While protest movements often fail to achieve their primary goals (e.g. CND, Anti-Iraq War, Occupy, BLM), the secondary effects can have huge consequences. Take Occupy. A generation of leftists found purpose amid the encampments, galvanising a populist movement that nearly led to Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders getting elected.

The war in Gaza—and its ensuing protest movement—now dominates the thoughts of millions. Overnight, my friends’ Instagram stories stopped being about their social lives and became a succession of news footage, fundraisers, speeches, death counts, reading lists, and demonstration dates.

I fully support the call for a ceasefire but worry that Instagram is an inadequate tool to achieve this end. Nonetheless, it has been fascinating to see people being educated in real-time, with previously obscure terms like Nakba and settler colonialism becoming ubiquitous within days.

The concept my friends have been sharing that I predict will have the most far-reaching consequences is decolonisation. It is not a new term—Wikipedia traces similar ideas back to Thucydides—but the intensity with which it is currently being discussed feels significant. The word has gone from being a simple description of post-imperial policies to a metaphysical demand.

In the visual arts, narratives around decolonisation are everywhere. The world’s most prestigious art exhibition, the Venice Biennale, is leading the way with its show Foreigners Everywhere. Pierre d’Alancaisez complained that this year's Biennale demonstrated a "nearly complete abdication of aesthetic criteria in favour of a decolonial organising principle".1

Ever since Marcel Duchamp rejected retinal art in favour of art that serves the mind, artists have been gazing inward. Unfortunately, what they found in there was a warehouse of imperial spoils: science, humanism, modernity, and progress. All of these ideas are being called into question, with academics and others working to:

Despite this expansive use of the term, prominent academics in the field insist that decolonisation is not a metaphor. In this, they are drawing on the work of Frantz Fanon, the Marxist psychiatrist from Martinique, who helped Algerians overthrow French rule.

Fanon has become a saintly figure for activists (he died of leukaemia aged 36) and is often quoted to justify violence. In The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon writes that "decolonisation is always a violent event":

The starving peasant, outside the class system, is the first among the exploited to discover that only violence pays. For him there is no compromise, no possible coming to terms; colonisation and decolonisation is simply a question of relative strength.

The 7 October attacks by Hamas were seen by many as a part of a decolonial struggle of Palestinians against Israel, with Fanonian violence considered a necessary path to liberation. Others, like Zadie Smith,2 prefer to see Fanon as a visionary utopian:

The dream of Frantz Fanon was not the replacement of one unjust power with another unjust power; it was a revolutionary humanism, neither assimilationist nor supremacist, in which the Manichaean logic of dominant/submissive as it applies to people is finally and completely dismantled, and the right of every being to its dignity is recognised. That is decolonisation.

In both cases, the overarching goal of decolonisation is a transformation of everything we know. It's all tainted: from capitalism to the language we speak. As the activists behind Rhodes Must Fall write, "the structures of knowledge production [...] continue to mould a colonial mindset that dominates our present."

As a Marxist and a Freudian, Fanon knew that we are not fully intentional beings. We are bound by hegemonic forces, unconscious forces, and economic forces. The individual struggles to escape their biases, so decolonisation must take place on a structural level. What matters is not your corporate DEI initiatives, but who holds power.

The problem with this approach comes when one tries to imagine how power would be transferred to those who believe the foundation of that power—the institutions, the economic system, the science—is illegitimate.

Decolonialists talk about indigenous rights, but the indigenous populations of the planet are often helpless against the threat of disease, technology, and pollution. Only a conscious, determined effort to leave them isolated can prevent their destruction. Where then does isolationism leave the collective response to things like climate change?

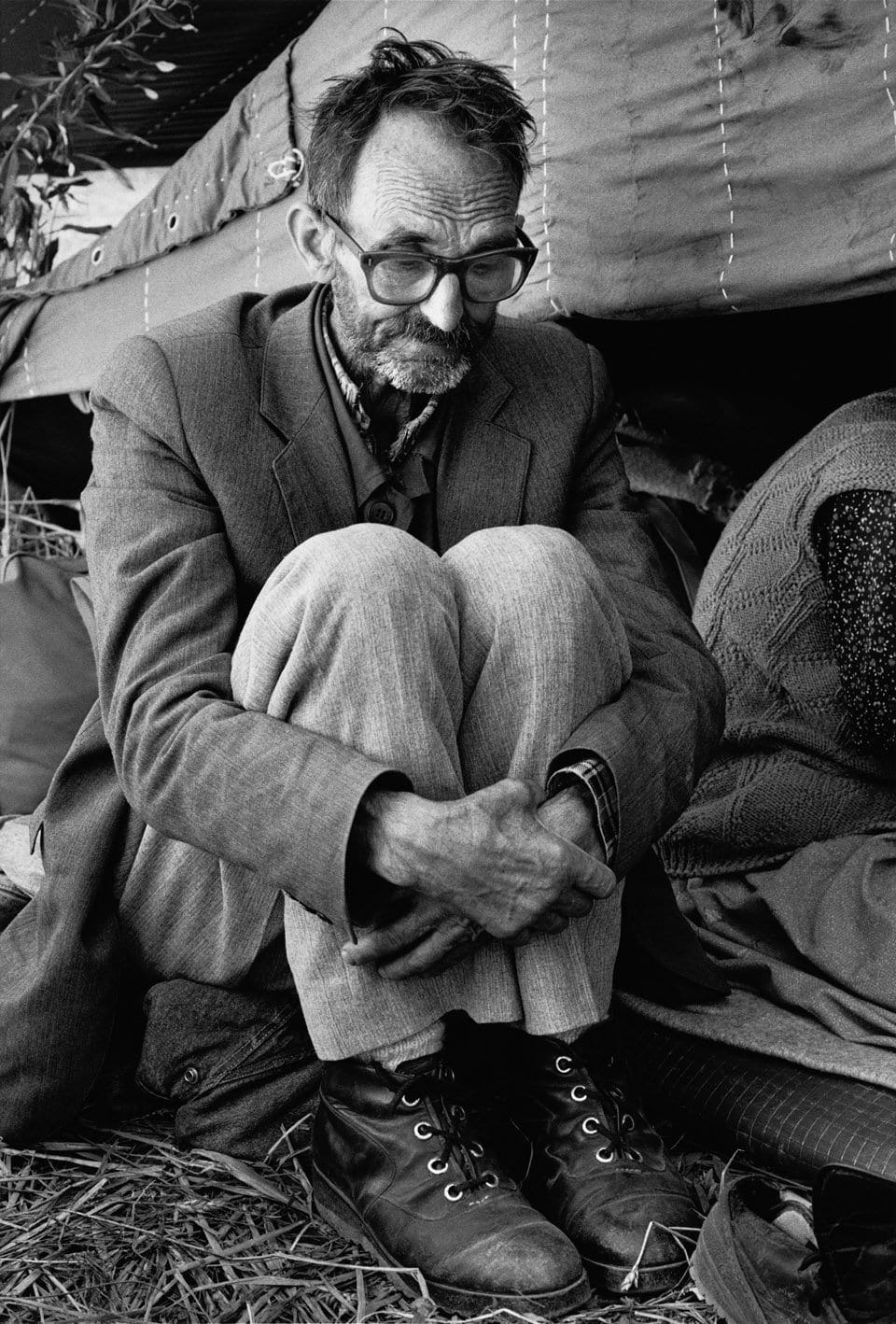

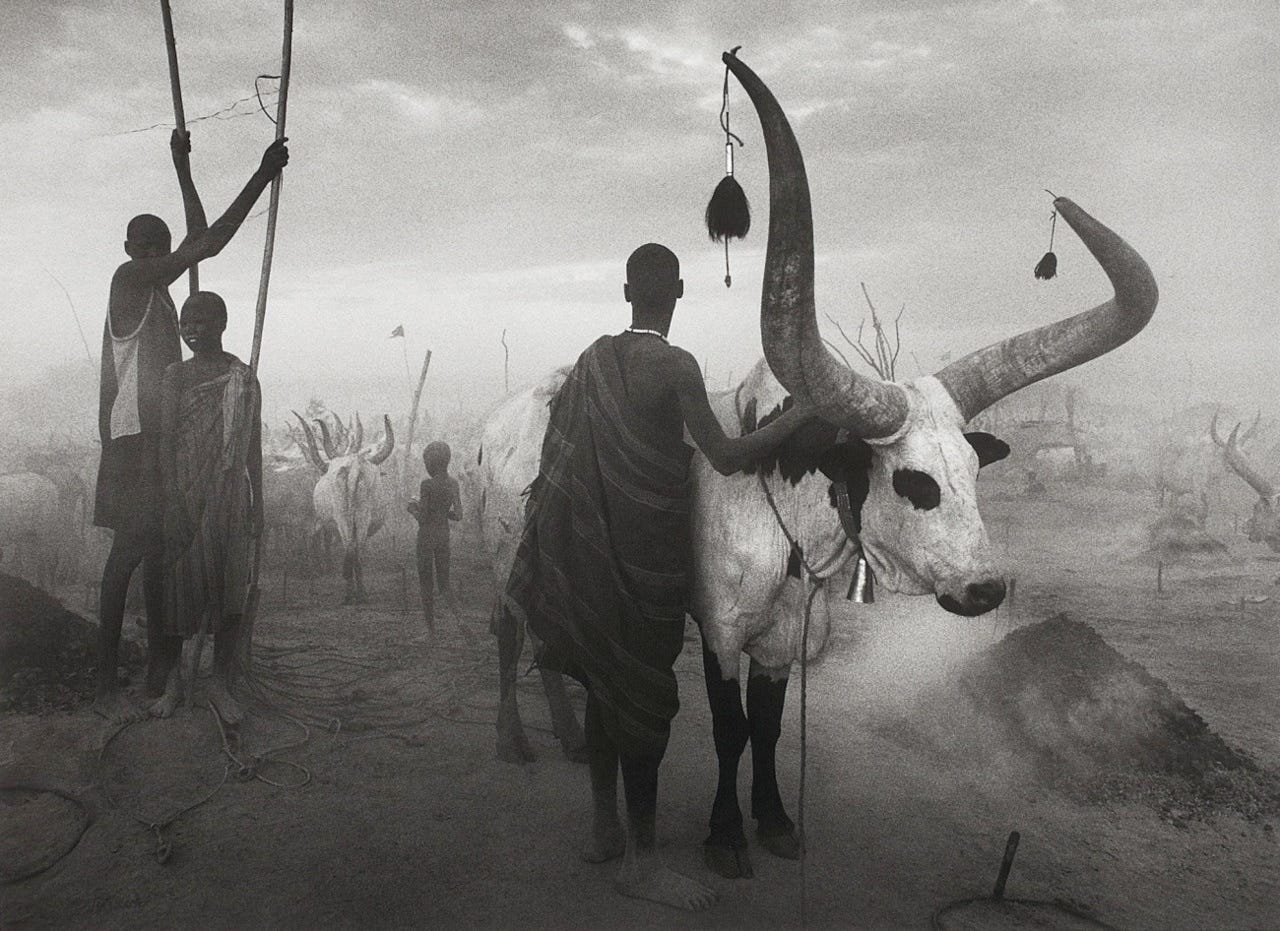

One person who has engaged with these questions is Sebastião Salgado, perhaps the greatest photographer of the indigenous and dispossessed. His immense documentary projects present the diversity of the human race but offer a vision of global solidarity. He writes:

I feel that the human race is one. There are differences of colour, language, culture and opportunities, but people’s feelings and reactions are alike.3

Salgado is from Brazil, a country almost too big to be fully colonised, where even now dozens of tribes remain uncontacted. His photographs give us an insight into the strangeness of human arrangements, a last glimpse of innocence before they are consumed by Moloch.

There have been a few accusations that he exoticises his subjects, much like the Orientalists, but most see him as part of a politically committed, humanist tradition of photojournalism. His camera looks into people's eyes, the portals to our suffering, and finds the universal.

However, Salgado doesn't just focus on individuals and their suffering. The photograph of the Serra Pelada gold mine is the most immense study of human industry I’ve ever seen. It’s like the Tower of Babel or Dante’s Inferno.

For the writing of this piece, I consulted his huge photobooks: Genesis, Workers, and Migrations. All three show a different aspect of the human experience—nature, capitalism, and war—but, in each of them, we are a small cog in the machine. I am reminded that Salgado trained as an economist and sees the world with a macroeconomic God's eye view.

The critic Julian Stallabrass agrees:

Salgado is dangerous because [...] he begins to reveal an image of the operation of global capital—seeing it as a single system with its components, human and mechanical.

But what are we to do with these insights? What do they offer those who see injustice in the world and are determined to decolonise?

Susan Sontag wasn't convinced they helped solve global problems. In Regarding the Pain of Others she argues that the photographs "may spur people to feel they ought to 'care' more." But:

[They] also invite them to feel that the sufferings and misfortunes are too vast, too irrevocable, too epic to be much changed by any local political intervention.

Sontag was active at a time when revolutions could still happen. Nowadays they feel unimaginable. The machinery of globalisation grinds on and all we can do is watch.

Unlike Occupy—now 12 years ago—there is little optimism in the pro-Palestine protests. There is, however, a determination to force those in power out of a colonial mindset. Perhaps the first step in shifting that mindset is to empathise with different perspectives; Salgado's photographs help do just that.

As I write, Smith is being widely criticised for a recent New Yorker essay on language used in describing the war/genocide/onslaught in Palestine.

From Migrations.

I appreciate the breadth of this essay quite a bit. It's thoughtful, analytical, incisive. It's a rare kind of read amongst fellow photographers. So I'm hesitating to criticize it, because I would personally like more of this type of marriage between photography and deep social analysis. Patrick Witty offers some in his posts on war photography, and we occasionally see posts about the WPA photographers, protest photographers, poverty and so on, but they tend to be general overviews. Very few with your level of philosophical context and analysis. But in the end, I think the essay is misguided.

What I mean specifically is that while I think the campus protests and your friends' IG feeds may have been a trigger to your thoughts on colonization, ultimately I don't think that subject fits with the Salgado you present here. I mean to say, it possibly could, but you talk about the breadth of his work as being "humanistic", and you bring up several powerful visual examples of his stance for the dispossessed, the primitive and the exploited, but not exclusively about his work within colonial power structures. For the most part, the examples in the essay aren't related directly to colonial subjugation: we see images of ethnic wars in some; outright capitalist exploitation (near slavery) in others; climate change in still others. I suppose one could argue that the exploitation Salgado represents all starts with the colonial mindset, but then again, someone else could argue with equal vigor that it starts with the capitalist mindset, or the racist mindset, or the mindset one gains from not accepting Jesus as one's savior, and so on.

And by leading with the campus protests and the philosophical underpinning of colonialism, you've opened your argument up to a significant sidebar on the question of colonization vis-a-vis Israel -- a debate that hasn't been reconciled in over 75 years and won't be by any single essay any of us here on Substack (or anywhere) can write. But it unfortunately leads to discussions that are removed from Salgado and the power of his work. That, in the end, is what I think is the problem; the essay is textually about a subject which Salgado only partially addresses in his many decades of work. If the examples and discussion on Salgado focused on his work, say, in former Portuguese or British colonies, the essay could succeed. But showing Salgado to be a photographer of the commonality of humanity while isolating colonialism as your single point of argument, I think, suggests you have two separate essays here.

So much in this piece, Neil: each “section” the germ of much longer discussions. The politics of language and representation are fraught and complex, especially when the suffering of so many is so great and so obvious. I have gone to Salgado, over the years, for the humanity and compassion of his eye. Everything is political and it’s Salgado’s fundamental relational disposition that moves beyond rhetoric and partisanship. I never get the sense that he begins from an ideological position. Does he exoticize his subjects? Or does he underline the obscenity of our “systems” in the face of human and planetary suffering?

Thank you for this post!