Photography as Conceptual Art

A conversation with Roger Palmer on the publication of BLOODSTREAM/LAZARETTO

At the beginning of this year, I resolved to boycott art. I couldn't endure another inept papier mâché sculpture about the Anthropocene. Instead, I was going to focus exclusively on photography.

In my mind, this was a sharp division. Art, with all its pretension and folly, was on one side and photography—engaging and direct photography—was on the other. As the saying goes, "The man who chases two rabbits catches neither." Photography was my rabbit.

Unfortunately, I’ve discovered photography can be art too: fine art, conceptual art, and even land art. Photography is not just a noun but a verb.

Roger Palmer (b. 1946) is not well-known as a photographer yet he is hugely accomplished as an artist. He has had over a dozen photobooks published. His photographs have been acquired by the Tate, the V&A, and the South African National Gallery. He is an Emeritus Professor at Leeds University and was one of the three founders of Glasgow School of Art's garlanded MFA programme.

Palmer was also the first photographer I ever saw who had an exhibition at Glasgow’s Centre for Contemporary Art—a venue at the vanguard of blobby ceramics. A couple of days before the show opened, I remember seeing this dapper man with a pork pie hat inspecting the hang. That must be the artist, I thought. It's rare to see a dandy in Glasgow—the people are good at cutting tall poppies—so I was excited to see the work.

However, the exhibition left me, if not cold, then certainly nonplussed. Most people, when they don't like something, will ignore it and move on. However, my instinct is to assume that I lack the aesthetic sensitivity to decode the work. Art history is a conversation across time: one can't just barge in and infer the context.

Palmer’s photography involves linguistic ambiguities, historical traces, conceptual art practices, and land art-style journeys. It's not enough to look; by taking the time to engage with the intellectual background the viewer gets a far richer experience than can be had with a mere image. That's the theory, anyway.

When David Bellingham's Wax366 imprint announced the publication of a new Roger Palmer photobook, BLOODSTREAM/LAZARETTO, I saw an opportunity to try to find out what I was missing, and maybe even learn something. We met on a rooftop bar overlooking the river Clyde, the setting of the new books ...

Neil Scott: When I first saw the BLOODSTREAM pictures, I assumed it was a lockdown project, a way to get out of the house. But you started it before lockdown, in January 2020. What initially drew you to make a project about the Clyde?

Roger Palmer: Having worked in faraway places for several years, I wanted to do something local. I often ride my bike along the Clyde and on several occasions have noted the remains of a series of angled slipways a short distance downstream from the Riverside Museum. Early in January 2020, I managed to reach a wall next to these and made several photographs. On subsequent rides to different sections of riverbank leading to a preliminary idea for a black and white photographic project focusing on the river. But it was much later that BLOODSTREAM began to take shape.

I read about shipyard workers and others, including employees at the Singer sewing machine factory. Immediately after the First World War and at the time of the Spanish flu epidemic, a growing dissatisfaction with working conditions led to industrial unrest on Clydeside. In 1919, when demonstrations took place in George Square, scuffles occurred between striking workers and over aggressive police. The Home Secretary decided to place the army on standby and with the leading union shop steward thought to be in contact with Lenin, the industrial heartland of greater Glasgow acquired the sobriquet, ‘Red Clydeside’.

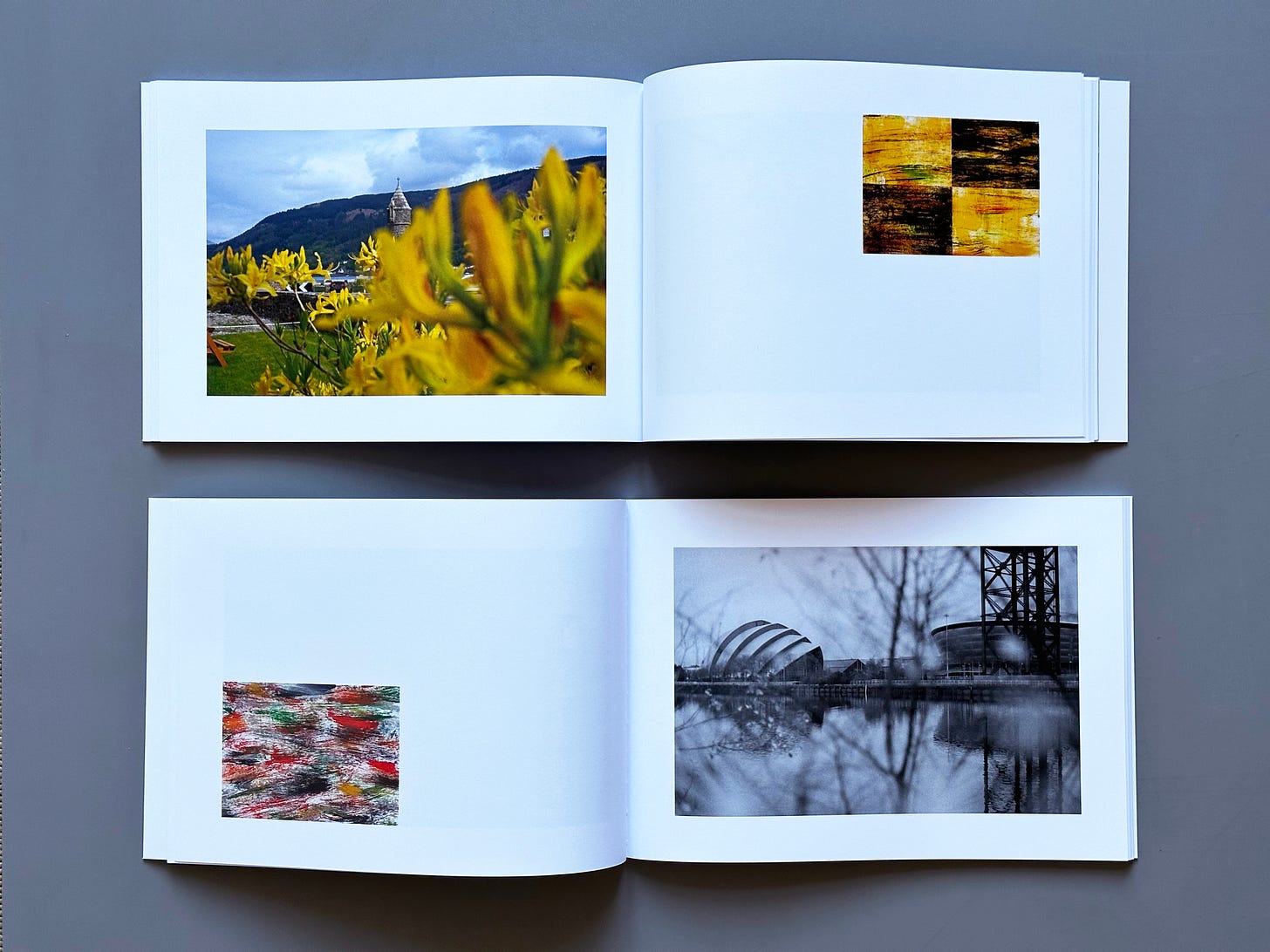

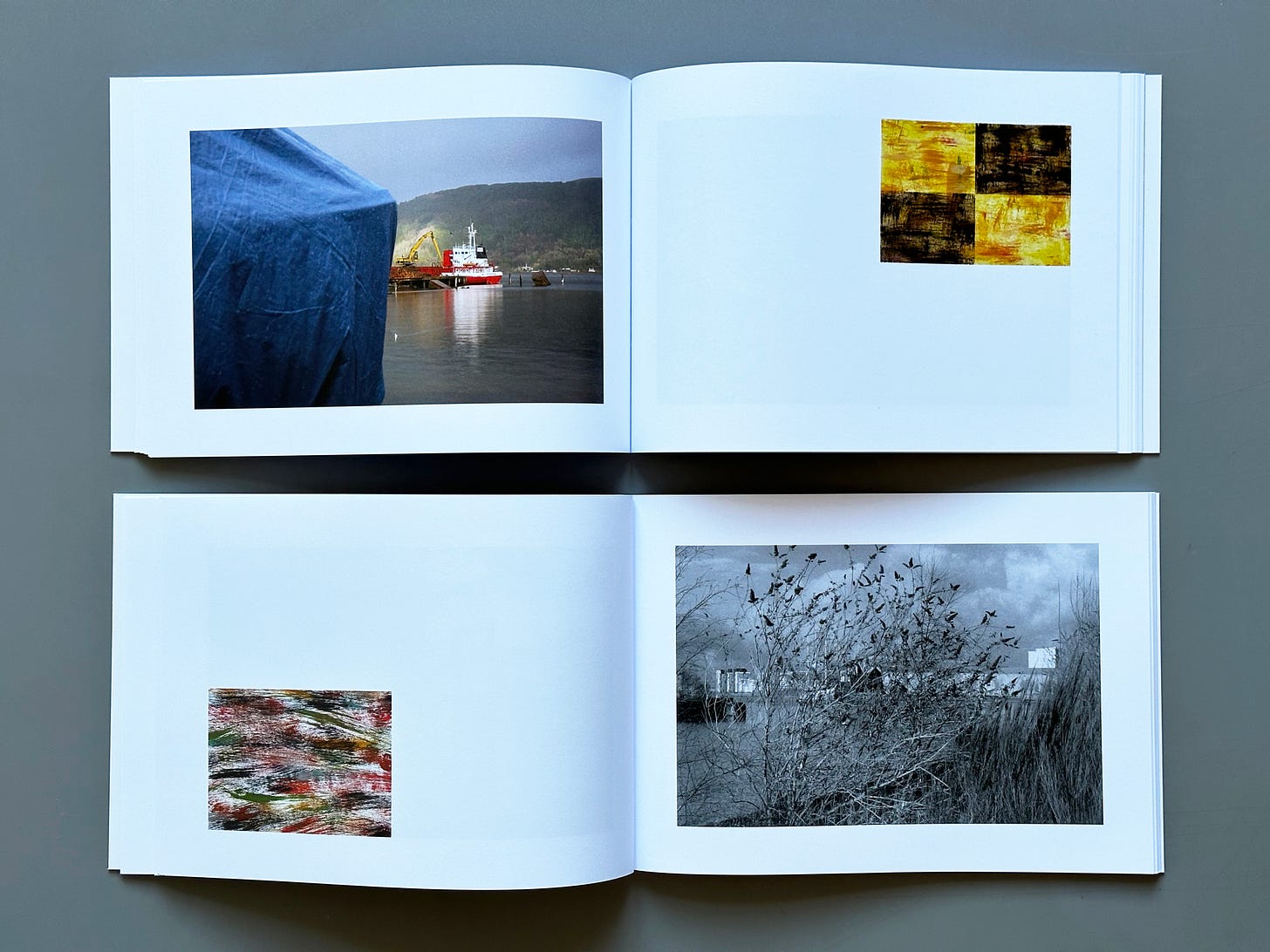

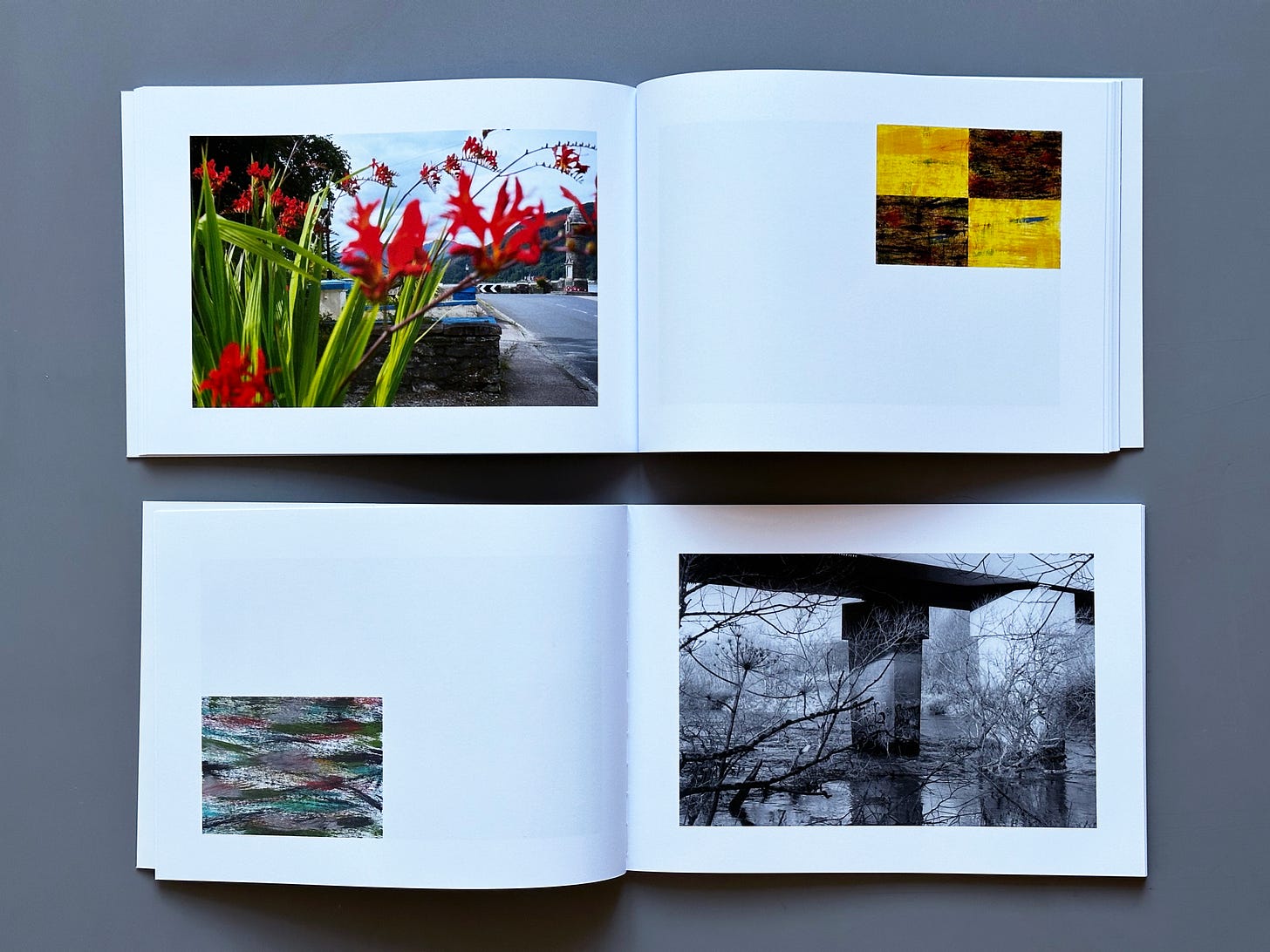

In March of 2020, returning from a visit to South Africa a few days prior to lockdown, I bought a hardback sketchbook with a view to sequencing photographs for a future book project.1 It didn’t take long for me to realise that the sketchbook was inappropriate for this task and that was when I noted the paints in my home studio that my grandkids use. During the first period of lockdown, I began messing about with acrylic paint and watercolours in the sketchbook, safe in the knowledge that nobody would see my secret work. It was towards the end of 2020 that I first began to place on my studio wall tiny red paintings amongst River Clyde work prints.

There seems to be a kind of urgency to those paintings, whereas the photographs are more contemplative. How do these two speak to each other?

There's a sense of urgency in making photographs at the time of exposure. I don’t use a tripod; all pictures are made with a hand-held 35 mm camera using a standard lens and one type of film. I print my b/w photographs, first as a selection of work prints, before identifying a group of key images for making exhibition quality prints. I’m always surprised at how long the process of editing from a stock of initial images takes.

Although the paintings display a certain urgency as layers of quick, relatively dry brushstrokes, they are also the product of lengthy consideration and editing. Just as the final group of 32 photographs follows the flow of the Clyde through Glasgow and beyond, so the accompanying 32 paintings reveal gradual, perhaps subtle changes of colour that might encourage consideration of the river and its history.

When my friend Pablo saw your work, he teased you that you were hiding behind bushes. But it seems to me to be about avoiding cliches. We've seen these buildings a million times before. They're in postcards.

I'm not hiding but simply trying to generate pictures that problematise photography. I'm interested in what happens between the moments when I make a series of exposures and the subsequent activities of printing, looking and editing. My hope is that I’ll arrive at something new, a picture that has a certain kind of ‘stop and think’ quality. In BLOODSTREAM as in other projects, the decision to ‘interrupt’ familiar views with out of focus, organic material that resists identification acts as an assertion of the two-dimensional photographic surface. And these abstract areas of the photographs can also make connections with the accompanying paintings.

The way you describe the project doesn't sound like it's an intentional conceptual practice.

The intentionality or understanding comes through a slow and laborious process of working. Initial, often vague ideas are tested and either discarded or modified through continuous engagement with my material. I don’t believe that anything of interest will emerge if one simply remains faithful to an initial idea. It’s how an idea can develop into something unpredictable that is of interest.

The second project in this slipcase, LAZARETTO, is directly a lockdown project in which you visited a former quarantine station every 40 days.

With lockdown loosening, we were able to travel further afield, and the last two pictures of the BLOODSTREAM series were made in the Firth of Clyde at Cardross on the northern shore and Port Glasgow to the south. I decided to go further downstream to Holy Loch, the site of a former US submarine base. But I quickly realised there was little chance of developing a project on this theme.

Cycling back past the war memorial at Lazaretto Point, I made a few pictures of graffiti on a nearby bus shelter window. It was through reading about Lazarettos as places of quarantine, that I then decided to return to the same site 40 days later, hoping to find something different. The word, quarantine comes from the Italian, quarantina, meaning forty. As a quarantine station had existed at Lazaretto Point in the early C19th, it seemed appropriate to return every 40 days. By January 2023 I had made sixteen visits at which time I thought that I had made enough pictures to decide on a set of 40 that eventually became a parallel to BLOODSTREAM. In both projects, photographs are paired with paintings. For LAZARETTO, I developed a series of 40 acrylic paintings loosely based on the ‘L’ or LIMA maritime flag.

With the covered boat and the picket fence, it feels like there are references to Robert Frank and Paul Strand. I don't know if this is self-conscious quoting from photographic history or if that doesn't even register.

Well, if I was younger and eager to stroke your ego, I’d say “Yes, that's right.” But it's not true. Not consciously anyway.

I am curious about your relationship to the landscape tradition in photography. It seems to me that the Glasgow School of Art photography department still bears traces of Thomas Joshua Cooper who was mentored by Ansel Adams.

I first met Thomas at Trent Polytechnic in Nottingham. In 1976, I was appointed artist/ photographer in residence at Trent at about the same time that Tom was leaving. Working in Photography at Trent was my first contact with ‘photographers’ as opposed to artists working with photography and I became friends with Raymond Moore whose work I greatly admired.

I had a rather haphazard approach to photography that included, drawing and printmaking - the antithesis of the Ansel Adams tradition. I had studied painting and printmaking and started working with found photographs in the late 1960s before buying my first 35mm camera in 1971 when I was teaching at Newcastle University. At that time, I was aware of the work of artists such as Richard Hamilton, Jan Dibbets, Ed Ruscha, Victor Burgin, Martha Rosler and Richard Long, whose photo-based work addressed conceptual and minimalist thinking.

And how did you end up in Glasgow?

Thomas invited me to teach in the newly accredited Fine Art Photography Department; an invitation I accepted on certain conditions. First, I proposed that the department could act as an ‘umbrella’ for all areas of fine art practice. If students were able to discuss their work in the context of photography, they would be free to work in any medium. Secondly, I didn’t want to be responsible for darkroom instruction as my knowledge of photographic techniques was very limited and I preferred to contribute through critical discussions with students. Thirdly, I proposed that Photography students should have individual studio spaces and that we would critique their work in these studios. For two years I taught at GSA on a 50% contract before accepting a full-time post in 1987. At that time, I was also asked to develop a new GSA MFA course alongside Sam Ainsley and Sandy Moffat.

You’ve spoken in the past about visiting the influential conceptual art show When Attitudes Become Form, When I see such things, I ask myself what questions it was trying to ask at the time and how do we relate to that now? It is part of the canon; do we just leave it in the archives or does this still resonate?

At that time in 1969 I was studying printmaking at Chelsea School of Art, but I don’t remember precisely why I visited the ICA exhibition. I do recall that seeing the show was a difficult experience although there were some pieces I instantly liked, such as a work by Barry Flanagan of projected light on burlap sacks. There were a lot of words everywhere, a lot of straight lines, and little or no colour.

I wandered around the show more than once, struggling to come to terms with work that was largely unfamiliar. But I do remember a moment of clarity that occurred several weeks later while I was washing dishes. If I refer to the English idiom ‘the penny drops’ as a moment of sudden understanding, my experience was that my When Attitudes Become Form ‘penny’ shifted a little, which served as an indication that I was still processing the exhibition at a moment when my hands were busy in a kitchen sink. If that ‘penny’ had moved once, I thought it might well move again as further indication that the experience of seeing an exhibition doesn't end as you leave the gallery. And so it proved, as the ICA exhibition and many that followed have stayed with me as formative experiences.

In 1968, Richard Hamilton designed the Beatles LP cover for The White album. There was this moment of conceptual art going into the mainstream with the biggest band in the world. Was London Swinging when you went there in 1968?

Yeah, I guess so. The nearby Kings Road was lively, but I didn't have such a nice time at Chelsea School of Art in 1968/69. I was a bit lonely and unhappy at living in what seemed like the far suburbs of London, in south Clapham. Perhaps Clapham might be considered as part of inner London now, but it felt like it was far from where I wanted to be at the time.

You’ve previously talked about not wanting to take a strong political viewpoint and giving people the comfort of being able to easily identify where you stand on issues. But we're now living in an era where politics are central to a lot of artists' work. What do you think about the current situation with politicised artmaking?

There's always a danger that if one attaches one’s work to a specific cause, it reduces the possibility of speculation on the part of the viewer. I've never been very excited by work that has a clear message or agenda. There must be some sense of the equivocal, which reflects how an artist considers uncertainty as an important aspect of making work.

In 1985, shortly before my first visit to South Africa where I made photographs for what became the project, Precious Metals, there was a particularly terrifying event in the Eastern Cape where a group of unarmed demonstrators were shot in the back by police. At this time, British newspapers and television were often publishing images of armoured SA police vehicles attacking township residents who could be seen running for their lives through smoke and dust. With plenty of this journalistic imagery available, I didn’t want to make work in South Africa that did something similar. Instead, I eventually made Precious Metals in which monochrome images of seemingly uneventful spaces are combined with texts that alluded to historical and political responsibilities, but in open-ended ways that might encourage a multiplicity of readings.

When I spoke recently to Ewan Morrison (who studied on the Fine Art Photography course), he was delighted to hear that I had been in contact with you. He told me: “Roger will get his camera out. He'll find a view he likes and then just before he takes a photo, he’ll turn the camera around at what was behind him as a way of denying the kind of colonial gaze of the taking.” I don't know if that's a literal work that you've done?

No, it’s not (well perhaps once!). But it does remind me of a newspaper review of a show I made in Dublin in the mid 1970s. On my way back from Connemara I bought a newspaper which carried a somewhat bemused review of my exhibition by posing the question - what kind of photographer is Roger Palmer? The reviewer’s answer was that Mr Palmer is like an unfortunate and useless uncle whose family photos invariably fail to include any of his supposed subjects! It was frustrating, if faintly amusing at the time, a cheap way of criticising minimalist pictures of expansive areas of grey rock under misty skies

How do you relate to the human? There are some human beings in your photos, some from the back in SPOOR. So there's not a total absence of humanity. What do you think adding a human being does to a photograph?

I don't add them. On occasion, such as in the book SPOOR, it seems pertinent to include people in some of my pictures. But they are not identifiable as individuals, only as figures in landscapes. I have only a passing relationship with people I encounter when working in rural South Africa; people who, for the umteenth time in their life, are walking the track between town and township; a track which follows a disused railway.

My first work that includes human figures is an artist’s book titled PHOSPHORESCENCE. It was the hasty product of a commission for the 2014 Commonwealth Games. I had made a successful proposal to Creative Scotland to spend the period of the Glasgow Games in the smallest Commonwealth country - the Republic of Nauru in the Pacific Ocean. Each morning, as I went for breakfast at my hotel, I'd see on TV a journalist from Fiji or New Zealand reporting on events in the Games earlier that day. So, I invariably began each day with a live view of early evening on the Pacific Quay in Glasgow.

I spent three weeks on Nauru and made a series of digital pictures to be able to complete my project by the end of 2014 and fulfil the terms of my commission. But it wasn’t easy to work in a tiny country whose economy was so depressed and dysfunctional. More than once, I was accused of being a journalist spying on conditions for detention centre inmates. On other occasions I was attacked by packs of feral dogs.

In 2014, a big problem for Nauru was its 90% rate of unemployment. Those who were employed were primarily working for migrant detention camps that Australia had located on Nauru in return for offering economic aid. Nauru was a very different place in the early 20th Century; it was one of the wealthiest nations in the world through its rich phosphate deposits. But by the 1970s phosphate mining was largely exhausted and Nauru rapidly became one of the world’s poorest countries.

During my visit I found it difficult to find fresh fruit and vegetables. I think I paid 25 Australian dollars for three bananas and a couple of apples soon after a rare delivery arrived from Australia. While at the shop I met the manager of my hotel and asked her to buy broccoli. Later that day, I went to the hotel restaurant and ordered dinner which to my surprise, was served with an extra plate overflowing with broccoli!

That does sound fun, but when I hear this I think: why would that never be in a Roger Palmer photograph? Not that particular mound of broccoli, but these people, these things happening ... where is the exclusion zone?

That's a good question... I think this is where the nature of my exploration of photography comes into focus. I'm primarily interested in making things that ask questions about the medium. For me, viewing artworks, including photography, is primarily one of engaging with conditions of encounter, whether they be in a gallery, a book or in the public domain. I'm much less interested in making visual statements that relate to my own experiences or to fleeting contact with people in a random place. I'm therefore not interested in contributing to documentary or issue-based photography.

You have a circle of concern. The worst thing one can do is say yes to everything. One has to say no to a lot of things to say anything at all. For me, engaging with your work has been a discovery process, the gradual enlightenment of trying to understand the references as someone who doesn't come from a fine art background …

I was at a dinner party a while back where I briefly spoke about structural film. When another guest asked me to explain the term, I did my best to describe how artists’ filmmaking tends towards reflexivity through acknowledgement of its own physicality, duration and projection conditions. Later I suggested a few examples he might want to watch on YouTube. When we met again, he said: "The thing is, Roger, I just don't get it." I sympathised completely because there's no such thing as getting it, as for me, ‘getting it’ suggests closure.

With Trump in the White House and nationalism and populism on the rise, it feels as if the space for post-modern reflexivity is ending.

I wonder what the world will be like in 20 years? I won't be here you’ve got more time ahead of you than I have.

You might be! Photographers often live a long time … Imogen Cunningham and Elliot Erwhitt lived well into their 90s.

Maybe artists who work with photography don’t.

You still get to go outside every day …

It looks unlikely that I’ll stop working, at least not in the foreseeable future. Most artists, writers, musicians do their best work in early or middle age but then their moment passes. As I am well into old age, I might jokingly describe myself a submerging artist while the world of art moves on. I'm just going to keep doing what I'm capable of, physically, intellectually, economically. Whatever time is left, whether it's a day, 10 years or more, I’ll just keep working, but ever more slowly.

Thank you, Roger!

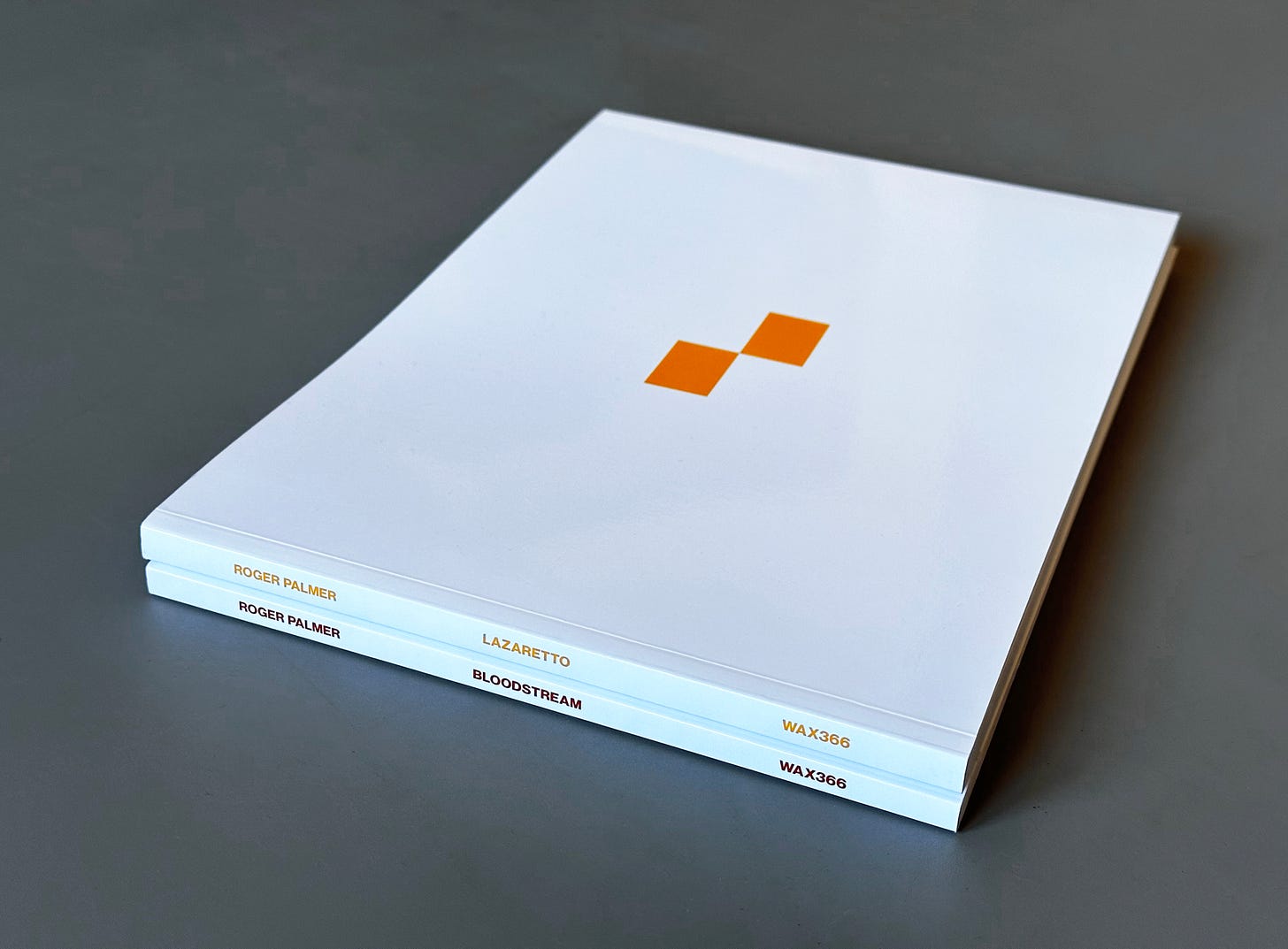

BLOODSTREAM/LAZARETTO, two artist’s books contained in a single slipcase are available at WAX366 priced £40.

A STONE’S THROW, Fotohof edition, Salzburg, 2021