Derek Jarman

A review of "Digging in Another Time: Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature" at The Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow

Last week, I was delighted to be named one of Digital Camera World’s ten photographers you should follow on Substack. Thank you to all those new subscribers who took their advice.

When I began focusing on photography, it quickly became apparent how much easier it is to find an audience when you occupy a niche. The internet is optimised for keywords and algorithms. It demands that we specialise and find our tribe. But I wonder what damage we do in the pursuit of consistency. Maybe we should embrace the contradictions that arise from following our inspiration.

This week, I want to (temporarily) deviate from photography to look at a recent exhibition celebrating the work of Derek Jarman (1942-94), an artist who throughout his career resisted the urge to do one thing.

Jarman was extraordinarily free in his artistic output. Filmmaker, activist, gardener, diarist, poet, painter, sculptor, costume designer, set designer ... he created fascinating work in all sorts of areas without worrying about being legible to the world.

When Adrian Searle reviewed PROTEST!, the 2021 retrospective in Manchester, he pointed out that it's "hard to read [Jarman] coherently.” And that: “Coherence is probably overrated [...] lives aren’t lived that way."

The exhibition at the Hunterian doesn't attempt to address every facet of Jarman's oeuvre. Instead, the curator, Dominic Paterson, has brought together a motley collection of objects and artworks. Yet, somehow, everything coheres.

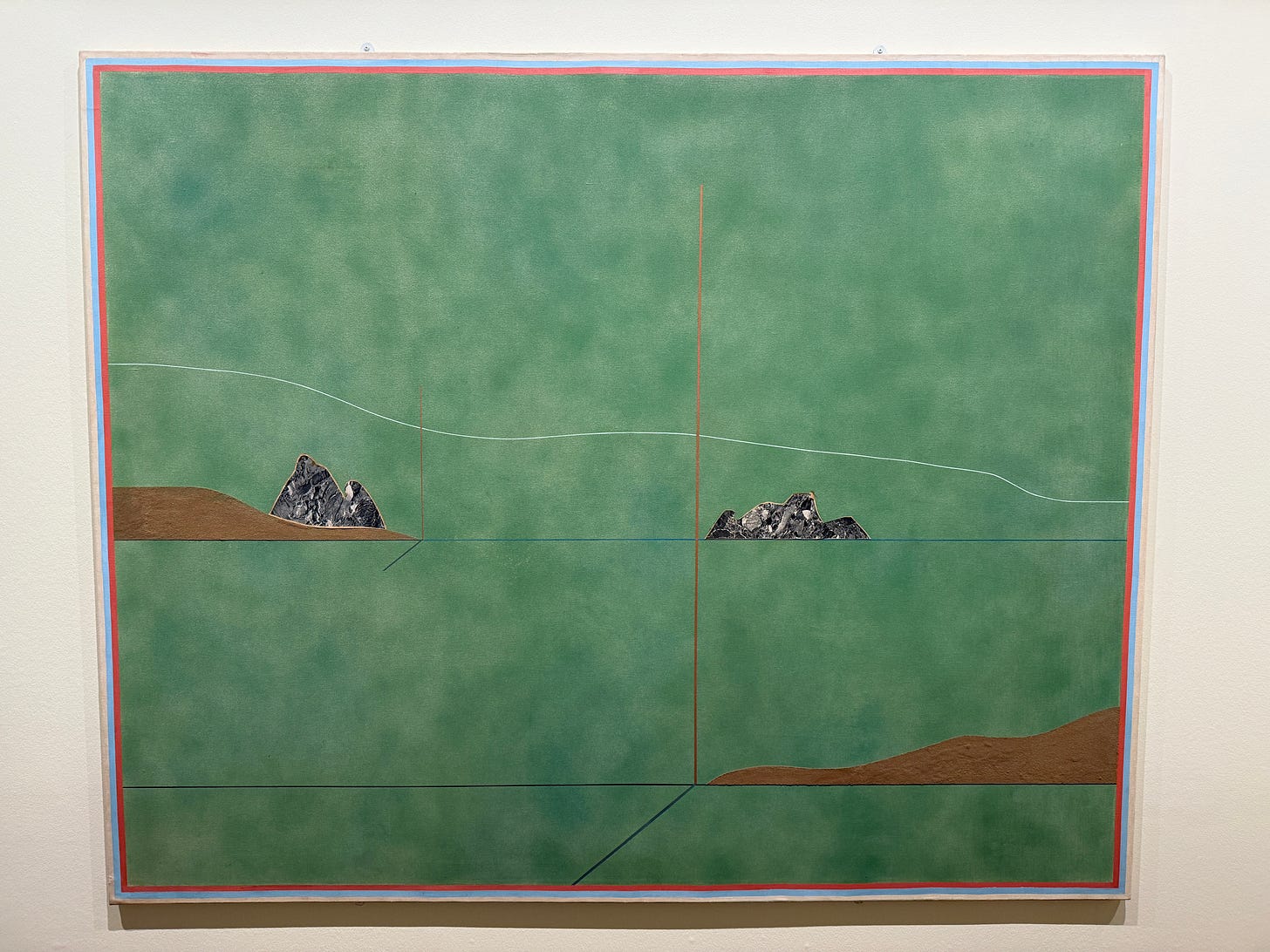

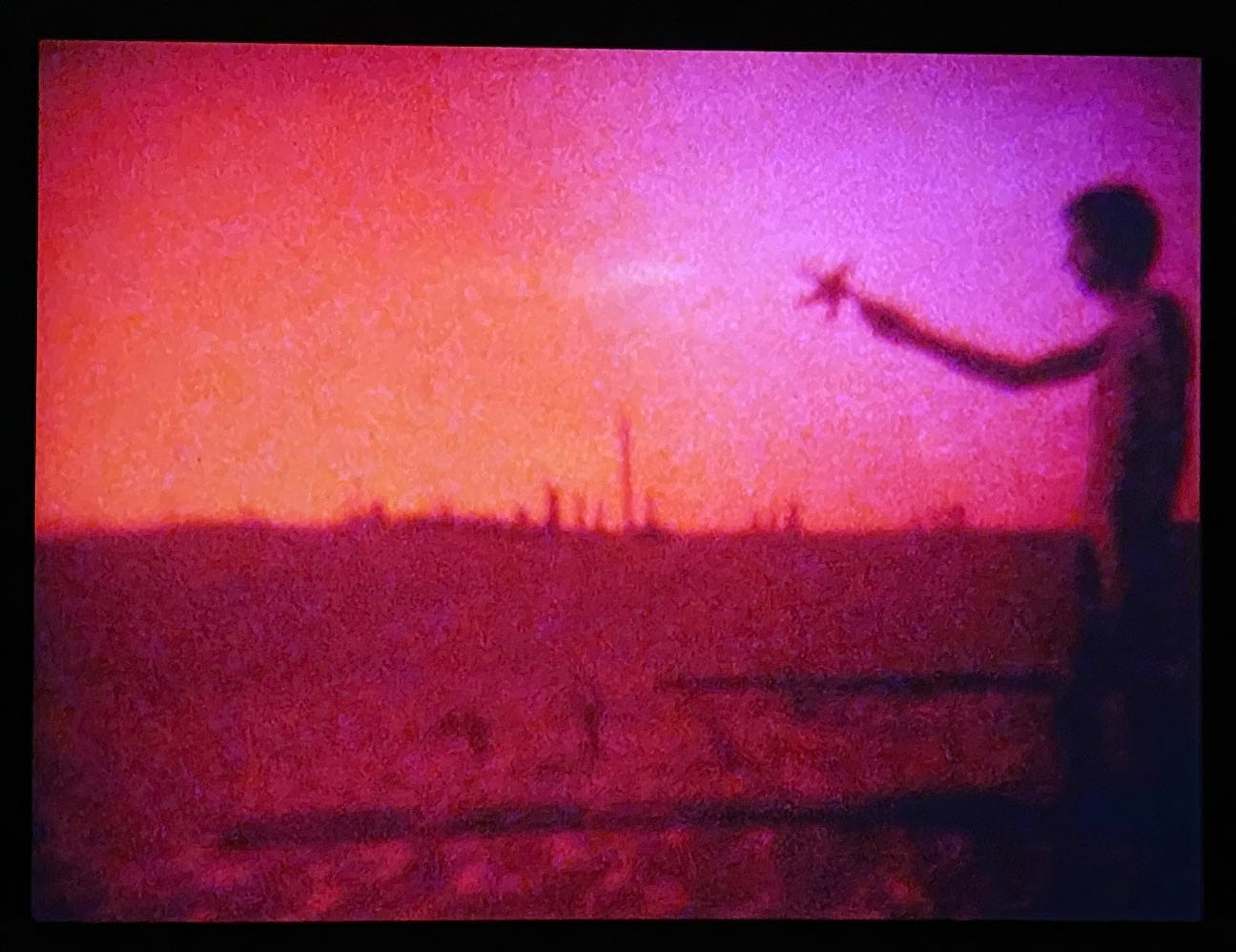

An early landscape painting prefigures the garden at Prospect Cottage (his fisherman's hut on the shingle beach near the Dungeness nuclear power plant). The colour added to the Super 8 short, My Very Beautiful Movie (1974), set on Fire Island, alludes to the colour theories in the experimental feature, Blue (1993).

The show radiates from Modern Nature, the journals he wrote around 1989. This includes the time Jarman came up to Glasgow for an exhibition at the Third Eye Centre. When giving the press a tour of the show, Paterson explained:

There's an amazing catalytic effect that connects him to Glasgow. Suddenly, there's all sorts of fertile, febrile stuff in Jarman’s mind. He's imagining the garden, he's imagining Blue, he's imagining the installation, he's writing it down, he's making these works.

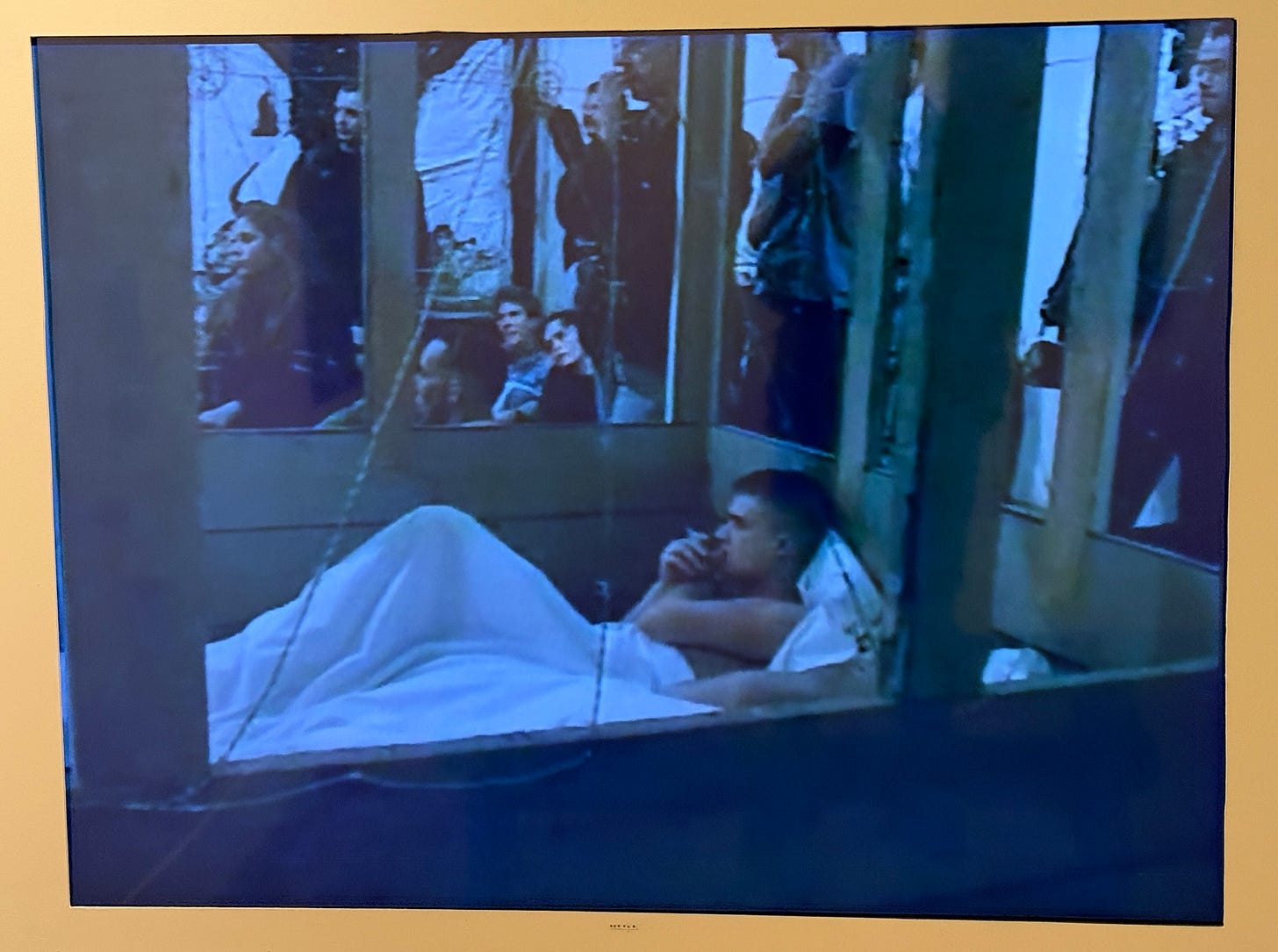

Commissioned in 1989 by Neil Bartlett for the National Review of Live Art, Jarman’s piece consisted of a bed surrounded by barbed wire where a same-sex couple would sleep or lie reading during the gallery's opening hours. Tarred and feathered mattresses covered the walls alongside homophobic tabloid headlines.

My favourite part in Modern Nature is when Jarman imagines what the exhibition in Glasgow will look like:

I spent the day dreaming up the installation for Glasgow: the room turned in my mind from white to black, then blue, then white again. In the centre a tomb/cenotaph, ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’: two young men entwined in Rodin’s Kiss, a shepherd with a staff and drapes from Poussin’s painting. Near the tomb is a bed with two boys asleep – a scarlet counterpane painted with the number 28. There is a virus painting – crucifix, KY and condom – brightly lit.

Jarman worked with intensity. He didn’t attempt to do multiple projects at once. Instead, seems to have worked sequentially, on one thing at a time: a painting in an afternoon, a film in a few weeks, a music video to bring in income.

Now partly this could be that Derek Jarman was an extremely capable person (in our chat, James McKay mentions that Jarman got a double first at King's College). It could also be because he was privileged and could call upon people, like Tilda Swinton, to work for no money. When viewing the paintings, however, all I see is an intense urgency.

Much of the urgency came from his having been diagnosed with HIV in 1986. At the time, this was a death sentence. Then, in 1988, the Tory government introduced Section 28, a piece of legislation that further stigmatised homosexuality by banning any mention of it in education.

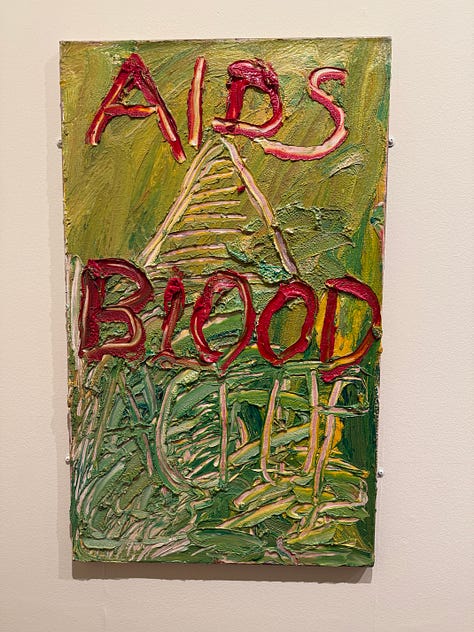

Jarman's series of later “Virus” paintings capture the outrage at the injustice of AIDS and Section 28. Inscribed with headlines from tabloid newspapers or other angry statements, these paintings are ugly but ugly as a protest. Such politically charged, anti-aesthetic art resonates in our era. Although, as Luke Fowler told me, students at the Glasgow School of Art were dismissive.

At the press preview, I asked Dominic Paterson why so many recent exhibitions (e.g. The Ignorant Art School and the Women in Revolt) focused on radical artists from the 70s and 80s. He replied:

There is a sense of rethinking what political art could be, and that's the period of art that is avowedly political and radical. In Dancing Ledge, Jarman says something like “People can only think about us putting our cocks into other people's mouths, but before that we shared ideas.” He's saying that there's [sex], but also there's this creation of new forms of relationship. People want to know how those radical lives were lived: excavating that and trying to understand it.

As Olivia Laing explains in The Garden Against Time although Jarman's garden is seen as a response to his HIV diagnosis, "it also had roots in the childhood needs that had gone so badly unfulfilled."

Tucked away in the furthest corner of the gallery is a film by Sarah Wood that revisits Jarman's childhood in an RAF base. That is where he was given an old botanical book called Beautiful Flowers and How to Grow Them. It was here that Jarman was first exposed to beauty and art. In Wood's film of the same name, she sees it as a question of how to "flourish in a hostile environment."

At the press preview, I got into a conversation with a young journalist who told me that she didn't like culture that wasn't accessible.

"How do you mean?" I asked. "Give me an example?"

"Well, I can't stand Ulysses," she said.

I tried to hide my dismay. That morning I had been trying to get up to speed on Derek Jarman's wild and varied career. When I watch Derek Jarman films I feel invited to converse with centuries of high-brow culture. Wittgenstein, Caravaggio, John Dee: his work is full of signposts for those who choose to investigate.

What's interesting about a garden—and one reason Jarman’s still resonates—is that it is virtually impossible to make an intellectually inaccessible garden. In the metaphorical garden of his work, there are many odd plants and flowers—the diversity of a mind freed from algorithms and keywords. This exhibition highlights the vital things that grew there.

Digging in Another Time: Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature is at Hunterian Art Gallery until 4 May 2025.

Neil,

Congrats on the praise! As you know, I like your work.

I'm not enthusiastic about this review, though. Let me focus on your statement that students were "dismissive." Why? Well, maybe because the story told here, and evidently by the curators runs along these lines:

sensitive/brilliant/different [gay] child

society doesn't understand

young man rebels, is "radical"

young man does great things

society learns

[dark version] young man dies

It's a great story, a very familiar story, in fact the storyline of lots of Disney stuff.

But the story is pretty much independent of art. The great things, in the quotes you give and the outline you tell, are sort of gestured toward (this is "political," this is "radical," so of course he was great?) but not artistically specified. The closest we have is some sort of coherence across media, but what constitutes that coherence?

Rephrased, had Derek been absolutely without talent, just a gay kid trying to make his way in the world, you could pretty much tell the same story.

"Same sex couple in bed" does not automatically make great art. It certainly might be a provocation under certain circumstances, Scotland not that long ago, perhaps, and we might be sympathetic to the provocation, but lots of things are provoking without being art. And the circumstances have changed, so now it's not very provocative, and the kids don't care.

In short, you've situated this work within a transitory politics, which has become worthy but ho hum, not even radical, but you have not really told us much about how the political situation, or the HIV diagnosis, drove a specific artistic statement. So if I were an art student I would say some version of "tell me something I don't know." It might be there, but you've not really said it.

Anyway, delayed flights, I am probably grumpy. Keep up the good work.

Derek Jarmen is a fabulous person when I saw him at third eye centre in Glasgow. His work is breathing taking... and great artists for his film work. Appreciate your article posted. Keep it up...