There is an idea in anthropology that societies can be divided into shame cultures and guilt cultures. Shame cultures enforce morality by publicly chastising people who have committed a crime, whereas guilt cultures internalise punishment, making you feel bad, even if there is no chance of getting caught.

In the social media era, it seems that we are moving away from guilt and towards public shaming. I lament this development. With a guilt culture there is a chance that people can be redeemed if they learn from their mistakes, show contrition, and make amends. With a shame culture, once you're out, you're out.

Since writing about Effective Altruism I have been questioning my own behaviour. Am I a good person? What does that even mean? I don't beat up old women, but neither do I spend much time helping them cross the road or ensuring their grandchildren don’t die of preventable diseases. It feels as though, in the absence of an almighty judge, effective altruism is an attempt to prove your goodness through metrics like lives saved.

What I do have is a conscience, often a guilty conscience. Those memories of times I’ve transgressed ethical boundaries haunt me at random moments. The scene will pop up in my mind when I’m in the shower and make me cringe. I try not to turn away from these and integrate them as much as I can, but these are ethical intuitions that have been instilled over thousands of years to help regulate civilization so they are not going away any time soon.

One memory that often gets repeated is when I was taking photos in Laura's Gran's farmhouse. The old ladies were playing cards and there was one woman who had this amazing, ancient face, full of lines and experience. As she was chatting with her friends, I decided to take a photo of her. I didn’t ask for permission, but I took the photo anyway. What I didn't realise was that my camera emits a light if the room is too dark in order to assess how much to open the aperture. She saw this, turned to me, and managed to communicate, despite my squirming embarrassment, that I was welcome to take the photo. She didn’t call me out, but she didn’t need to. This was a violation of her personal space and her dignity. What right did I have to take the photo of her in a private moment? How would I like it if someone started examining me like a lab specimen?

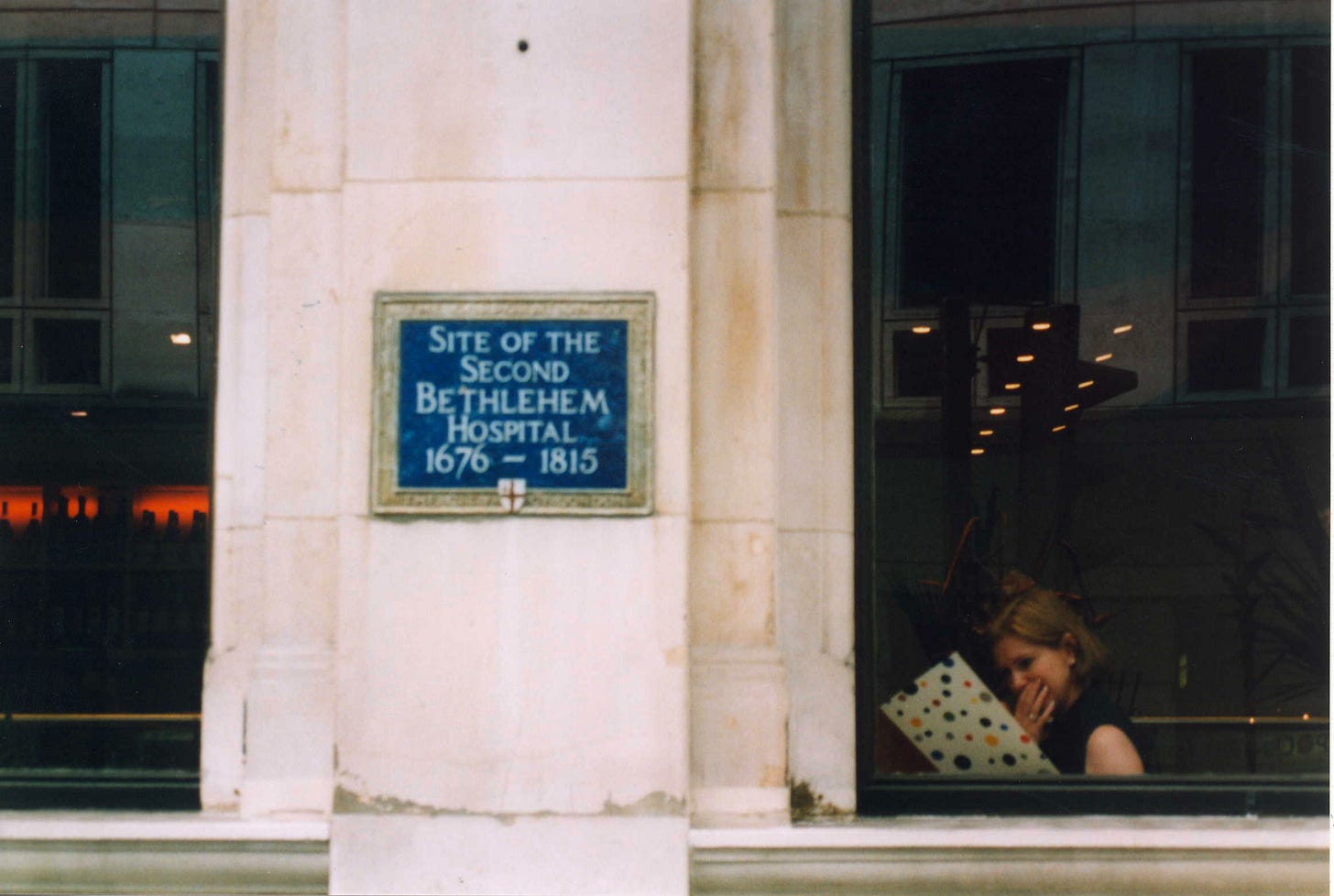

I got into photography in 2003 with the first cheap compact digital cameras. We had a Fuji F410 which was was tiny but produced what seemed, at the time, high-quality images. I'd walk around London and take photos of things I thought were interesting:

I didn't know what street photography was, but it felt like I was capturing real life. I kept my eyes open and took lots of photos, freed from the costs of film. It didn’t really occur to me that I had an ethical relationship to my subjects, although I was conscious that I didn’t want to get caught.

Photography is the pre-eminent artistic medium of the talentless. When Brooklyn Beckham wanted to be taken seriously he released a book of blurry photos. It is the art that most displays the Dunning-Kruger effect, the idea that the less you know, the more confident you are about your abilities. After all, even a monkey can take an incredible photo.

The difference between a monkey and a great artist is one thing: consistency. Your photographs must have a consistent quality that makes the audience trust your intentions. Consistency comes from an ability to curate the infinte photos you can take and turn them into a convincing aesthetic experience.

Martin Parr is exemplary in this respect and the only photographer whose work always stops me mid-scroll.

In Parr‘s photos there is a uncanny normality that is brought to life by the vivid colours and expressiveness of his subjects.

When I look at his photos I think about how photographs can transcend the individual and catch the zeitgeist in all its banality. I never feel like he is being obnoxious or ethically dubious. Nevertheless, Parr rarely asks permission:

"Sometimes people object: that’s an occupational hazard. I accept that all photography is voyeuristic and exploitative, and obviously, I live with my own guilt and conscience."

I used to think that you should take any photo as long as the resulting image is beautiful or captures something of the human spirit. It's a utilitarian calculus: the greatest happiness of the greatest number over the dignity of an individual. These days, I am not so sure.

My ethics are the golden rule of ‘do to others as you would be done to.’ Fortunately, I am not a sadist or a masochist, so that shouldn’t mean inflicting pain on people, but the ethical calculus alters if you extrapolate and imagine the world if everyone started doing street photography. Life would be very depressing and there would be no privacy. We are already surveilled by millions of cameras and websites, who needs more Stasi volunteers gathering evidence in the hope of getting likes?

One of the best street photographers of the twentieth century solved this dilemma by never printing her images. Vivian Maier took thousands of photos but, because of her awkwardness, kept all the rolls stored in a chest. These were discovered a few years ago and she became famous after her death. All her intimate photographs were relieved of ethical concern because they emerged fifty years after they were taken. Surely no one can object to a photo after so many years.

Maybe this is the perfect compromise: take a photo of anything but there is a 30 year publication gap, like the Official Secrets Act.

The Glasgow Gallery of Photography has as a rule not to accept any photos of homeless people. Partly because it is such a cliché of street photography but mainly because they are demeaning. Anyone in a public space can be photographed, but homeless people don't have the choice not to be in public. The gallery might tweak this rule if the photographer was homeless themselves or the photo depicts the subject in a new and unusual situation. What they won’t accept is the kind of images that Henry Oliver1 took in Westminster where he just stood over a homeless person and took a photo.

Looking through my archives, I thought I would find some photos of homeless people, but apparently I've always resisted. I prefer it when people are proud to be on display, like at an Orange March.

There is a valid concern for protecting children, who can’t object to their upbringing, but over a decade has passed since this photo so I think it is just about acceptable.

Or these photos of people watching Drakes of Hazzard at the Glasgow Fair, again from a decade ago. Individuals come across as members of a collective.

Compare that to this mother who doesn’t have enough hands to look after her children and her ice cream. It creates a funny image, but I’m not sure I would be able to defend it if she objected.

The joy of street photography is that it allows you to see things anew, making you more aware of reality as it is. The intentions of the photographer are important, but so are the intentions of the viewer.

Part of the pleasure as a viewer is imagining how brave the photographer is to risk taking the shot. I’ve been enjoying the fresh, raw photos of Steve J McQueen, a Glasgow artist who is pretty fearless:

Such photos haven’t come without incident, as McQueen told me:

I have had various confrontations including a particularly vivid one when a guy had me by the throat and was threatening to kill me. That particular incident was avoidable on my part, I was too brazen, too confident and ignored fairly obvious signs of potential trouble. So I hopefully learn from such incidents.

McQueen also mentioned the gallusness of Dougie Wallace aka Glasweegee:

This is social documentary, but it might as well be from a warzone. The original Weegee is tame by comparison.

Just as there are some thoughts that inspire people to start writing, so there are some situations that inspire them to take a photo. For most people, that moment is socially conditioned: we take photos of tourist attractions, family gatherings, and situations that broadcast the 'right' signals. It takes a special person to want to become a street photographer and capture the ugly truth. Their idea of the photographic moment is more complex: it could be banal or shocking, it just needs to pique the interest and arrest the eye.

What do you think? Would you take such photos?

The photographs in this article are used for criticism and review under the Fair Dealing provision of UK Copyright Law. All rights to the image remain with the photographer/copyright holder. This use does not claim any rights to the original work and is not for commercial purposes.

I didn’t really known who Henry Oliver was except that he is, like me, a big fan of Dr Johnson. It turns out he is also a former researcher for Liz Truss.

I think the photos you take on the street will reflect the kind of person you are. If you are a respectful person, that will come across in how you choose to photograph people and what you choose to publish. If you're not a respectful person no amount of criticism or advice will help. As our societies give the appearance of becoming less respectful or considerate, while also becoming more aggressive and confrontational it is more or less inevitable that street photography will move in the same direction.

As an anthroplogist, we have a code of professional ethics around representation, consent etc. I've often been amazed when collaborating with artists (have collabed with people using sketching, live art) or journalists around how little thought is given to that aspect. Fiction writers, too, sometimes chat about how they eavesdrop in public spaces. It's interesting - at last! - to see a post that picks this issue up. Naive question: is there any kind of professional body for pro photographers with a voluntary code of ethics? Lemme drop the link here to anthro examples of ethical codes. (Standard across all of academia to have a code of ethics. You can't apply for any research money without submitting your plans for scrutiny by an ethics committee. This is just banal normal process).