Man Ray

Photographer of Transfixions

Until a few weeks ago, I assumed Man Ray was Eastern European. His birth name, Emmanuel Radnitzky, certainly sounded Slavic. Maybe he was like Brâncuși, who grew up in Romania and walked a thousand miles to Paris to join the Jazz Age. I only discovered my mistake after watching an interview with him from 1972 where he speaks in a broad Brooklyn accent like he’s a character from Goodfellas.

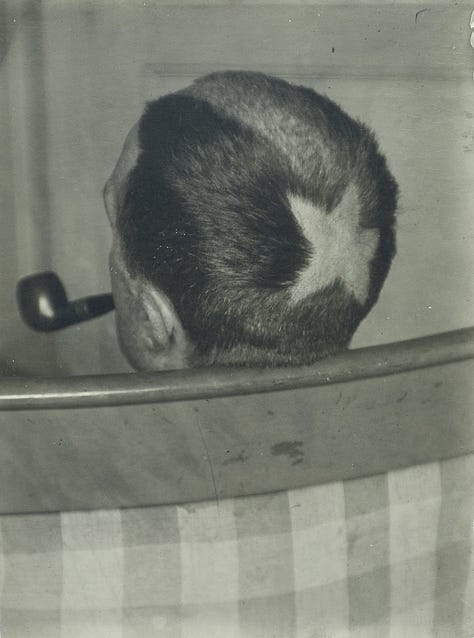

Man Ray obscured his origins throughout his life. He reinvented himself as a Dadaist and a Surrealist, becoming the great photographer of avant-garde. However, the repressed returned through his work. His famous sculptures, Enigma of Isidore Ducasse (a sewing machine wrapped in fabric) and The Gift (an iron with nails) make a lot more sense when you know that his father was a tailor who enlisted his children to help from an early age.

While Man Ray's origin story is fascinating, it is too simple to say it pre-determines his work. It just adds to the mystery of how he escaped his fate. For self-invention is a confidence trick. It requires the confidence to let go of the past, the confidence to become something new, and the confidence to convince other people to play along.

We might be interested to learn that in 1912 he studied at the Ferrer School, an anarchist colony that encouraged a radical reimagining of society. Or that, in 1915, he met Marcel Duchamp, with whom he set up New York Dada. But these details are secondary to his work. They are the preserve of the art history buff and the biographer. The real magic is in the art, particularly his extraordinary portraits.

For me, Man Ray is the photographer of Transfixion. I can't help but stare and get lost in his work. I am transported to the 1920s, like the protagonist of Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris,1 finding myself in a time when it seemed anything was possible.

I use the term Transfixion as defined in LOTE (2020), the enchanting debut novel by Shola von Reinhold. In that book, the protagonist, Mathilda, who is helping out in the archives of the National Portrait Gallery, discovers a photograph of a lost black female dandy amid the uncatalogued materials. Mathilda stashes the photo, taking it out only for Transfixion sessions. She gazes rapturously at the image, solidifying her own sense of being—“The feeling of not only recognising, but of having been recognised"—helping her to transcend the dull workaday world into a realm of aesthetic bliss. 2

Mathilda's other Transfixions include: "Jeanne Duval, Roberte Horth, Luisa Casati, Josephine Baker, Nancy Cunard, Richard Bruce Nugent, Ludwig II Bavaria and Bel-Shalti Nannar, Babylonian High Priestess of the moon god, Sin." What struck me when I saw this list is that at least three of them had been photographed by Man Ray.

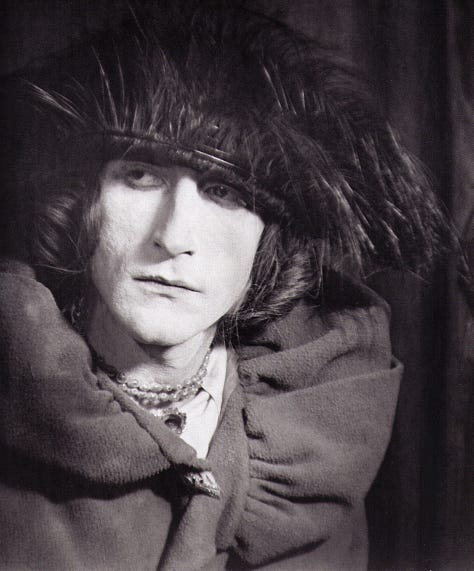

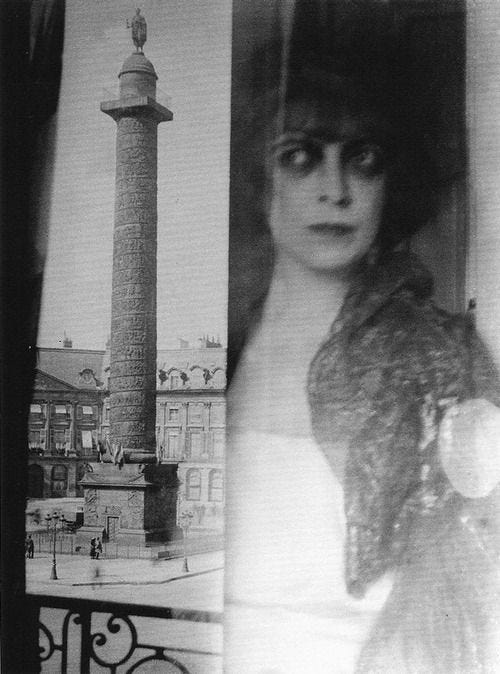

Luisa Casati, the Italian heiress who became a professional muse, is shown as a deranged blur.3 Her kinetic intensity seduces the viewer.4

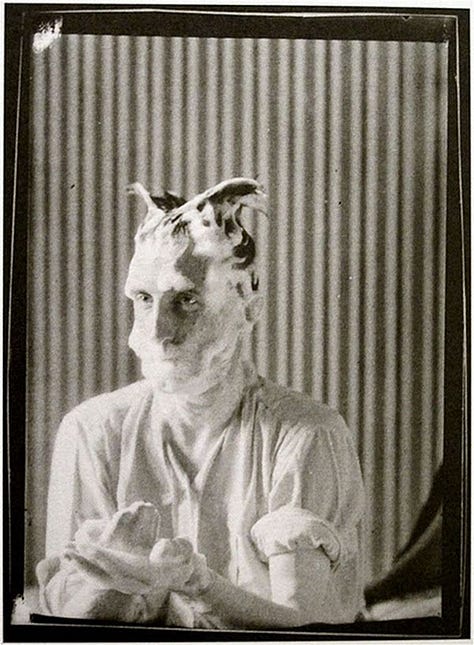

Another heiress, Nancy Cunard, wears bracelets like a living sculpture. She looks to the future with sharp definition, unencumbered by expectations.

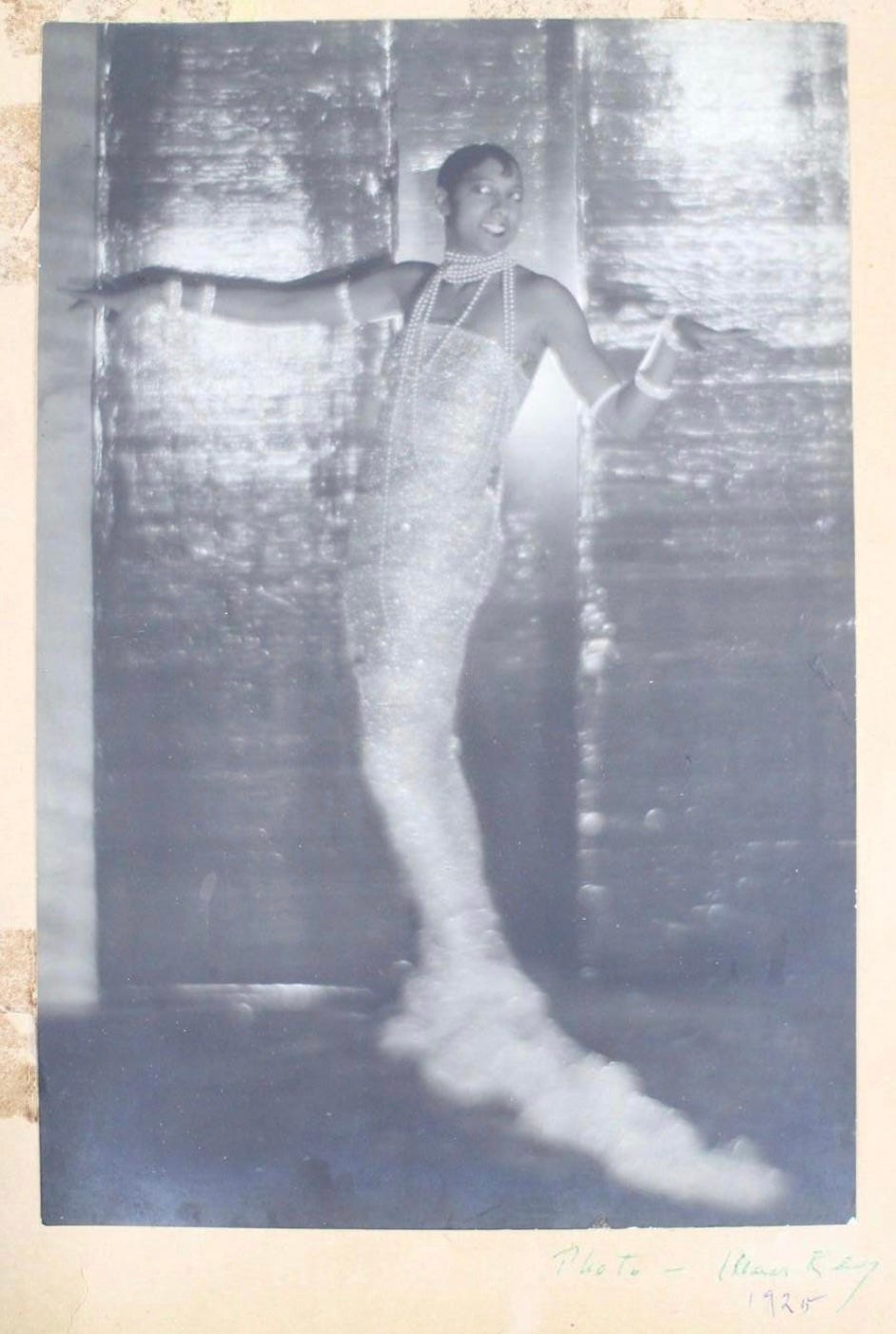

Finally, Josephine Baker, the superstar singer and dancer who posed for everyone during the 1920s but whose portrait by Man Ray I haven’t been able to find.5

After reading LOTE and viewing Man Ray’s portraits, I thought: How long can I stare at a photograph? And, what does this staring do to my sense of self? Rene Girard tells us that "all desire is a desire for being." We are mimetic creatures, but mostly this mimesis takes place unconsciously. What happens when we consciously cultivate desire?

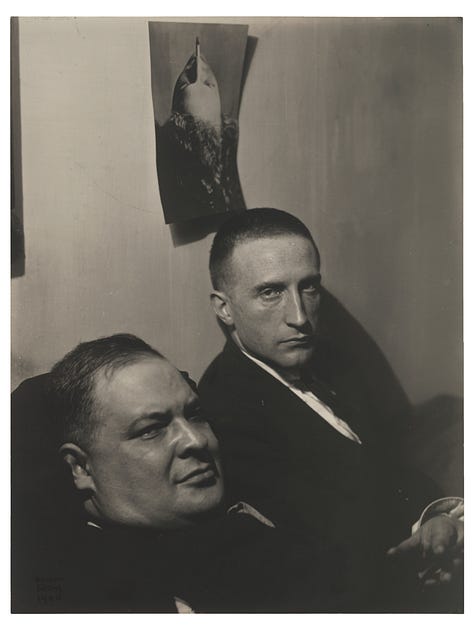

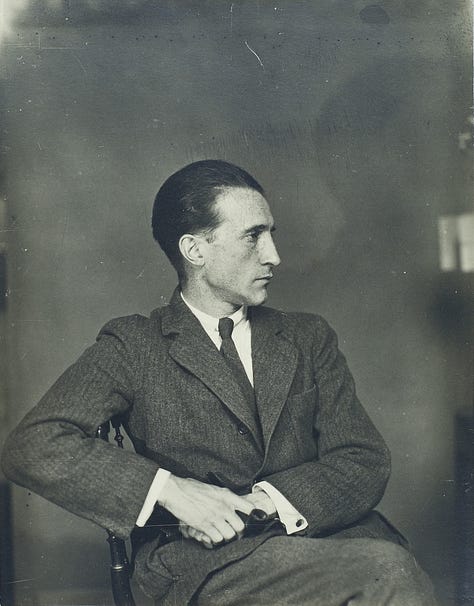

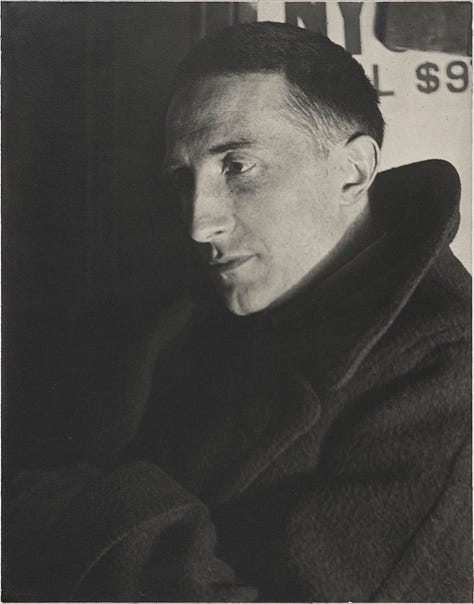

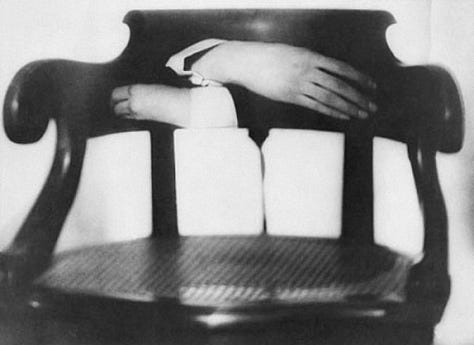

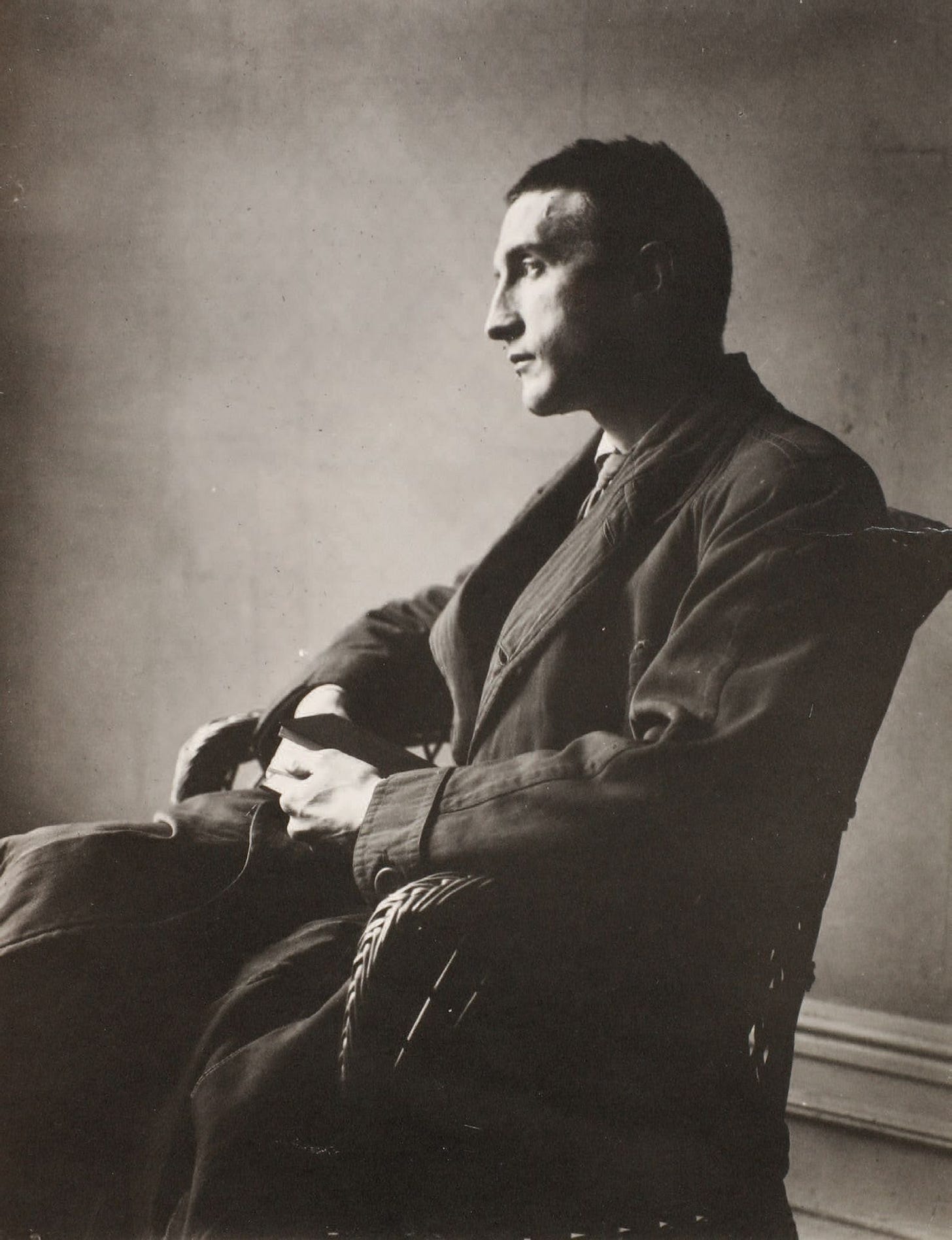

For me, the most transfixing of Man Ray's portraits are those he made with Marcel Duchamp. Sometimes these are casual snapshots, other times they are carefully conceived. In each case, the enigma of Duchamp remains. Duchamp is the twentieth century's most influential artist, foreshadowing everything that was to follow. Man Ray captures a sense of that prophetic genius.

These photographs are inspirational in the most literal, etymological sense. They are like an inhalation, making me feel large-lunged and full of oxygen. It’s a heady feeling that removes all cynicism and doubt.

In which a fictional Man Ray briefly appears.

I limited myself to a maximum of three inspections of the photograph per bus. I felt it might dissolve in my possession, outside of the archive, but instead it became more substantial, if anything materialising not dissolving—sucking in atoms, becoming more of an object, more vivid. I became fearful that commuters would notice I had stolen something almost a century old, that it was glowing with the undeniable aura of valuable old things, of masterpieces and antiquities. But, of course, no one did notice. It was not valuable.

What was beyond doubt by the time I got back was that a new Transfixion had arrived in the form of Hermia Druitt, the woman in this photograph. This was confirmed by the sensations: flashes from Arcadia. Moonlight, of a kind, sighed up and down the tube of my spine, but above all, that indescribable note which accompanied all my Transfixions was present: humming beneath the high fine rush—probably not dissimilar to holy rapture—was an almost violent familiarity. The feeling of not only recognising, but of having been recognised.

A new Transfixion.

Read more in the extract on 3am Magazine.

There are a few photographs of Josephine Baker misattributed to Man Ray, however, I’ve not yet found one that is definitely by him. This is very reminiscent of LOTE, where exploring the photographic archives can be a frustrating experience.

Interesting presentation of one of the key figures in photography, both in terms of his technical innovation, but equally for his often very intriguing darkroom decisions. For instance, the portrait of Luisa Casati - as I understand it - is simply an accident, a double exposure. The 'art' is of course that Man Ray decided to print it anyway and in time turned it into an icon of surrealism.

Now, "Duchamp is the twentieth century's most influential artist, foreshadowing everything that was to follow.", That is a HUGE statement ;0)

This reminds me of when I worked in the National galleries- at the Dean. There was an exhibition of Henri Cartier Bresson’s work and I was transfixed by his portrait of Truman capote. I would make my daily visit on my lunch break to visit him.