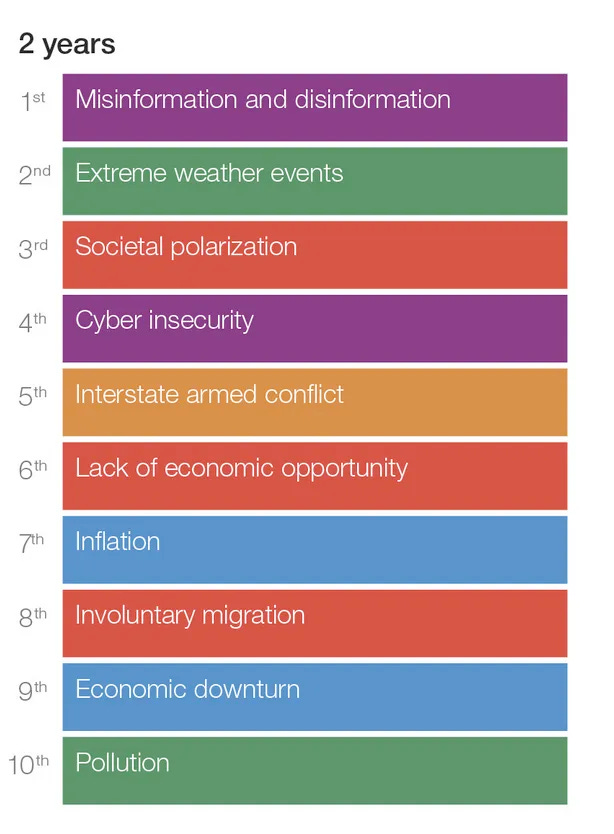

On 10 January, the World Economic Forum published its annual list of global risks. Misinformation, climate change, war, inflation—this is what we have to look forward to over the next couple of years.

I like that they made it a top ten … as if it were the pop charts. Now that music is less central, politics has become a way of identifying yourself. We all have our political affiliations—our pet issues—which help us to form alliances, much as Goths and Mods did with music.

While these political identities shape our personal top ten issues, we’re also swayed by whatever is happening in our lives. If you’re cold and hungry, you’re unlikely to have the capacity to worry about climate change. If you’re injured or sick, like I was this week, you might be consumed by the need for self-preservation. Maybe you have a deadline approaching. Maybe you have an obsession.

We are, though, still influenced by others, by news coverage, and by our high-status acquaintances. On Instagram, in particular, my friends have been posting relentlessly about the abysmal situation in Gaza. Every day they share speeches, interviews, war footage, protest dates, and information about who you can write to. I have been impressed by how practical they are. This is not shallow signalling but focused political action to try to stop the bloodshed. In a representative democracy, your options to influence are limited. A vote every five years in a first-past-the-post system seems laughably inadequate. I could write to my MP but she is already one of the most vocal supporters of the ceasefire so it’s hard to see what difference it would make.

Within our filter bubbles, it is easy to think that everyone is on the same page, but Google Trends reminds us that most people are thinking about sport and celebrities.

Even in a serious newspaper like The Guardian, the most viewed stories are pretty random.

To appeal to the public, news stories have to be novel while also fitting into pre-existing narratives. In this case, the top five could be filed under War, Ageing, Pandemic, History, and Brexit. Classic themes, and the same as the ones noted by the WEF.

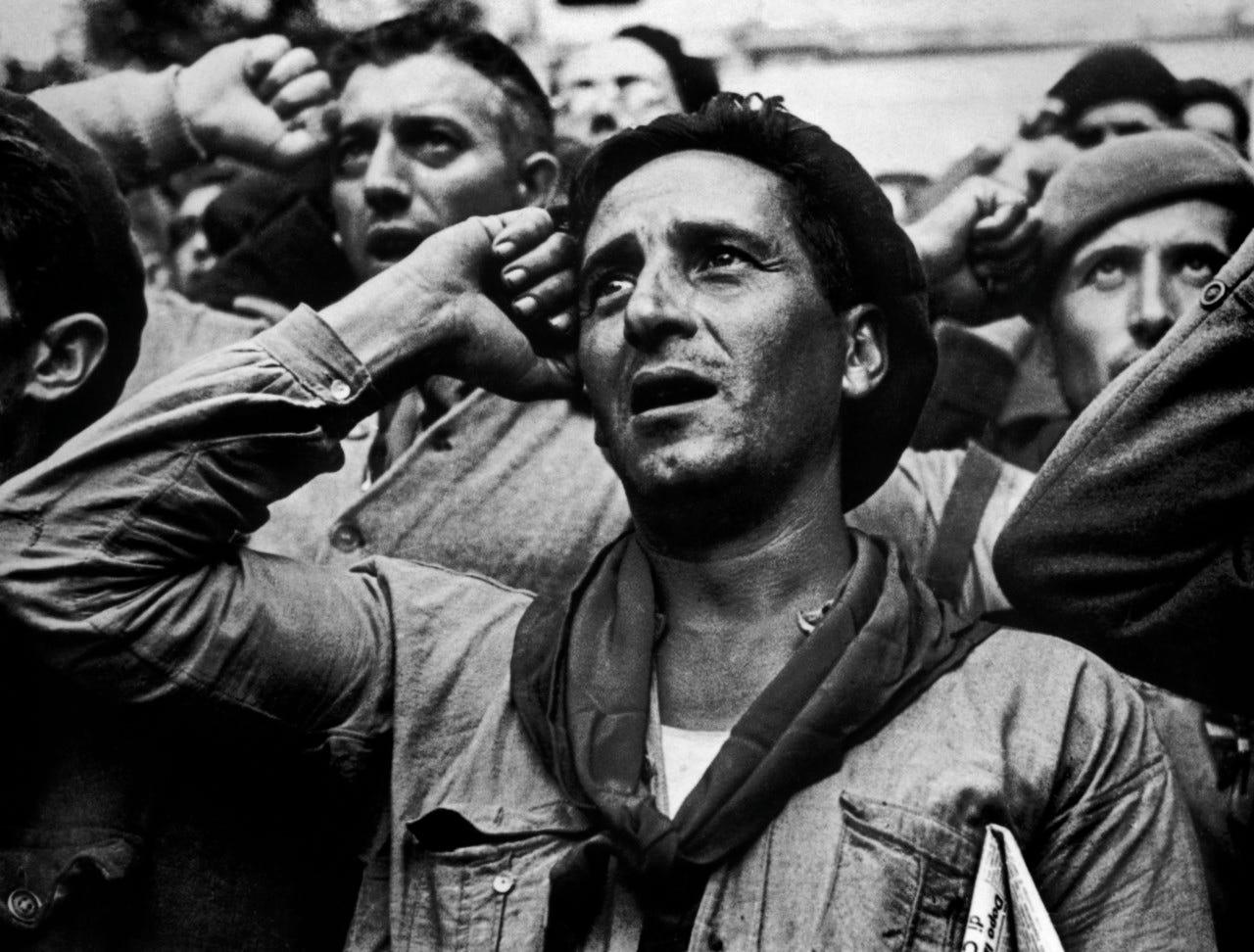

When it comes to photography, there is always a tension between the formal qualities of the image and the resonance of the subject. A bad photo of a world-historical figure will always garner more interest than a good photo of a nobody.1 In photojournalism, true greatness comes when the photographer consistently takes compelling images of momentous occasions.

Robert Capa (1913-54) was a genius photographer who basically invented modern war photography. He built his reputation documenting the Spanish Civil War, where he took this controversial—possibly faked—photograph of the falling republican soldier.

Capa was friends with Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck. He was the lover of Ingrid Bergman. He was a heroic figure who spent his professional life as a war photographer, covering the most important historical battles of the mid-twentieth century.

He was, for instance, the only civilian photographer to cover the D-Day landings on Omaha Beach. His blurry images, only eleven of which survive, give a sense of the drama of that day.

He captured iconic images of Germans surrendering:

French women being shamed for collaborating with Nazis.

And the dead body of the “last man to die” in WW2:

After the war, Capa went to the Soviet Union, Imperial Japan, newly established Israel in 1948,2 and Vietnam in 1954 where he died after standing on a land mine. His photographs have an immediacy that makes them feel fresh even now.

It is impossible to do the kind of work Capa did when the conflict consists of firing 2,000-pound bombs on a city. The resulting images tend not to show soldiers, just rubble and bleeding toddlers. Despite Israeli attempts to shut down communication, Gazan photojournalists and citizens have been sharing images online. It is important not to look away.

If you want to read more about war photography, I highly recommend the Substack of

.The photographs in this article are used for criticism and review under the Fair Dealing provision of UK Copyright Law. All rights to the image remain with the photographer/copyright holder. This use does not claim any rights to the original work and is not for commercial purposes.

For some, his images worked as unofficial propaganda, helping to erase Palestinians.

Very thought provoking, as usual! Your range of knowledge amazes me!

Appreciate the shoutout. Nice work.