Luke Fowler

An interview with the artist whose short film Being Blue is showing at The Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow

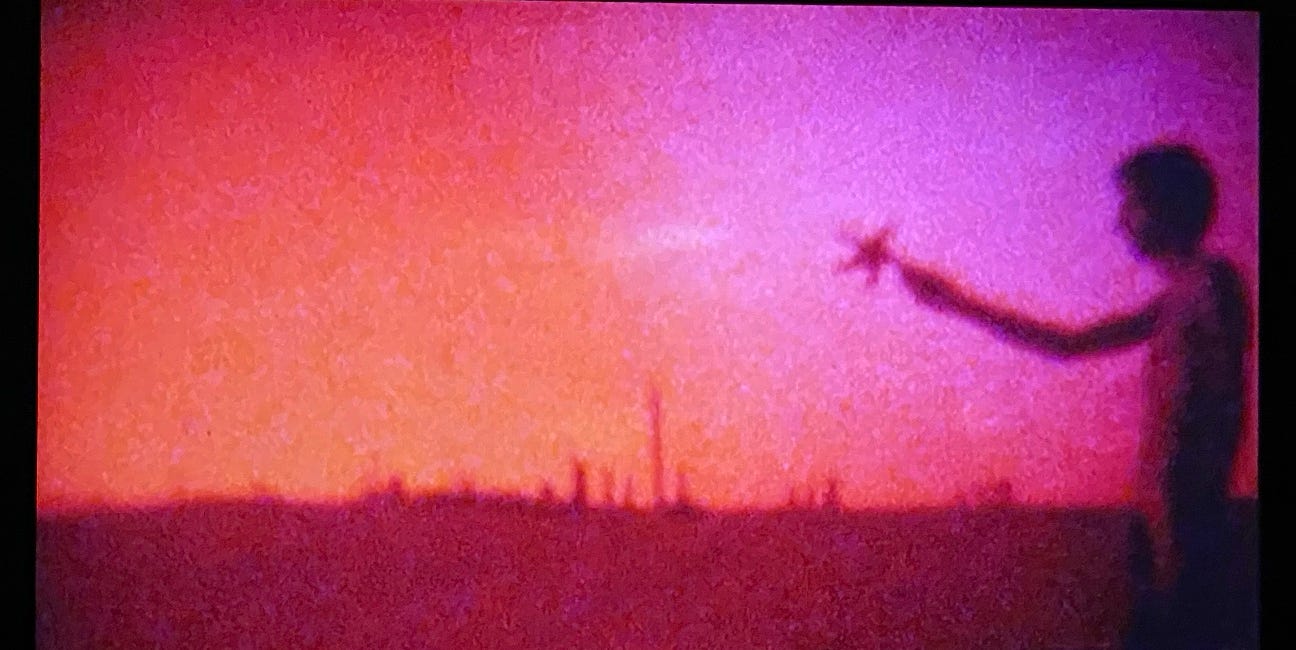

Luke Fowler is an artist, musician, and filmmaker who was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 2012. Like Derek Jarman, he often works with 16mm film and has used it to explore the lives of figures like R.D. Laing and E.P. Thompson. Fowler’s film, Being Blue, about Prospect Cottage is currently featured in Digging in Another Time: Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature exhibition at the Hunterian Art Gallery.

Neil Scott: In this new Derek Jarman show, archival materials (polaroid photos, drinking glasses, diaries) feel as important as the paintings. What do archives mean to you as an artist?

Luke Fowler: An archive is a repository of memory: the stuff of your life, the material artefacts you decide to keep. When does a collection become an archive? Is it when you're dead that it becomes an archive? Or is it when you're canonised? I'm interested in the margin between official and unofficial archives and what constitutes an archive. Does somebody who collects plastic bags have an archive? I'd argue that they do, but it's often only when it becomes enshrined in a museum that becomes “an archive.”

Did you go to the recent Duggie Fields show at The Modern Institute? Whatever you think of his paintings, his archives show that he had this total aesthetic vision of his life. Everything is part of the work. What do you think of this idea of living? Is everything art or is there a cutoff point?

The mundanity of making a living is the cutoff point. Maybe I'm romanticising it, but there was a time when it was easier to survive as an artist when you didn't have to prostitute yourself. Or maybe people like Andy Warhol were always prostituting themselves and had that Gesamtkunstwerk of The Factory. The commodification of art is obviously something that's been slowly creeping in since pop art with this model of art as an industry which so many contemporary artists have taken up.

For me, the divide between art and life is just getting the kid off to school, making his sandwiches and telling him to clean up his room. I wish I could do that in a more artistic way … When he was in the pram I would have a camera with me but it was before he had agency, before he could moan at me saying “Where are we going? What are we doing?” And me saying: “Oh, I just want to go to this derelict site on the east end of Glasgow to take a photograph of a Greek sculpture that's been left in a field.”

What draws you to Derek Jarman?

It’s his spirit of collaboration and how he brought people together. You can see his aura through the people he worked with. I’ve had the fortune of working with a close friend of mine, Cerith Wyn Evans, who also collaborated with Derek Jarman. I've also got to know James Mackay, his producer, pretty well over the years. Derek was very close to Coil, and my film includes music by Drew McDowell, who was in Coil. I also hung out with Tilda Swinton a little bit when we made this collaboration for Pringle together. So I think the legacy of Derek comes through the people that he touched.

One of the reasons the late-70s and early-80s are so potent is because there was this brief, pre-AIDS, moment of extreme freedom in terms of sexuality, combined with this strong political resistance to things like Section 28. Where is tension now? You still get the occasional reactionary headline, but their hearts are not really in it.

Yeah, you can see this when you read Modern Nature [Derek Jarman’s journals] and he's talking about people being upset by the scandal of two gay men in bed together. But there was also resistance from some of the art students. They were saying “Oh, it's very risky, but is it art?”

It was done as part of the National Review of Live Art. I always think fine art people are a bit dismissive of performance art.

Yeah, some of them are … and then obviously there are people who go to the art school and do performance art, so you can't just characterise them one way. I would go to durational performances from an early age from people who were really into Hermann Nitsch, Ron Athey and people like that. I was brought up on that stuff so I had no aversion to it. It's cool to like Cosey Fanni Tutti's work. But you wonder whether they would go to the equivalent of that now. It is fine when it's a safe black-and-white photograph of people naked, rubbing themselves in shapes and textures. But would you go to that now?

Do you have a favourite of Jarman’s Super-8 films?

I love Sloane Square, Studio Bankside, and Journey to Avebury. Those are my top three.

What do you like about these?

Just the editing. The way that he used his surroundings and the people that he had around him, which he curated into these beautiful movies. He’ll have one nice image, followed by a good image, followed by a good image, and then just cut out all the bad ones, just pile them on top of each other … and there you have your film.

Weren't you filming at Hot Mess [a queer club] recently?

Yeah, I was doing some filming for Alex Hetherington's new film, which is a portrait of Simon [Eilbeck], the deaf DJ who runs Hot Mess.

And how was that as an experience?

It was cool. Everyone was really welcoming and flattered to be photographed. They felt a bit left out if they weren't included, which is the complete opposite of the straight world where everyone’s self-conscious and a bit like "Why are you taking my photograph?"

Did it feel decadent?

I was impressed at how fabulous the outfits were, like people dressed up in costumes made from jockstraps ...

How many jockstraps did they need?

I think it was about five.

Five! Thank you, Luke.

Luke Fowler’s short film about Prospect Cottage can be seen at Digging in Another Time: Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature at Hunterian Art Gallery until 4 May 2025.

Read more about Derek Jarman:

Derek Jarman

Last week, I was delighted to be named one of Digital Camera World’s ten photographers you should follow on Substack. Thank you to all those new subscribers who took their advice.