Richard Prince

Inappropriation artist

Richard Prince is to photography what Marcel Duchamp is to sculpture. Just as Duchamp appropriated readymade, mass-produced objects and turned them into art, Prince re-photographed the photos of others and sold them as his own work.

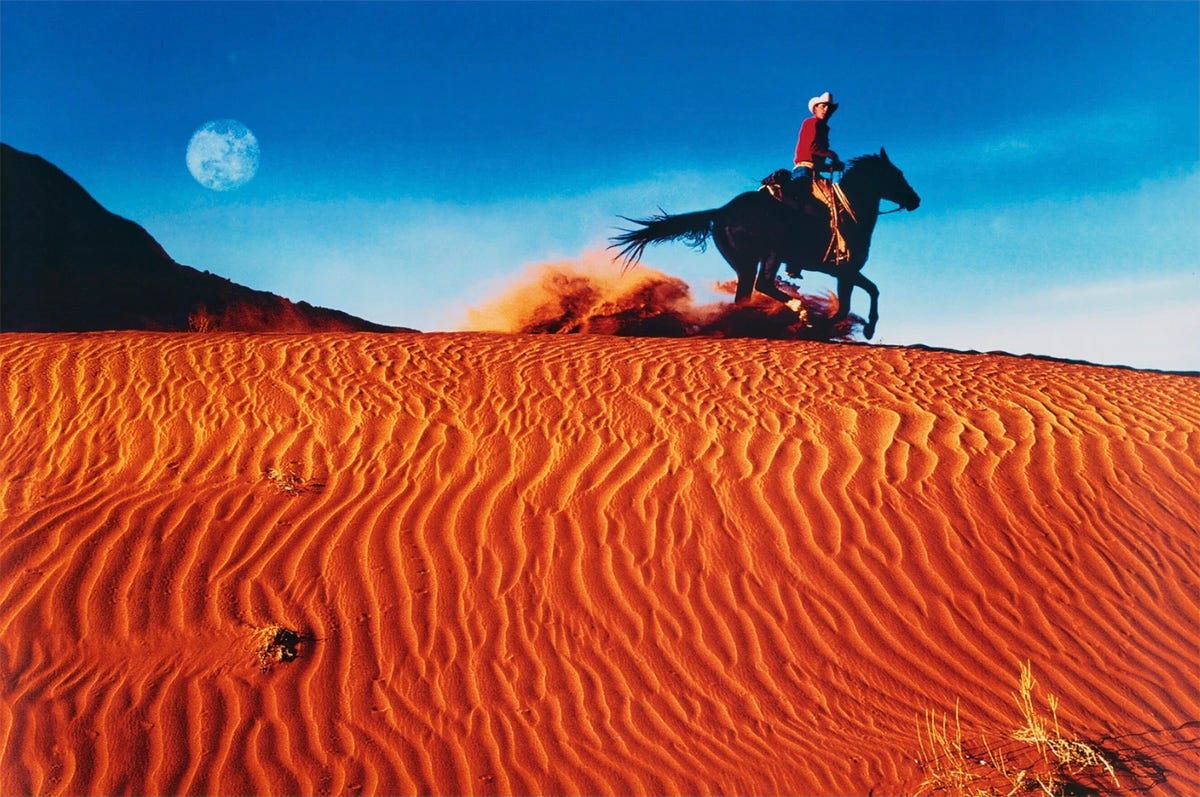

And boy, do they sell. In 2024, the three most expensive photographs sold at auction were by Richard Prince. His Untitled (Cowboy), 1997 went for an eye-watering $2.6m. Unlike most photographers, Prince only makes two copies of each artwork; his prices are high because they have genuine scarcity.

Nevertheless, Prince is widely despised in the photography community. Check out

’s recent post.1 The reason for this hatred is that Prince never acknowledges the original photographers. He ignores men like Sam Abell, Jim Krantz, and Norm Clasen who went into the Wild West to shoot these iconic images. Prince has faced countless legal challenges for copyright infringement. Yet, the market appears indifferent.To those in the art world, bourgeois concerns about authorship are secondary to the concept — the concept! — of "Spiritual America". Prince is a post-Warholian visionary who takes Cowboys and nude pics of girlfriends out of the confines of magazines and places them in a gallery for us to appreciate their mythic quality.

It’s rare for Prince to talk about his work. However, a recent appearance on Rick Rubin's Tetragrammaton podcast helped to clarify his motivation. Prince rejects the idea that such photographs have authorship because they were produced by art directors for commercial purposes. As far as Prince is concerned, he is like a musician using samples. He takes things in the culture and turns them into ambivalent celebrations.

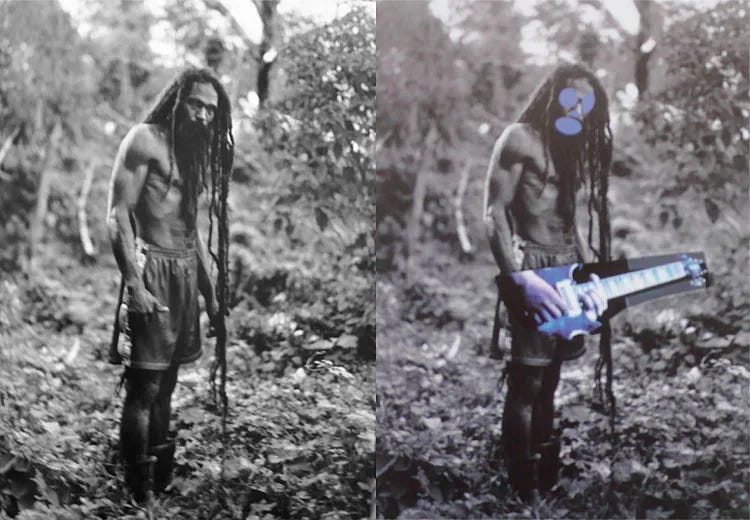

The genius of Prince's Cowboys is that many of the photographs he appropriated were made for Marlboro, a tobacco company whose product has led to the loss of millions of lives, including many cowboys. It's possible to imagine Richard Prince painted as being an Adbusters-style critic of the spectacle. However, his subsequent work, such as the photos of Rastas he appropriated/stole from Patrick Cariou and Donald Graham, shows no sign of political or artistic integrity. They are travesties.2

Prince says: “Basically I like the way things look; that’s all my decisions are about—if it looks good, it is good.”

The irony is that all this controversy makes the work more valuable. Indeed, it's difficult to imagine a successful artist who doesn't irritate the bourgeoisie. That's part of the job. The only thing that will stop Richard Prince is indifference.

Unfortunately, they are just too provocative not to discuss and raise questions about the notion of reproduction in an age of advertising that destroys our values. While talking to Rubin, Prince compared his work to New Wave punks with an intentionally amateurish approach to music. He used the camera as an "electronic scissor" to "sample" or "pirate" images. Prince has the freedom of the nihilist who exists in a world with few consequences. He is a mirror that reflects the emptiness in our culture.

The Golden Z (after Richard Prince)

Longtime readers may remember that this year I have been taking photos on Glasgow's Golden Z. After reading about Prince and listening to him on Rick Rubin, I thought it might be interesting to rephotograph all the adverts I saw.

While I don’t particularly like Prince's work, I sympathise with the idea once a photograph has been sold for an advert it is in the public domain. That is, if an image is forced on the consciousness of the pedestrian, I have the right to take revenge on that image by appropriating it.

Part of a series that gives credit to the original photographers.

What is especially galling for Cariou is how hard it was to get such photographs. As this blog comment says: "The people Cariou went to photograph for his book Yes Rasta are 'true,' as in very strict, Rastafarians living high up in the mountains of Jamaica. They are shy and it took Cariou quite some time and effort earning their trust. If you read the book you can see that one of the things they worried about was why Cariou photographed them and what was going to happen with those photographs."

<snap> https://whyweshould.substack.com/p/inappropriation </snap>

There's the work of Anastasia Semoilova who also uses massive billboards as backgrounds to surreal urban landscapes in her work. It fascinates me how and who is in charge of approving practices like this, taking someone else's work and turn it into your own and call it original art.

Great read Neil!