Notes on Class and Art

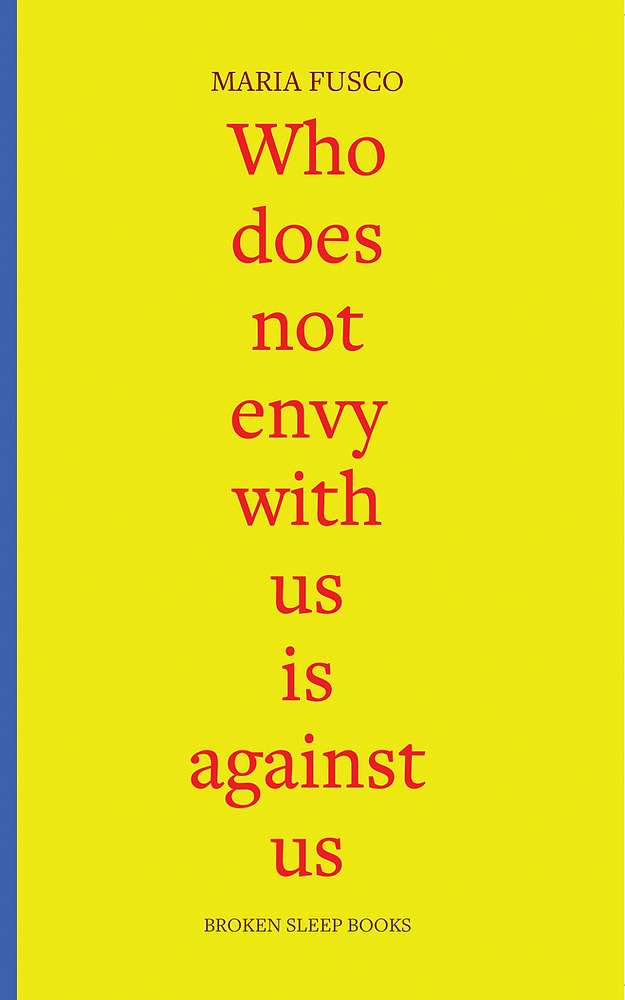

Book Review: 'Who does not envy with us is against us' by Maria Fusco

1. Life is unfair

All politics derives from one inescapable fact: life is unfair. No one gets to choose the family they are born into or the capabilities they have. If you lean right, unfairness is part of the nature of things. If you lean left, unfairness is a problem to be solved.

In a secular age, politics has replaced religion. But religion was also an elaborate system to account for suffering. For Christians, unfairness is part of a divine justice system where the rich can't pass into heaven and the poor are righteous. Likewise, Buddhists believe in karmic retribution where the sins of one life are punished in the next. In both cases, the message is to accept unfairness and do your duty.

2. Class Consciousness

For Georg Lukacs, class consciousness is an awareness of the "real motor forces of history." It is Marx showing how relationships between landowners and peasants were transformed during the Industrial Revolution, creating a working class forced to trade their labour for money.

3. "We're all middle-class now"

The line—“we’re all middle-class”—was allegedly said by John Prescott in 1996.1 He could have added: "whether you like it or not." Tony Blair's policies completed Margaret Thatcher's destruction of the industrial base and the traditional working class.

As a quote, it perfectly encapsulates the Blairite dream, a dream fuelled by SSRIs and PFIs, a dream from which we are awakening, in 2023, to the cold hard reality of freezing homes and empty fridges. Indeed, as interest rates rise and inflation destroys spending power, many people have been experiencing precarity for the first time. Class, it seems, is back.

4. Two Axes of Class

When we talk of class we tend to do so along two axes: material conditions and cultural behaviour. You can be desperately poor and still be a bohemian middle-class artist and you can be a rich yob who speaks with a broad accent, like Alan Sugar, and still be considered working class.

Grayson Perry's recent retrospective in Edinburgh has a lot to say about class but it is almost totally represented by superficial cultural signifiers. Football shirts and meat raffles equal the working class. Aga ranges and The Guardian are the middle class.

By contrast, Maria Fusco, in her new book, Who does not envy with us is against us, focuses on material deprivation. But crucially she states that, no matter how poor you are, you can never become working-class if you weren’t born working-class:2

I don't believe in social mobility: you are always the same class as the one you grew up in even if your circumstances have radically changed.

For Fusco, class is an immutable characteristic, an epigenetic phenomenon. Once you've experienced poverty as a child, it's in your bones and your blood. It doesn’t matter how much money you make as a university professor, how many operas you write, how perfect your hair or how stylish your clothes are, you will never stop being working-class. Likewise, dire poverty can never make someone with a middle-class upbringing working class. Fusco is not concerned with data. You won't find any statistics about the lifestyles of the poorest 20%. Her book is totally fused to the first-person experience of a working-class girl growing up in Northern Ireland in the seventies and eighties, a time and place where everyone knew their political enemy.

5. Consciousness of Class

Fusco's first essay, "A Belly of Irreversibles," begins in a Glasgow B&B, where Fusco hears The Sash as a ringtone playing from the kitchen at breakfast. The sectarian song takes her back to Belfast where her family lived on the bad estate. She recalls lying about where she lived to a friend and the shame of free school meal vouchers. Consciousness of class emerges from comparison.

Growing up on a fairly homogenous lower-middle-class estate outside Leicester, I was unaware of class until I was twelve and somehow got selected to play hockey for the county. Here I was surrounded by pupils from Oakham and Uppingham, posh private schools whose grounds were beautiful, palatial, full of pitches, so many pitches.3 Everyone on the team was called things like Chas, Wills, and Hector. The difference in wealth and outlook was stark.

I also recall the time my friend C. went to Cambridge University for an undergrad interview. He told me that during dinner in one of the grand halls, he asked someone: "Could you pass the salt, please?" They replied, "Oh, so you're one of those state school boys." I am never quite sure what was C.'s faux pas. I assume it was saying “please.” Maybe the upper classes don't say please?

In the second essay, "Why I write the way I write (Sally)", Fusco presents a litany of indignities suffered by her mother. Sally had a "tarnished and tiring life, a tourniquet of poverty and war" but "at least she had her words." It is a tender, troubling essay about the shape language takes under pressure. Life can oppress you with neglect, conflict, and poverty but you always have the satisfaction of telling someone to "stick yer nose up my hole." If only my friend C. had such words available to him.

6. After Identity

One of the last pieces of legislation from the Blair/Brown Labour government was the Equality Act 2010, which established 9 protected identity characteristics — age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation. Class is not a protected characteristic, but some argue it should trump the others. For instance, Walter Benn Michaels wrote, also in 2010, "identity politics [...] does more to legitimate that inequality than to oppose it."4

In the art world, preferment often comes from a person’s marginal identity status, even if they went to a private school.5 They are the ones able to navigate the arcane bureaucracy set up by the professional-managerial class. The overall effect is that diversity of identity can serve to obscure uniformity of background.

7. Class and Attachment

What do you get for the person who has everything? Nothing. By nothing, I mean non-attachment or liberation from material concerns. Western Buddhism is designed for the person who has everything. For the person who has nothing, however, non-attachment is not a serious proposition.

In Fusco's final essay, which gives the book its title, she uses envy as fuel to take a series of hatchet swipes against the middle class. This class used to be known in the 18th century as the middling class: "A class that is trying." Fusco channels this resentment against those who have slighted her. There is the colleague who trampled over her coat on the way to the toilet. The passengers who barge past her on the underground. The philosopher who eats Upper Crust baguettes and then occupies the toilet for hours. In each case, the idea that they are insults is largely generated in her mind. The envy mood, she tells us, "requires imagination."

As a (lapsed) meditator, I can't help but empathise with people’s suffering. It's not difficult for me to imagine that the colleague was caught short, desperate to pee, and preferred to climb over her coat rather than wet himself. Or that travellers are oblivious to Fusco due to a sense of economic urgency. Or that the philosopher hates himself and eats to fill a void. Envy here precludes empathy.

Individual examples are subjective and open to interpretation. It is the accumulation of slights that creates the class experience. However, the coping mechanisms Fusco claims are a direct result of the oppression she experiences from the middle classes, sound like social anxiety that could be experienced by anyone:

dissociation; excessive alcohol consumption; hiding in a locked toilet cubicle; hiding in a kitchen; hypochondria; laughing extremely loudly when you don't find what you are laughing at funny; making yourself useful to others like, for example, taking it upon yourself, without being explicitly asked, to offer a bowl of crisps around the whole group; self-depreciation; resignation.

Middle-class people do these things all the time. At least, the ones I know. Perhaps they are not posh enough.

Despite these qualms, I do recommend Fusco’s book as an account of the traumatic effects of class. It is a poetic provocation and a thorn in the side of the complacent. Class is here and must be discussed.

However, he disputes saying it:

Lord Prescott has asked us to point out that a leader article wrongly attributed to him the phrase "we're all middle-class now". The widely misquoted line derives from an interview with BBC Radio 4's Today programme in 1996, when the then Labour MP in fact said, "I'm middle-class", and later clarified that he was "a working-class man with working-class values" living a middle-class "style of life".

Corrections and clarifications, The Observer, 5 August 2012

It is notable that the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, which is specifically focused on alleviating poverty, barely ever mentions class. It is no longer a helpful term. What they do talk about is poverty. Poverty is measurable. Poverty has material consequences. It doesn’t only exist in your head.

Oakham is £43,905 per year for boarders. It is also now located back in Rutland rather than Leicestershire.

Full Walter Benn Michaels quote: "Racism is wrong, sexism and heterosexism are wrong; discrimination of any kind is wrong, and it's a good thing to oppose it. But it isn't discrimination that has produced the growing economic inequality in the U.S., and identity politics today—with its irreducibly proportional vision of social justice, its defining goal of equality between identities-does more to legitimate that inequality than to oppose it."

I look forward to seeing an equivalent Twitter account to JournoSchool, which presents headlines accompanied by the educational background of the journalist.

I’ve always remembered the shock of seeing Oakham School sports facilities….. if only 🥹