Reviewed:

Met Gala Ball (2024)

Coca-Cola advert (2025)

'Myths of the New Future' at The Common Guild (until 12 July 2025)

Met Gala Ballard

The 2024 Met Gala Ball was, by all accounts, a disappointment. Its theme was JG Ballard’s The Garden of Time, a short story about a pair of aristocrats who delay an invading mob by plucking magical roses. Presumably whoever chose the theme was satirising celebrity vanity in the face of catastrophe, but that didn’t really register: the dresses were dull.1

The most Ballardian2 line in The Garden of Time is when the protagonist sees the “approaching horde” reach the garden:

As far as Axel could tell, not a single member of the throng was aware of its overall direction. Rather, each one blindly moved forward across the ground directly below the heels of the person in front of him, and the only unity was that of the cumulative compass.

This is what Ballard represents—blind, purposeless inevitability. With Ballard, the catastrophe has already happened and we are waiting to see it play out.

“It’s the real thing”

A couple of weeks ago, Coca-Cola released a series of adverts showing the times that great writers had mentioned the iconic fizzy drink. With Ballard, they misquoted a Paris Review interview and gave the book the title Extreme Metaphors which is the name of a 2012 collection of Ballard’s interviews edited by

and Dan O’Hara.Apparently, the creative agency, VML, employed AI to generate the quote and the book. Suddenly, this banal advert became a foretaste of the future3 where facts are hallucinated by AI and no one cares to check if any of it is true.

Ironically, 13 years previously, Dan O’Hara (along with

) had provided the research for the company that created an infomorph of on Twitter. Ronson was unhappy about this, took them to task (see the video below of, left to right, David Basoula, O’Hara, and Mason), and wrote about it in his bestselling book So You've Been Publicly Shamed.I mentioned this coincidence online and Ronson retweeted, pointing out that “fakery IS unsettling”:

Subsequently, I had what I thought was a good-faith dialogue with O’Hara about this coincidence. During this dialogue, he accused Jon Ronson of lying, confabulation, reputation management, and abusive behaviour. Then he blocked me.4

Despite dedicating years of his life to the writer, O’Hara doesn’t seem very Ballardian. O’Hara still thinks he can improve the world. He is, for instance, currently running a Covid tracking website that attempts to shake people out of their complacency about the virus. By contrast, Ballard perceives the present moment with a stark impassiveness.

In his review of Extreme Metaphors, John Gray notes this tension:

There has been much perplexity among Ballard’s critics as to his political views, with many displaying a mix of gawping incredulity and prim distaste at his departures from standard progressive positions. The editors of the current volume—an illuminating and at times revelatory collection of more than 40 interviews given over 41 years—follow this tradition, expressing bemusement at Ballard’s professed admiration for Margaret Thatcher. Why a writer presenting a view of life that subverts humanist pieties should be expected to defer to conventional political wisdom is not clear.

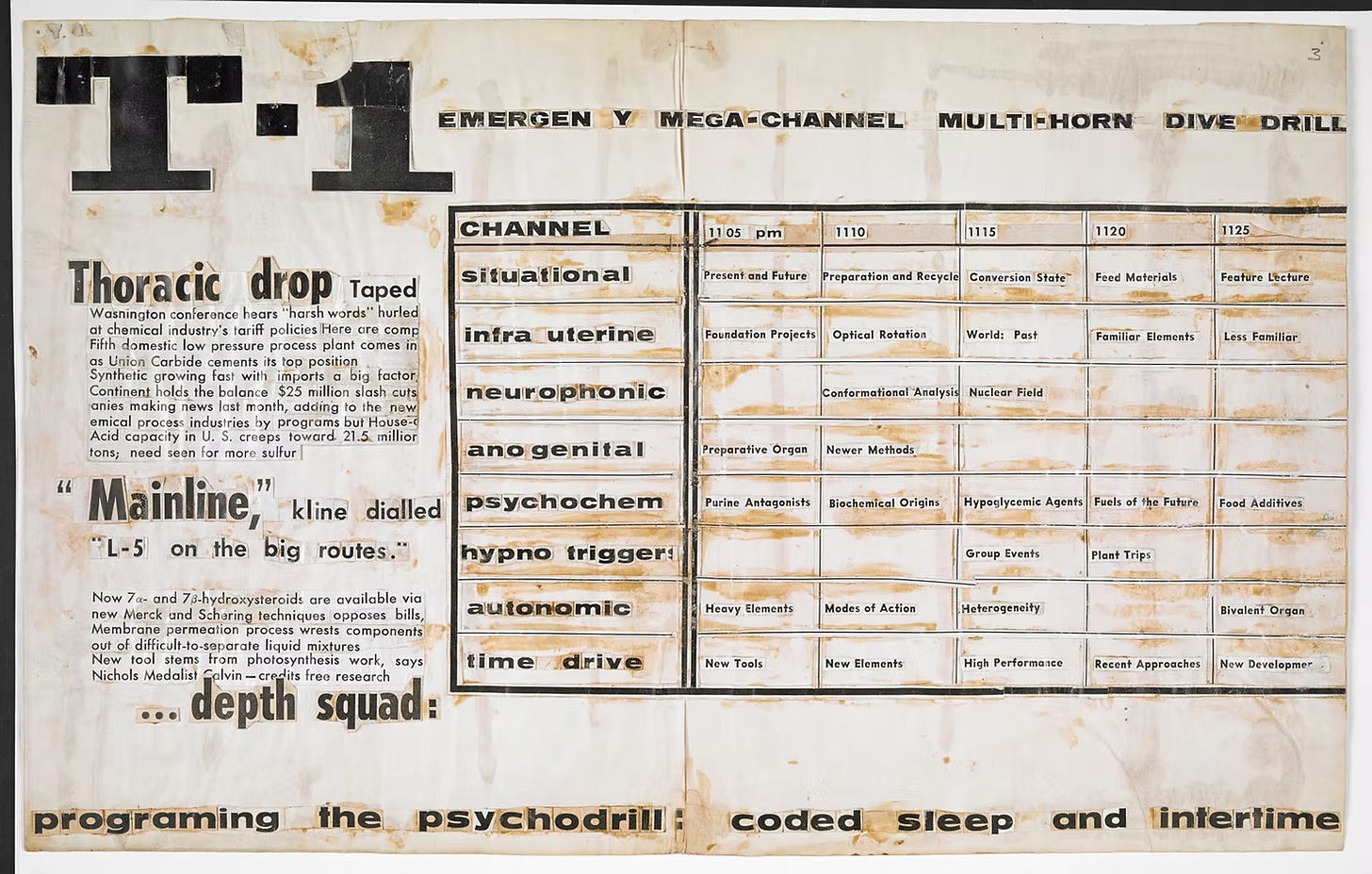

In 1984, Ballard wrote a deranged prose-poem manifesto5 which has surreal passages about his “dream of Margaret Thatcher caressed by that young Argentine soldier in a forgotten motel watched by a tubercular filling station attendant.”

Ballard rarely seems to warn us about technological or political trajectories; he is sceptical of our ability to change course. Instead, at his best, he submits to vulgar reality as it is. One of my favourite Ballard lines comes from a 1978 fanzine interview with Jon Savage:

S&D: Do you watch television?

JGB: All the time. I watch a lot of TV when my eyes are tired and weaving—also I enjoy it. I think it's terribly important to watch TV. I think there's a sort of minimum number of hours of TV you ought to watch every day, and unless you're watching 3 or 4 hours of TV a day you're just closing your eyes to some of the most—synthesis of reality, & the creation of reality that TV achieves. It's the most important sort of stream-of-consciousness that's going on! I mean, not watching TV is even worse than say, never reading a book.

JG Ballard trained as a doctor. His protagonists are often psychiatrists or architects. As a result, the non-judgmental diagnosis is at the heart of his work. For instance, Ballard saw how people cling to the intimacy of their cars and transformed it into the sexual perversity of Crash; he didn’t campaign for new seatbelt laws.6 Most artists and writers nowadays seem to believe that the world is something that must be changed, not simply observed. Morally, this is unimpeachable, but what does it do to the art …?

Myths of the New Future

When I heard that The Common Guild had a new exhibition inspired by Ballard called ‘Myths of the New Future’, I felt like I had finally been seen by an art world indifferent to my tastes.7 Although sceptical of attachment to identity labels, maybe I had just been waiting for the right one. Where do I get my Ballardian flag to wave?

Of the five artists involved—Taysir Batniji, Dora Budor, Jesse Darling, Agnieszka Kurant, P. Staff—I was only previously aware of Darling.8 However, I know Ballard pretty well and I’m fascinated by the interplay between his work and contemporary art.

For instance, did you know that Ballard created text-based collages as a way of connecting with the pop art scene of the late fifties? Or that Ballard curated an exhibition of crashed cars at London’s New Arts Lab in 1969?

When discussing this show with Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2003, he said:

I’m tempted to say that the psychological test is the only function of today’s art shows, and that the aesthetic elements have been reduced almost to zero. It no longer seems possible to shock people by aesthetic means, as did the impressionists, Picasso and Matisse, among many others. In fact, it no longer seems possible to touch people's imaginations by aesthetic means.

With all this in mind, I was enticed to The Common Guild by the promise of “hostile architectures, corporate control, maleficent technologies, civil collapse, a social body motivated by brutality and desire”. While I may not be qualified to judge these works as art, I can at least give them a Ballardian rating.

The first piece you see is a video work: Dora Budor attached a vibrator to an iPhone and filmed the world’s most expensive neighbourhood, Hudson Yards. It’s a mesmerising video, yet it never quite reaches into the strange affective world of Ballardian inner space.

Nearby, P. Staff’s spinning mechanisms convey symbols and words about alienation. It is comparable to Jenny Holzer but doesn’t feel derivative. With its arch coolness, it reminded me how close the Ballardian is to the Baudrillardian.

If my friends’ Instagrams are anything to go by, it is difficult to engage with contemporary art in 2025 without addressing the horrors of Gaza. Adorno said it was barbaric to write a poem after Auschwitz, maybe there can be no art after Gaza? Not unless you are yourself Palestinian.

Taysir Batniji collected screengrabs from interrupted WhatsApp conversations with family in Gaza. These glitchworks evoke mangled flesh and mangled lives. It doesn’t feel very Ballardian, though. Too social, too urgent, perhaps.

Agnieszka Kurant creates sculptures from the fossilized enamel paint that formed from run-off at Ford car plants. Geological time—the Anthropocene—is difficult to visualise. However, these compelling sculptures are a reminder of what future civilisations might find when our current era is over.

Likewise, Jesse Darling has picked through the detritus of our civilisation to satirise the bureaucratised present and imagine the new. Darling’s structure put concrete blocks within Lever Arch folders, erecting a new flag from the wreckage. It’s a shame they couldn't put a huge version in the central atrium of the building.

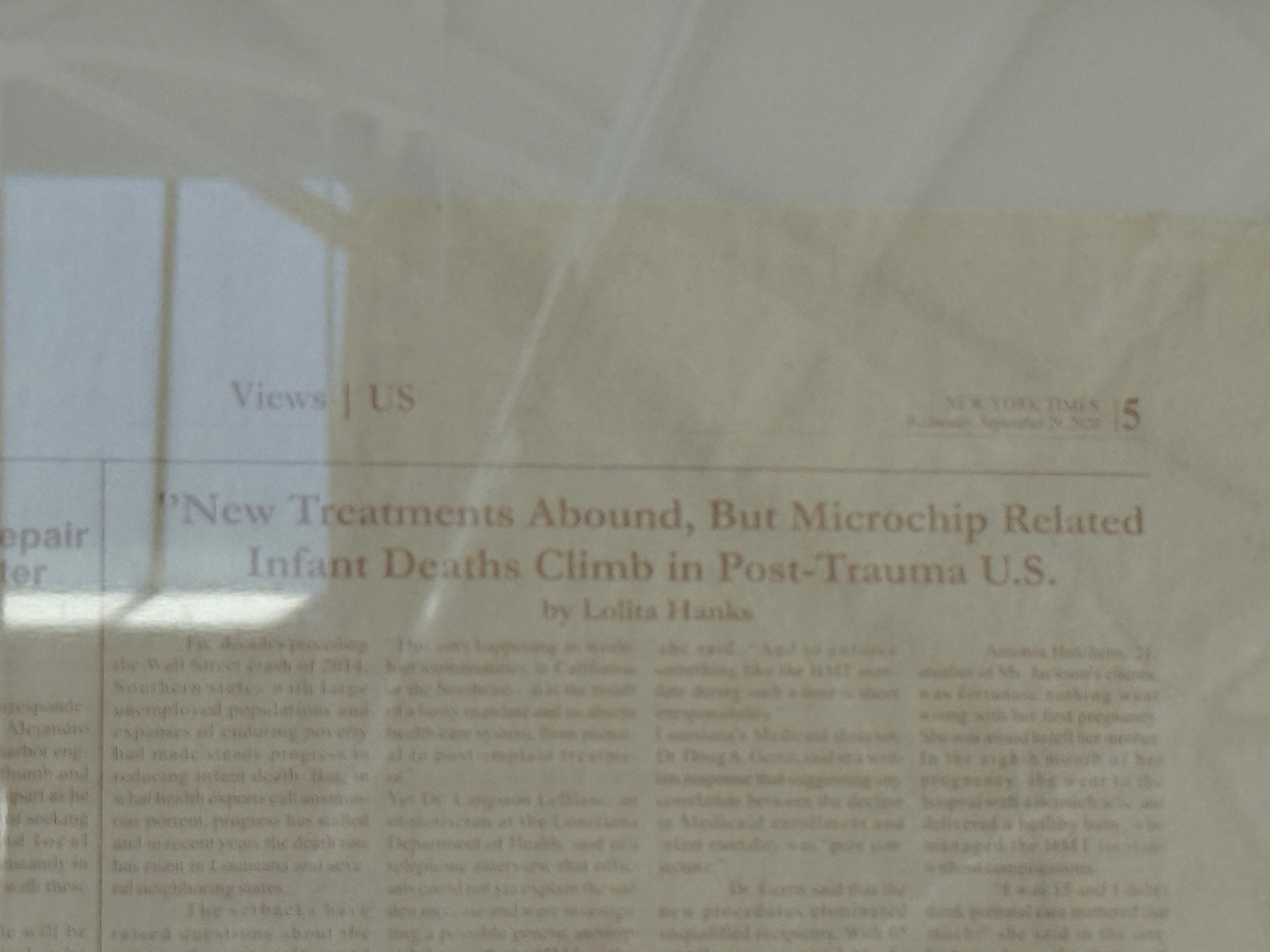

In addition to the Fordite, Kurant presents a wall of New York Times pages that appear to be from 2020 but which were actually 2007-era predictions of future news stories. Some of these are powerfully prophetic—New Treatments Abound, But Microchip Related Infant Deaths Climb in Post-Trauma U.S.—but the presentation is less interesting than Ballard’s fake scientific report Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan.

Last year, The Common Guild moved out of their previous Ballardian premises—a sterile office block in the middle of the financial district9—and into a converted Victorian school. The change in setting evoked memories of being jostled in the corridor, running late for class, the smell of PVA glue and woodshavings, and everyone’s paintings binned at the end of term. Dora Budor’s sandpaper impressions from e-bikes are more accomplished than a child’s drawings; however, the atmosphere of the school nullifies their politics.

With this enjoyable, expansive exhibition, JG Ballard is turning from a writer with a body of work into a detached adjective—Ballardian—that can be applied to the technological/social/environmental dystopia in the present day. Just as we had the Kafkaesque and the Orwellian in the twentieth century, we are now living in Ballardian times.

Yet the reason JG Ballard survives and thrives in the current year is that he observed the world without the need to propose a solution. Every artist I know is boycotting and denouncing things on platforms owned by reprehensible tech billionaires. What would it do to their art to create work that says: “This is how things are now”?

Bonus: Ballardian photography?

Walking the Golden Z the other day, I attempted to find the Ballardian in the streets. Sex, advertising, vaping, technology, apocalypse, gleaming automobiles … here are six snapshots.

Oh, and in case you’re wondering, the title is an adaptation of the line “How very Lacanian” from the underrated movie Basic Instinct 2.

“Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” was the theme of this year’s ball and produced some fun and ludicrous outfits.

Ballardian recently entered the dictionary with Collins defining it as: “resembling or suggestive of the conditions described in the works of J. G. Ballard, esp dystopian modernity, bleak artificial landscapes, and the psychological effects of technological, social, or environmental developments”

Some call it enshittification or AI slop to describe this moment of decay, but I can’t bring myself to use such ugly terms.

JG Ballard’s What I Believe published in Interzone #8, Summer 1984

I believe in the power of the imagination to remake the world, to release the truth within us, to hold back the night, to transcend death, to charm motorways, to ingratiate ourselves with birds, to enlist the confidences of madmen.

I believe in my own obsessions, in the beauty of the car crash, in the peace of the submerged forest, in the excitements of the deserted holiday beach, in the elegance of automobile graveyards, in the mystery of multi-storey car parks, in the poetry of abandoned hotels.

I believe in the forgotten runways of Wake Island, pointing towards the Pacifics of our imaginations.

I believe in the mysterious beauty of Margaret Thatcher, in the arch of her nostrils and the sheen on her lower lip; in the melancholy of wounded Argentine conscripts; in the haunted smiles of filling station personnel; in my dream of Margaret Thatcher caressed by that young Argentine soldier in a forgotten motel watched by a tubercular filling station attendant.

I believe in the beauty of all women, in the treachery of their imaginations, so close to my heart; in the junction of their disenchanted bodies with the enchanted chromium rails of supermarket counters; in their warm tolerance of my perversions.

I believe in the death of tomorrow, in the exhaustion of time, in our search for a new time within the smiles of auto-route waitresses and the tired eyes of air-traffic controllers at out-of-season airports.

I believe in the genital organs of great men and women, in the body postures of Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and Princess Di, in the sweet odours emanating from their lips as they regard the cameras of the entire world.

I believe in madness, in the truth of the inexplicable, in the common sense of stones, in the lunacy of flowers, in the disease stored up for the human race by the Apollo astronauts.

I believe in nothing.

I believe in Max Ernst, Delvaux, Dali, Titian, Goya, Leonardo, Vermeer, Chirico, Magritte, Redon, Duerer, Tanguy, the Facteur Cheval, the Watts Towers, Boecklin, Francis Bacon, and all the invisible artists within the psychiatric institutions of the planet.

I believe in the impossibility of existence, in the humour of mountains, in the absurdity of electromagnetism, in the farce of geometry, in the cruelty of arithmetic, in the murderous intent of logic.

I believe in adolescent women, in their corruption by their own leg stances, in the purity of their dishevelled bodies, in the traces of their pudenda left in the bathrooms of shabby motels.

I believe in flight, in the beauty of the wing, and in the beauty of everything that has ever flown, in the stone thrown by a small child that carries with it the wisdom of statesmen and midwives.

I believe in the gentleness of the surgeon’s knife, in the limitless geometry of the cinema screen, in the hidden universe within supermarkets, in the loneliness of the sun, in the garrulousness of planets, in the repetitiveness or ourselves, in the inexistence of the universe and the boredom of the atom.

I believe in the light cast by video-recorders in department store windows, in the messianic insights of the radiator grilles of showroom automobiles, in the elegance of the oil stains on the engine nacelles of 747s parked on airport tarmacs.

I believe in the non-existence of the past, in the death of the future, and the infinite possibilities of the present.

I believe in the derangement of the senses: in Rimbaud, William Burroughs, Huysmans, Genet, Celine, Swift, Defoe, Carroll, Coleridge, Kafka.

I believe in the designers of the Pyramids, the Empire State Building, the Berlin Fuhrerbunker, the Wake Island runways.

I believe in the body odours of Princess Di.

I believe in the next five minutes.

I believe in the history of my feet.

I believe in migraines, the boredom of afternoons, the fear of calendars, the treachery of clocks.

I believe in anxiety, psychosis and despair.

I believe in the perversions, in the infatuations with trees, princesses, prime ministers, derelict filling stations (more beautiful than the Taj Mahal), clouds and birds.

I believe in the death of the emotions and the triumph of the imagination.

I believe in Tokyo, Benidorm, La Grande Motte, Wake Island, Eniwetok, Dealey Plaza.

I believe in alcoholism, venereal disease, fever and exhaustion.

I believe in pain.

I believe in despair.

I believe in all children.

I believe in maps, diagrams, codes, chess-games, puzzles, airline timetables, airport indicator signs.

I believe all excuses.

I believe all reasons.

I believe all hallucinations.

I believe all anger.

I believe all mythologies, memories, lies, fantasies, evasions.

I believe in the mystery and melancholy of a hand, in the kindness of trees, in the wisdom of light.

One of the main reasons that Ballard has been perceived as being of the left is because transgression itself was left-coded, particularly in the 1960s. In recent years, transgression has been increasingly taking place on the right.

I asked an artist friend what they thought of JG Ballard and didn’t get much of a response. "I ... I think I saw a film about a kind of society in a tower block." "High-Rise?" "Ummm, maybe."

A few minutes later, a different artist asked me: "Why do you keep going on about JG Ballard?" He wasn't aware that the entire exhibition was a post-Ballardian exploration of the near future. Artists, in my experience, don't read; maybe words get in the way of the visual imagination. They certainly don't read Ballard. It's sad, they would learn a lot.

2023 Turner-prizewinner, Jesse Darling, whom I had seen in Glasgow International back in 2018.

I wonder if the curator Chloe Reith was working in the old premises when she dreamt up this show.

Fantastic footnotes!

Great stuff. Might go to the show. The prose-poem note 5 could do with being updated. For a start, Princess Di needs to be changed to Donald Trump. Which says a lot about how much more fucked up the world is now than it was in Ballard's time.

Can you think of a link between JG Ballard and On Kawara? Asking for a friend.