What I want in life is to be fully intentional while having maximum opportunities for serendipity. I want to plan my days so that they are filled with things I could never have planned. This may sound like a paradox. Like having one’s cake and eating it. But it can be achieved if you go for a walk with a vague destination in mind and enough time to make detours.

Last weekend, we were in London for the Idler Festival and had a day free to wander the city. There was nothing I desperately wanted to see, so we thought it would be interesting to drift into town.

One vague, London-based desire I had was to pick up a copy of The Toe Rag magazine, which this quarter has an article on Sophie Calle. Every twenty minutes or so, I would check on their website to see if we were near a stockist. On one such occasion, I noticed that we were close to Victoria Miro gallery and decided to pop in.

Alas, there were no magazines, but we stuck around to see their 40th birthday group show, where each artist on the roster contributed one piece. It was fascinating to spot how many were recognisable at a glance, such as Chris Ofili's instantly identifiable Afro-pontillist canvas.

It seems all great artists need a signature style of their own. Mondrian, Pollock, Seurat, Modigliani—we know them a mile off. For these artists, their technique becomes a world view. You only need to see one or two examples of their work for it to become an indelible memory.

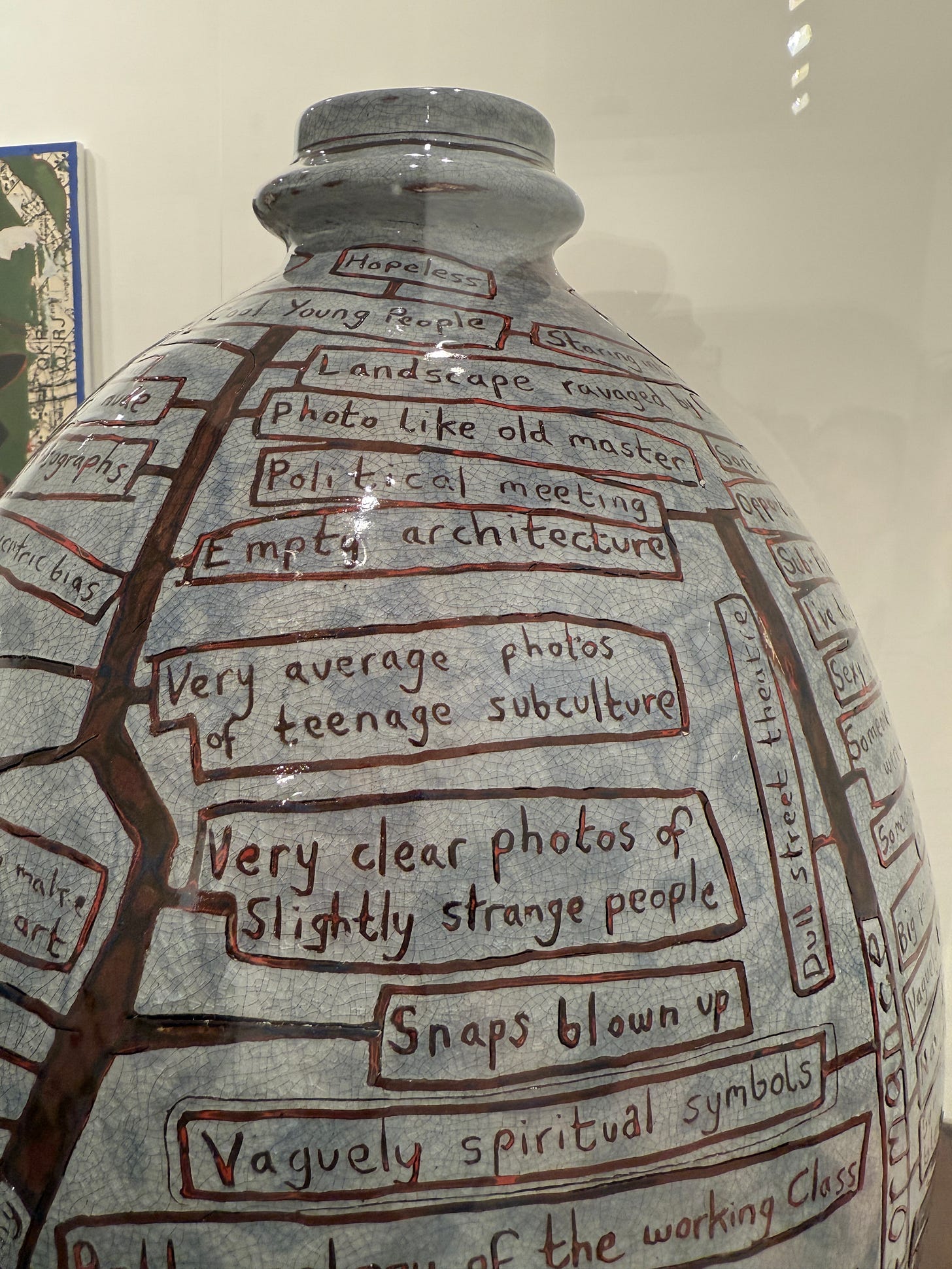

Grayson Perry is not an accomplished artist in the traditional sense. His drawn figures are scratchy, naive cartoons. Nevertheless, he has carved a place at the heart of English culture through pottery and tapestry—forms which are otherwise neglected in the world of fine art.

For this exhibition, Perry presented a new pot titled Forty Years of Art Trends in a Palatable Form, which lists the recent follies of the art world. Now that he is a kind of national treasure, safely ensconced in the TV schedules, Perry can be critical without worrying about being blacklisted. And so, there are no drawings, no colour, just a collection of themes that he has noticed. I was particularly struck by what he identified as"Very Significant Photography". Here they are decoupled from his design:

Very clear photos of slightly strange people

Very average photos of teenage subculture

Snaps blown up

Empty architecture

Photo like old master

Landscape ravaged by climate change

Cool Young People staring into the distance

Hopeless

I'm foreign me!

Social work

Anthropology of the working class

Grungy fashion shoot

Cardboard Reality

Brave immigrants

HUGE photographs

Dysfunctional family album

Aging punk coolness

Spooky/sexy

Prints on aluminium

Blurry

Semi-pornography

Negative image

Life imitating art

I've just discovered Identity

Person ‘interacting’ with the landscape

Good looking girls being ‘meaningful’

Small things close up

Staged scenes

On seeing this list, it is tempting to try to guess which famous photographers fit each description: Wolfgang Tillmans, Edward Burtynsky, Ryan McGinley, Andreas Gursky, Gregory Crewdson, Thomas Demand, Richard Billingham, Francesca Woodman … they're all there. But what Perry is really describing is cliché: things that he has observed in the gallery again and again, work that is so generic that it doesn't need to be associated with a specific artist.

Of all the art forms, photography seems like it should be the easiest to imitate. But is it? I have been accused of imitating Martin Parr—and it's true that I love colour and human folly—but I don't use flash and rarely get as close as he does. Even if I went all-out to copy him, I don't think it would work.

As Parr says:

I like photography because people think it’s easy, but in fact, it’s just as hard, if not harder, than any other medium. It appears to be very easy because all you have to do is pick up a camera and you don’t need any technical knowledge anymore; a camera does it all for you, and you click away. All you see is lazy photography everywhere.

Grayson Perry is a big fan of Parr and is effusive about his work in the I Am Martin Parr documentary. Yet Perry's own experiments with photography have been less successful. His photos from 2007 are not just bad but boring.

In 2013, Perry announced that, since the advent of digital photography, he had stopped taking photos for fun:

I don’t know whether this is because of age, laziness or the feeling that photography has become a torrent of cliches. The cameraphone has made the forest of glowing screens ubiquitous at events. Maybe I’m a snob, but it’s put me off photography.

In his blockbuster exhibitions, Grayson Perry makes a virtue of his limitations and enthrals crowds with pots, tapestries and maps. These days, his cultural status looms so large that he can go on a national tour about how to tell if you're good. Perhaps goodness is a subject that has been on his mind because he is becoming increasingly reactionary. What he has produced is a kind of sarcastic, ceramic complement to Dean Kissick's The Painted Protest essay.

When I posted the photos as a note,

assumed that Perry was being cynical. Maybe so, but Perry’s critique is a pointed provocation. In a world of abundant ‘content’, it is easy for everything to blend into one. It’s only by occupying a niche that we can make any visual impact at all.Just as I want to rigidly plan my days for maximum randomness, the dream of the artist is to have a trademark style that doesn't constrain the work. The substance should be as capacious as the universe, but the vessel is ours alone. Ultimately, that means saying no to virtually everything but what is yours.1

Post Script

As I was preparing this post, I saw that

and had conducted a fascinating dialogue about whether style constrains their work. Both photographers prefer to follow their instincts rather than prejudge the outcome. I understand and do much the same myself. Yet, we can’t communicate with others unless we know what we want to say; that, surely, means ruthless selection.For a contrary view, I recommend

’s post—Is Style Important?—from a couple of weeks ago.This is also why many of us are obsessed with originality. Those are the people who help define the cliché. They should be acknowledged as pioneers. However good your photos are, they lose all resonance in the eyes of connoisseurs if they are derivative.

hold on a second: did you get the magazine? 😁

Hi Neil, this is a really fascinating topic! I agree that at times we have to take contradictory stances in order to survive the tension of growth versus opportunity. You said that in order to communicate with others, it requires ruthless selection. I embrace a more postmodernism stance, but I’m certainly not going to impose that on anyone else. I believe that to be ruthless about anything is to inhibit and constrain, and when I inhibit or constrain anything, I’m not giving room to alternate possibilities. That is just me and what works for me and what has allowed me to grow. In the past, my approaches were 1000 times more stringent, calculated and precise. I feel strongly though, that that this kept me back from both enjoyment and growth. Today, I’m enjoying myself way more than ever in all my art forms. My goals are simply to enjoy and learn. I no longer long to be anything specific. Again, different strokes for different folks. By the way, I’m very interested in looking more into Perry‘s work. I’m a huge fan of Martin Parr as well! Thank you for the provoking thoughts.