Helmut Newton

Intuition and the power of fantasy

We were sitting by the side of the pool, as the swimmers did their laps, and I asked F. how his novel was coming along.

“It’s not,” he replied. “I’d like to write a book, but I don’t have anything to say.”

I raised an eyebrow.

“Seriously, I’ve looked inside myself and there’s nothing there.”

Typical Glaswegian self-deprecation, I thought. But he insisted it was true.

“I’m not sure that’s how creativity works,” I told him, recalling the time I saw David Lynch at the GFT in 2008.

Lynch had been on a book tour and talked about how transcendental meditation allowed him to dive below the conscious mind to find what he called the “big fish.” As Lynch writes:

Through meditation one realizes the unbounded. […] Life is filled with abstractions and the only way we make heads or tails of it is through intuition.

The great thing about using David Lynch as an example is that however trite the advice, they can’t argue with his back catalogue. Blue Velvet and Mulholland Drive are classics. Eraserhead and Elephant Man are strangely brilliant. Even his misses (Dune, Inland Empire) are worth reflecting upon. In Lynch’s work the guardrails of the conscious mind have been removed and the unconscious seeps into view.

Art cannot be created intellectually. The artist is a vessel, channelling the sensory inputs of a lifetime. The less they force ideas, the more powerful and multifaceted the work.

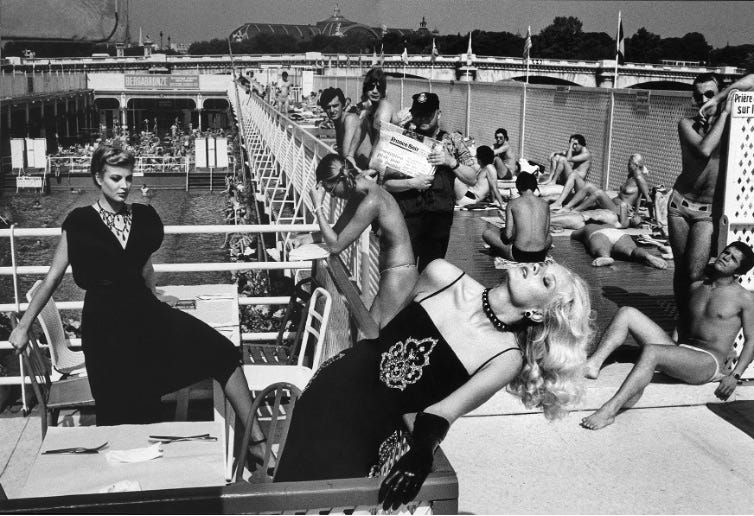

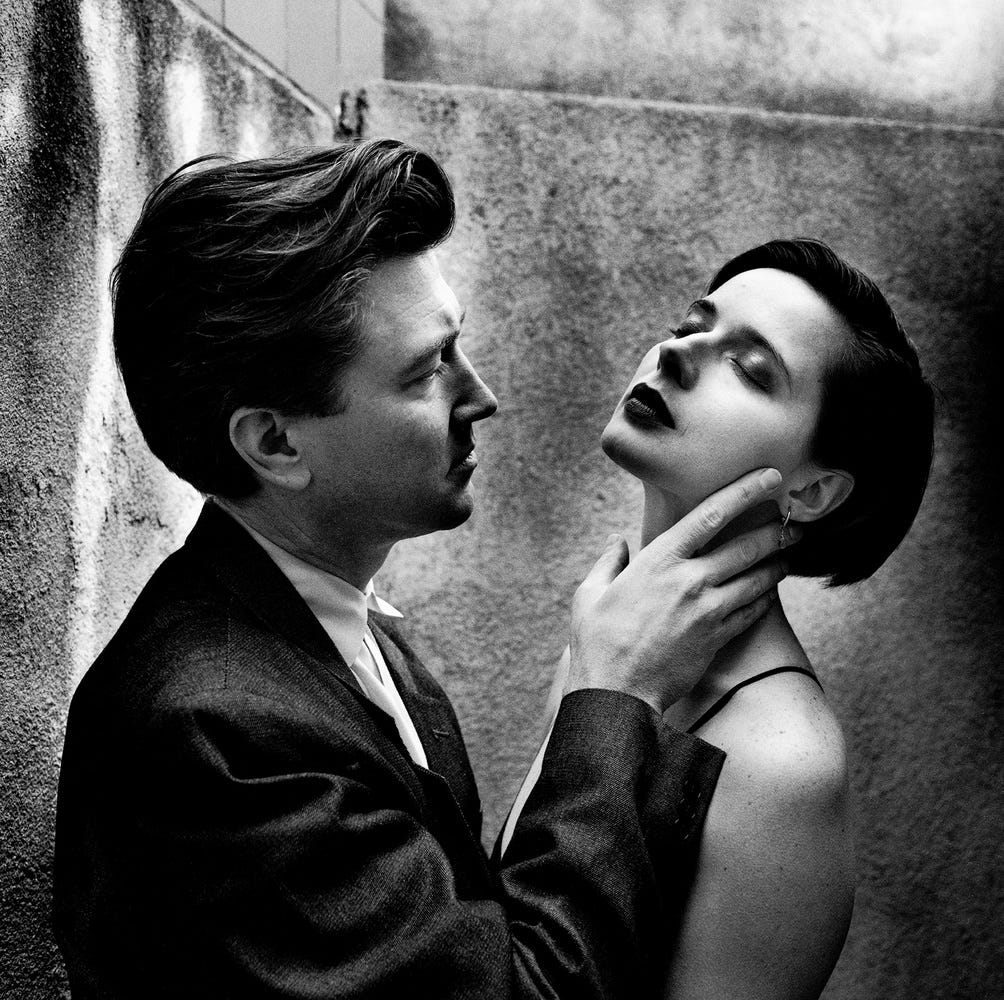

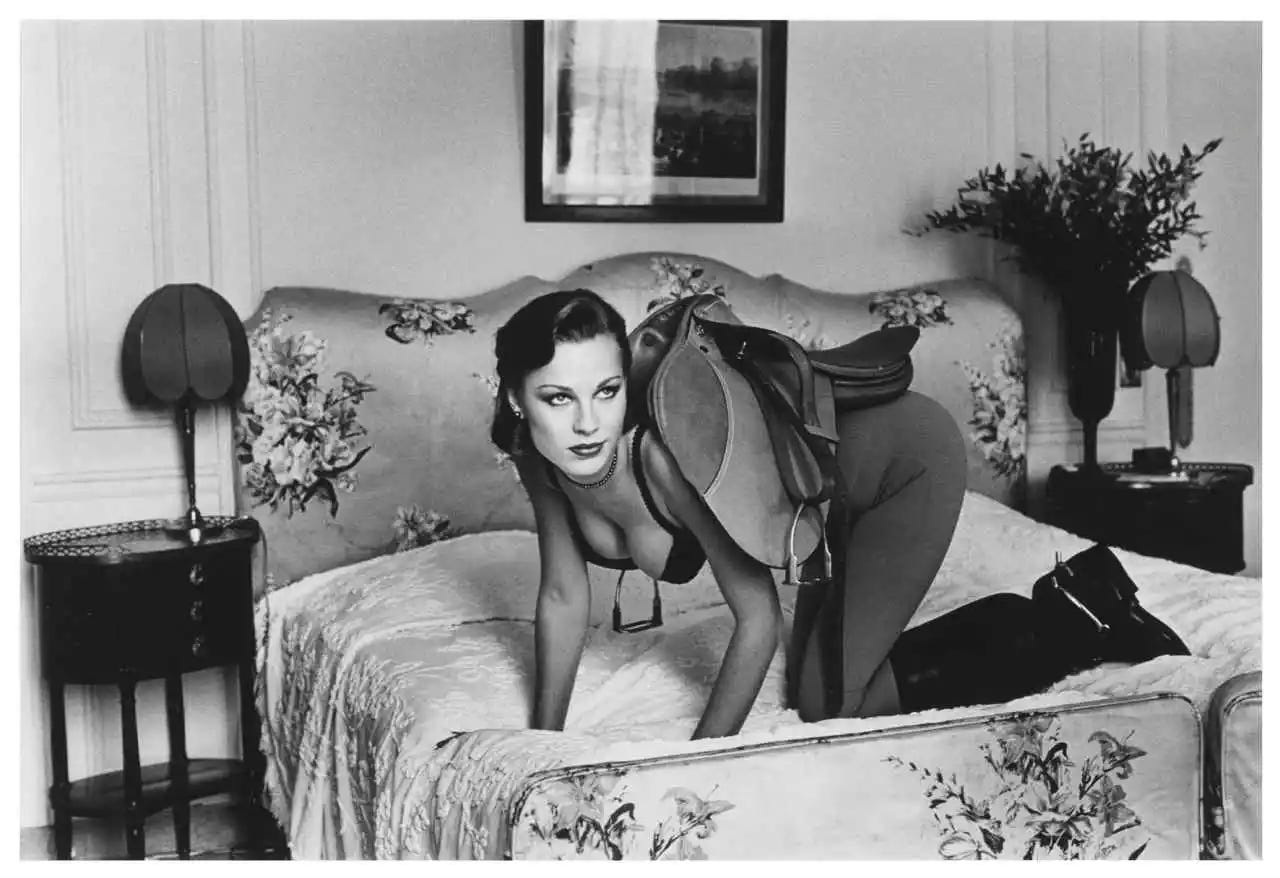

Helmut Newton is a photographer who allows the unconscious to run loose. His scenes don’t make rational sense but the dream logic adds up to something memorable.

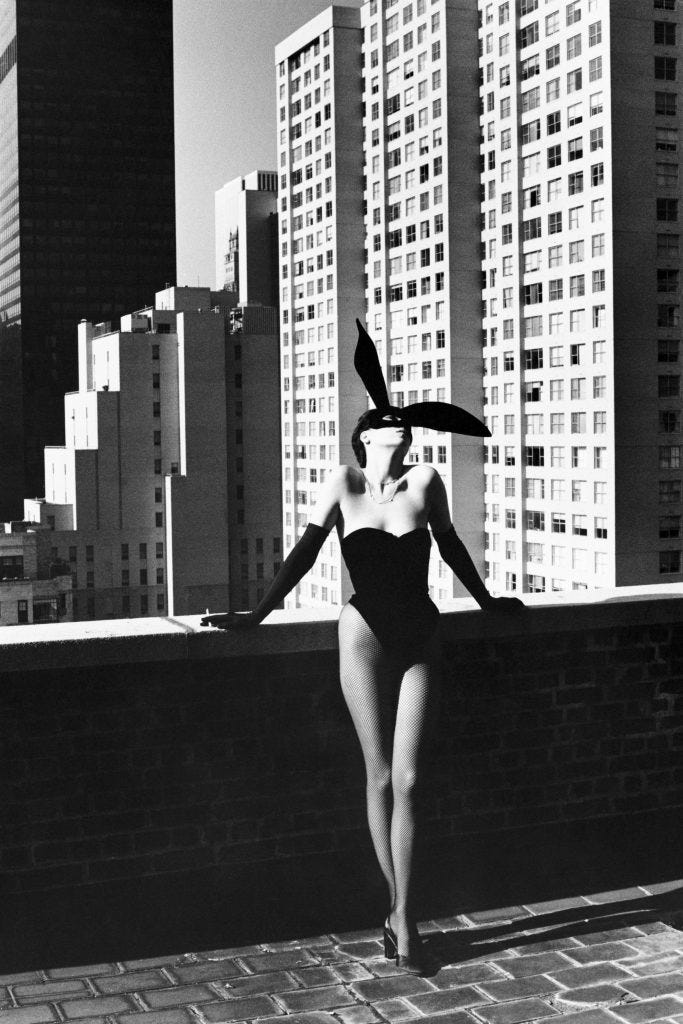

Newton is mainly known for his daring photographs of dominant women, which became a cultural archetype in the eighties. Although shocking at the time, in our porn-wearied culture they now look tastefully erotic. The origin of these perverse images is usually ascribed to his upbringing in Weimar Berlin.

Born in 1920, Newton had an older brother who initiated him into the decadent sexuality of the era, showing him some of the notorious prostitutes when he was barely in his teens. But it was the images of physical grace in the work of Hitler's favourite filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl, that left a lasting aesthetic influence.

At 16, he was apprenticed to the fashion photographer Yva. Like Yva, Newton came from a Jewish family. Unlike her, he managed to escape the holocaust, ending up in Australia, where he met his wife and muse June Browne (aka Alice Springs).

Newton's early fashion photography is conventional and rarely features in books about him. It was only after he suffered a heart attack in 1971, aged 50, that he started the work for which he is best known.

A glimpse of mortality reminds you of what is important. You give up illusions of vanity and you stop caring about propriety. As if to emphasise the new era, Newton took his camera into the hospital and photographed himself naked. Later he said:

My photos are stamped with vulgarity! Creation comes from bad taste and vulgarity. Good taste is anti-fashion, anti-photo, anti-female, and anti-erotic! Vulgarity is life, amusement, desire, extreme reactions!1

The recent film about Newton, The Bad and the Beautiful, is full of actresses and models praising him. The purpose seems to be to innoculate him, in the #metoo era, against accusations that he objectified women. But it's not difficult to see why many women desperately wanted to work with him: the images are incredibly seductive, full of power and freedom.

Susan Sontag wrote that "photography is the only art that is natively surreal."2 Whereas Surrealist painting was a "meagerly stocked dream world." By following his intuitions Newton created, in the words of J.G. Ballard, an "extremely sophisticated and highly ambiguous" universe. Like Ballard, Newton works with an impenetrable core of disturbing memories. He doesn't disavow these memories but shapes them into archetypal forms and fantasies.

When you see Newton at work he seems untroubled by doubt and introspection. With his awareness of desire and mortality, there is an easeful simplicity to everything he does. So, F., don't overthink. Follow your creative intuitions and see where they lead.

The photographs in this article are used for criticism and review under the Fair Dealing provision of UK Copyright Law. All rights to the image remain with the photographer/copyright holder. This use does not claim any rights to the original work and is not for commercial purposes.

From 1976 April/May issue of Penthouse Photo World

In On Photography. Sontag also notoriously called Newton a misogynist on French TV.

Amazing photography.

I immediately read about him on Wiki …. traumatic early life and interesting later life.

I've never been sure what to make of Newton. As you suggest, he's probably best viewed as a product of his time.

I sympathise with your friend F. 'I don't have anything to say' seems a reasonable response to a world where it seems everyone believes they have something to say, and proceed to say it an increasingly shrill and aggressive manner.