Graciela Iturbide

On degrowth and other pests

New ideas are like pests. Most are like flies: we swat them away and never think about them again. Some are like mice: they nibble away and force you to take decisive action when you notice their droppings. It's rare to have a wolf-like idea: one that is initially dangerous but can, over time, be brought into the home to become a loyal companion. Which type of pest is the idea of degrowth?

Until recently, I was only aware of degrowth in the vaguest way. I skimmed a review in the LRB that mentioned it. I half-listened to the episode of Under the Skin with Jason Hickel. I was aware that the Centre for Human Ecology was associated with a degrowth magazine called Enough, but never got around to reading it. A member of my book group suggested reading Kohei Saito but that hasn’t happened yet. Degrowth was a fly buzzing on the other side of the room.

The mouse stage—when it became unignorable—occurred last summer. In July, I read Sam Bowman's piece on the sorry state of the British economy. Bowman is a YIMBY who wants to build houses and infrastructure. He linked to an attack on degrowth, which was interesting but didn’t really engage with any of the key thinkers behind the movement. It's easy to denounce something by strawmanning. Later that summer, after visiting Bene Bergado’s Degrow exhibition in Bilbao, which presented a toxic post-apocalyptic vision of the future, I resolved to investigate.

I read Giorgos Kallis and learned that the French environmentalists have been discussing Degrowth (Décroissance) since the 1970s. The idea has been lately popularised by Extinction Rebellion, for whom it is something of a guiding principle. My initial reaction was that degrowth is a terrible name for an environmental movement.1 Growth is good, growth is life. Why would you want to be anti-life?2

Fortunately, Jason Hickel, whose book Less is More was my main reference, is here to clarify:

“[Degrowth] is not about limits but interconnectedness—recovering a radical intimacy with other beings. It is not about puritanism but pleasure, conviviality and fun. And it is not about meagreness but bigness—expanding the boundaries of human community, expanding the boundaries of our language, expanding the boundaries of our consciousness. It’s not just our economics that needs to change. We need to change the way we see the world, and our place within it.”

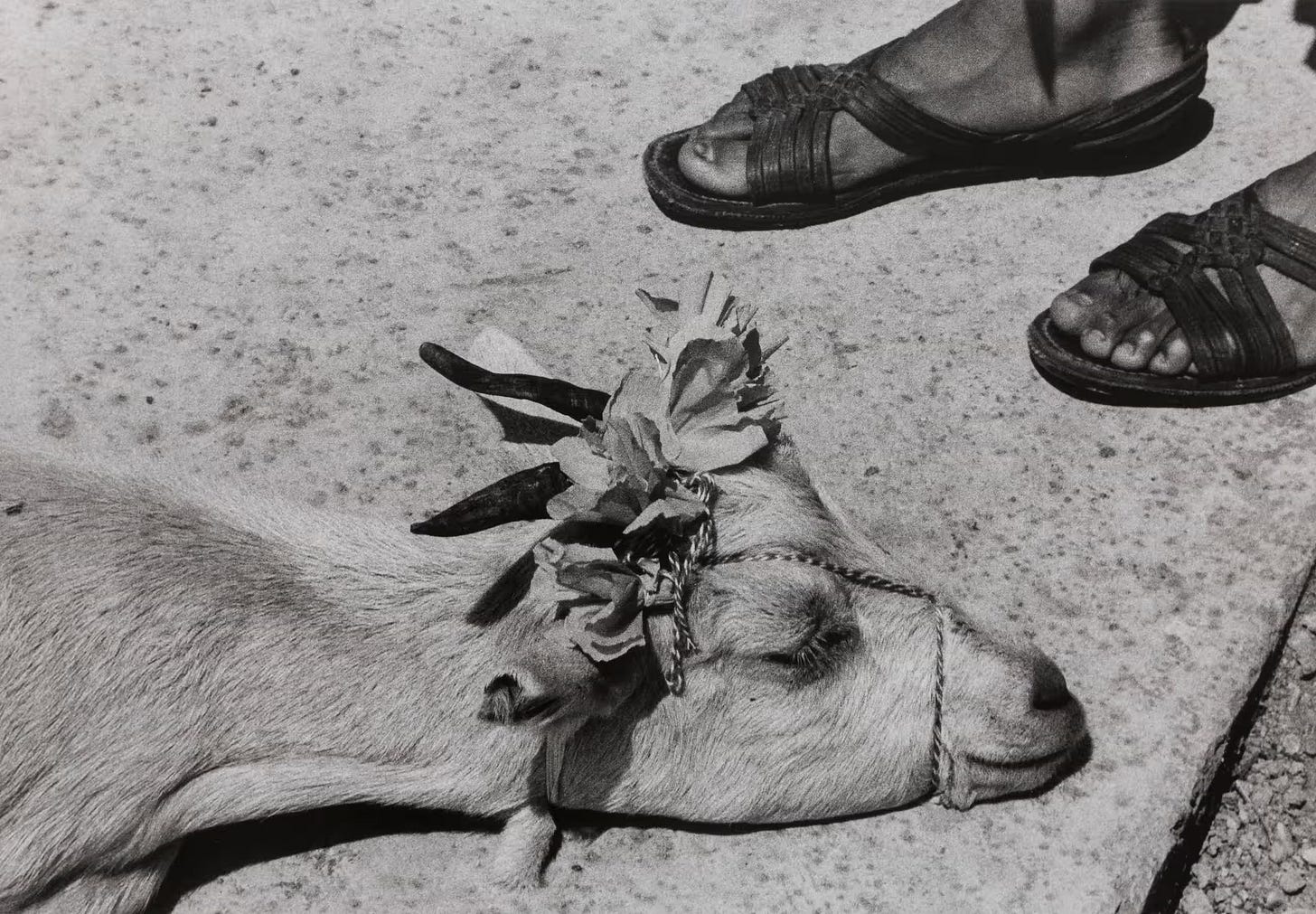

Hickel talks about kinship and animism, decolonisation and enclosure, showing how “nothing exists alone. Individuality is an illusion. Life on this planet is an interwoven mesh of relational becoming.”3 I was reminded of this line when I looked at the photographs of Graciela Iturbide (b.1942).

Iturbide is a Mexican photographer best known for her long-term documentary of the indigenous people of Juchitán, a place she has been visiting since 1979. This is a rare society where women are in control and transwomen are embraced. As such, it offers an insight into the potential diversity of human arrangements, the subject of Graeber and Wengrow’s recent book Dawn of Everything. Iturbide is not a native, but she never turns these people into an exotic other. Her photos have a quiet dignity, showing the people closely interwoven with the plants and animals that surround them.

As Iturbide said in an interview with Frieze:

“It’s essential that my subjects trust me, that there is complicity. I often live side by side with them for long periods. I never take photos in secret and I’ve never used a telephoto lens. My subjects always know I’m there as a photographer and, if I feel someone doesn’t want their picture taken, then I don’t take it.”

This relationship with her subjects is mirrored by the relationship of the Zapotecs with their animals. They represent an existence before life has become completely alienated from nature. If we are to avoid a sixth mass extinction we must stop destroying ecosystems and accept our interconnectedness.

As a political programme, degrowth faces immense challenges but the idea is worth discussing and photographing, even if you initially want to swat it away.

The photographs in this article are used for criticism and review under the Fair Dealing provision of UK Copyright Law. All rights to the image remain with the photographer/copyright holder. This use does not claim any rights to the original work and is not for commercial purposes.

I’m told that the word sounds less odd in French. Décroissance was coined in the 1970s by André Gorz who, to the delight of people who say "Well, if you think the population should be reduced, why don't you start with yourself?” did sadly kill himself.

It is worth noting that plants and animals don’t grow at 3% forever. Growth without limits is literally cancer.

The main difficulty for degrowth will be selling the idea to the electorate, who are unlikely to vote for anything that sounds like it will make quality of life worse. There’s a good debate between Hickel and Sam Fankhauser, a Green Growth activist, that addresses this.

Interesting thoughts and photos Neil. I know little about degrowth (or Graciela Iturbode), but I do feel we all need to reduce our consumption if we are to sort the world’s climate problems. Net zero is not enough (and, along with sustainability, has been coined by too many marketing departments to sell more stuff).

A book I picked up from my mum’s shelves recently is ‘Small is Beautiful’ by E F Schumacher. She wrote lots of interesting notes in it. I plan to read it next.

Anyone near London can see her work at the Photographer's Gallery right now, worth a visit indeed