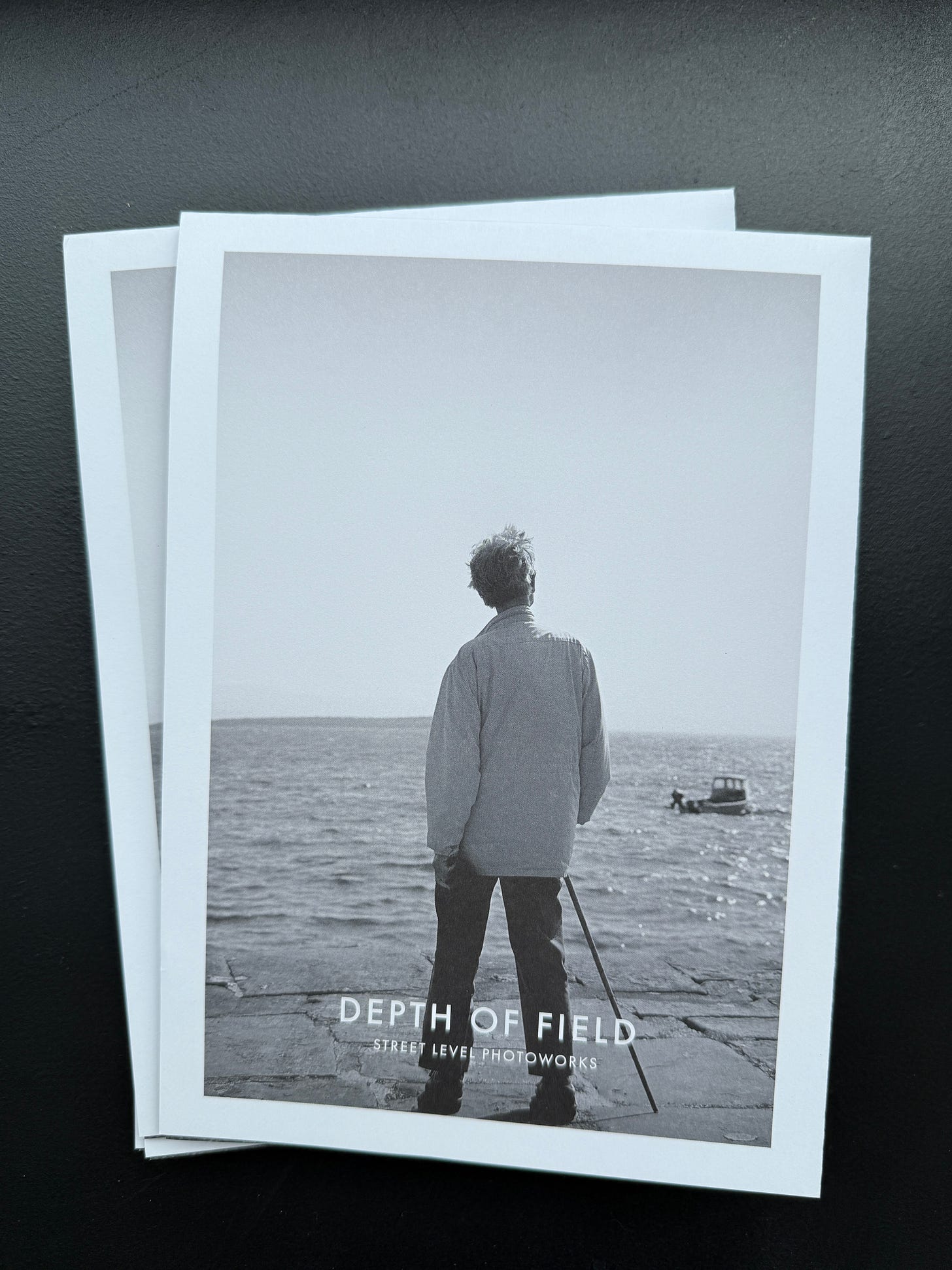

Depth of Field

An essay commissioned by Street Level Photoworks to accompany their exhibition Depth of Field

Depth of Field

f/22

There comes a point in every life when we get obsessed with history. We might be drawn to Orcadian Norse sagas like George Mackay Brown, the remnants of industrial heritage, or even just our family genealogy. Studying the past is a way of reconciling ourselves to our own insignificance: the sobering awareness that, while we will likely be forgotten, some things from our time will endure. But what?

f/16

In photography, depth of field—the f-number—refers to the opening of the camera’s aperture. A large f-number (i.e. a deep depth of field) has a smaller aperture, meaning the entire scene will be in focus. A smaller f-number allows you to focus on a specific object with everything else blurred.

History mostly has a shallow depth of field: it centres on heroic individuals who changed the world. But what of the figures in the background, those who create what Brian Eno called scenius? Eno realised that for genius to emerge it needs to be ‘fed and supported by a vigorous and diffuse cultural scene.’

f/11

In April 1987, Archie McLellan sent a letter to all the other photographers he knew suggesting a meeting where they could show their work and exchange ideas. This led to the formation of the Glasgow Photography Group (GPG), a forum for Independent Photographers whose approach was 'consciously distinct both from traditional amateur styles and from commercial work.'

By January 1988, they had put on a group show in Hillhead Library, with more than 200 people turning out for the preview. Emboldened by this success, the GPG created a photography centre with production and education facilities. This opened in September 1989 as Street Level Photography Gallery and Workshop, helping bring Glasgow up to speed with other major cities that already had dedicated photography spaces, with the added urgency from the fact that Glasgow was due to be the European City of Culture the following year.

What united the GPG scenius wasn't a certain style or philosophy, but a love of the medium and the possibilities inherent in it. As such, there is depth of field in subject matter as well as camera apertures.

f/8

Through the work of Stewart Shaw and Alan Dimmick, we see a city in transition, as it tries to reboot its narrative after the collapse of heavy industry. There is Glasgow’s Miles Better campaign from 1983, which used Mr Happy to try to shake off its reputation for violence. Then there's the 1988 Glasgow Garden Festival, the Tory government's attempt to salve post-industrial alienation.

Glasgow’s population had been over a million in the 1950s, but by 1991 was down to 600,000. Roger Farnham and Sandy Sharp's photographs of dereliction and decay show what is left behind after the forces of history have swept through a place. Perhaps future generations will enjoy these ruins as they do in Sarah Mackay's pictures of Rome, where the crumbling origins of Western civilisation are preserved for tourists.

After all, it’s often only in retrospect that we see the full significance of a photograph. Take the fragments of Ukrainian life captured by Robert Burns, which become ever more poignant after the recent Russian invasion.

f/5.6

While these previous photographers show people as part of the crowd, Leslie Black, David Eustace, and Kay Ritchie give us historic individuals up close. We revere those who made their mark on the age and informed our intellectual journey.

Last year, I learned how Steven Campbell’s transatlantic success inspired a generation of Glasgow-based artists to believe they could achieve international recognition. This year, I discovered that it was Neil Bartlett who invited Derek Jarman up to Glasgow for the National Review of Live Art in 1989. By seeing Campbell and Bartlett in Black's photographs, their contribution to history became more vivid. Such photographs become like relics of the saints.

Before her involvement in the GPG, Kay Ritchie photographed the key writers and thinkers of the era for an early Channel 4 series called ‘Voices’. Salman Rushdie, Stuart Hall, Umberto Eco, Noam Chomsky ... the list goes on. It’s an extraordinary collection of writers and artists, many of whom have become more influential as time goes on. One particularly reflective portrait is of Susan Sontag, whose book On Photography (1977) gave the medium a seriousness that the GPG embodied.

David Eustace had been working as a prison officer at Barlinnie when the GPG began. Photography soon became an all-consuming passion and he rose to fame as a photographer working for glossy magazines like GQ and Vogue. His collection of celebrity portraits was grouped under the title ‘Ego’ when they were exhibited in London in 1997 and give a glimpse of the character of his sitters: Sting is poised and in control, Ewan McGregor curls in on himself self-consciously, and Brian Cox wears the scars of life without shame. We are deeply familiar with his subjects' faces from their films. Photography becomes a way to commune with them one-on-one.

f/2.8

Intimacy is the subject of both Agnes Samuel and Oladélé Bamgboyé. While their aesthetics and techniques are different, they share an introspective quality that is enhanced by being juxtaposed in the gallery. Samuel documents a trip with the painter Bet Low to South Ronaldsay, revealing the affective qualities of the landscape. By contrast, Bamgboyé uses blur and movement in his self-portraits to outwardly express inner feelings.

f/1.4

I love an origin story. There's something liberating about the mixture of instinct and indecision in all beginnings. It is a reminder we can never know the consequences of our actions. We experiment, we learn from the experience. Repeat, repeat, repeat.

So what are the great origin stories? We might think of Spider-Man being bitten by a radioactive spider, King Arthur pulling the sword from the stone, or even Romulus and Remus suckling at the She-Wolf’s teat. A great origin story can be endlessly retold. It provides the spark that inflames the imagination. It’s like DNA: unfathomably small yet somehow containing all the information required to create a living being. At the heart of Depth of Field is the origin story of Street Level Photoworks. With it, we honour the photographers who took a risk and created something new in Glasgow through their love of photography.

The essay was commissioned by Street Level Photoworks to accompany their exhibition, Depth of Field. It was published as a fold-out ‘minigraph’ that was beautifully designed by Alasdair Dimmick. Copies are available to pick up for free—ideally with a donation—in the gallery. The exhibition closed on 28 June 2025.

Thanks for reading! Help support The Crop by sharing it with others or upgrading to a paid subscription.

Snapshots of the exhibition and the accompanying events

Wow. This was pure style. Love the stop-down format that it was written in.

Wonderful essay!