The Photobook of the Film

A review of Patrick Keiller's London (1994) and London (2020) by Patrick Keiller

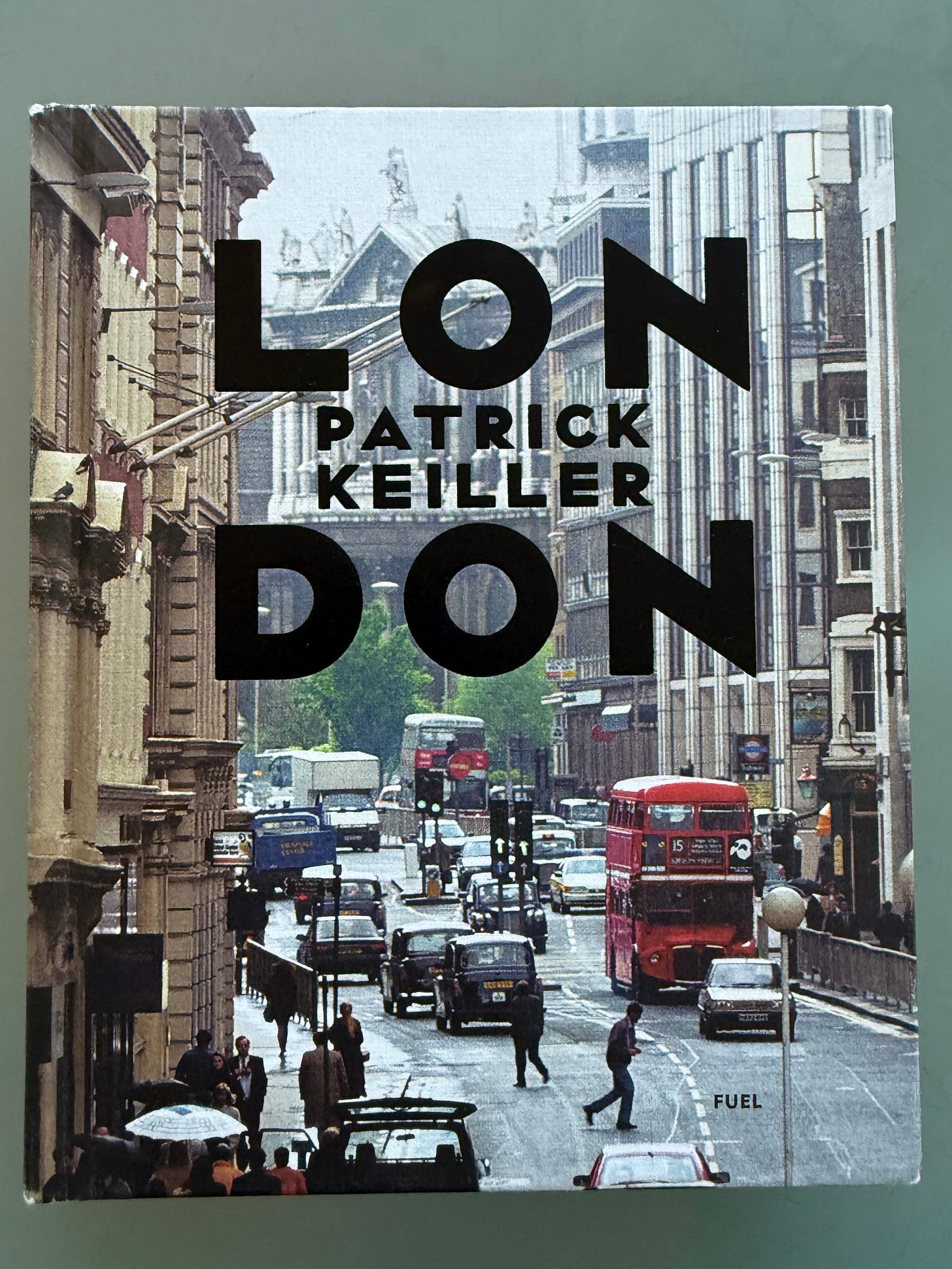

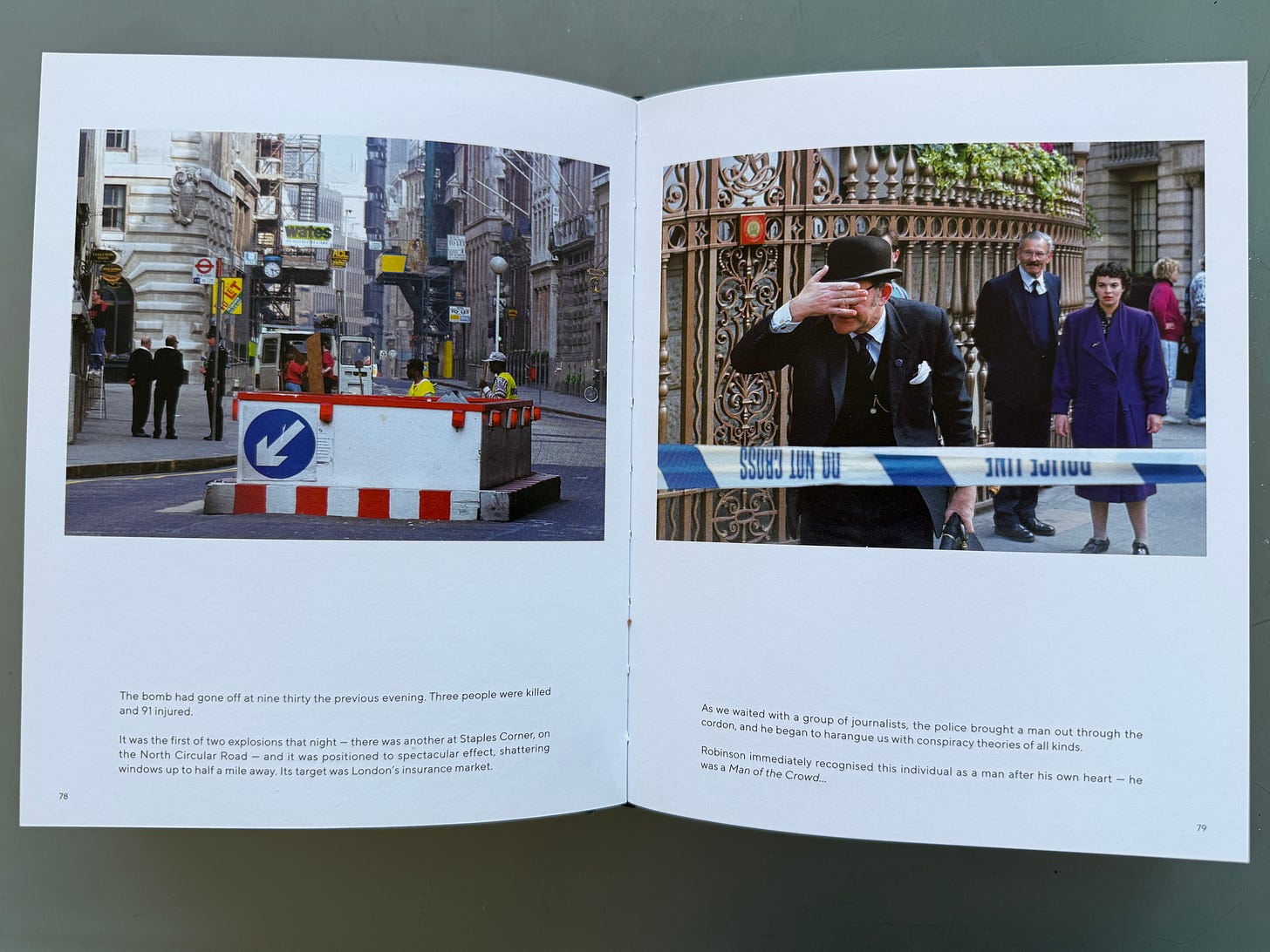

Patrick Keiller's London (1994) is the closest that cinema gets to photography without using still images. All the footage is taken with a static camera placed on a tripod that records whatever is in the frame for 10-40 seconds, while an off-camera narrator talks about a protagonist we never see. The film lingers on urban scenes in a way that resembles street photography but with the people actually moving.

Here’s an excerpt:

The first time I saw London was a revelation. It was unlike anything I had seen before. I watched it with the ecstatic pleasure of an obsessive identifying their obsession. In this case, the obsession is psychogeography, that strange alchemy of place, history, and psychology.

I was living in London, working in a public library, publishing a zine, and taking hundreds of photos. Thanks to the curiosity of people like

, Matt Haynes & (who wrote Smoke), and Iain Sinclair, the city was alive with stories. Keiller's London, however, was the brightest star in this constellation and inspired me to see the world anew.1Psychogeography has, it seems, fallen off the cultural radar. It was part of the decadence of the post-modern malaise that came when people thought history had ended. The ideological solutions to society’s problems had failed—what else could we do but examine the discarded fragments?

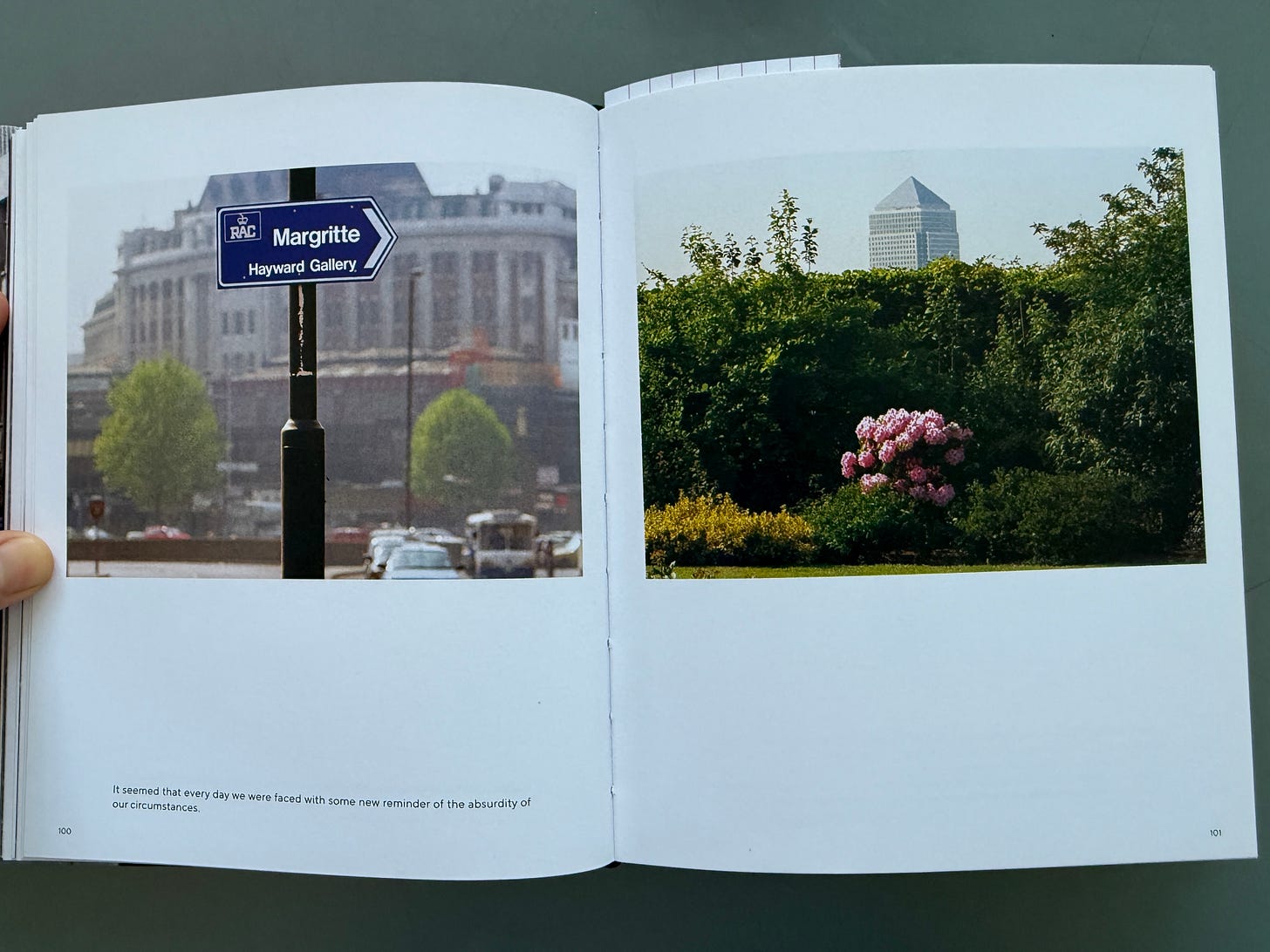

It’s common nowadays to use the term "ADHD brain" to describe someone whose mind is beset by disparate connections and scattered references. But back then we didn't have words for the allusiveness that we get in Keiller’s London. The film stretches into the deep history of Roman London, it wrestles with the English Revolution, and it has dalliances with various French connections. While it comes to no clear conclusions it does give the breathless vertigo of great art.

Part documentary, part fever dream, London wears all its strange innovations lightly. Keiller had been working in academia and filmmaking was a sideline rather than an end in itself. His earlier films, such as Stonebridge Park (1981) and Norwood (1983), are similarly deranged experiments in fictive urbanism, but none have the visual purity and narrative inspiration of London.

It is a film that repays endless rewatches, so you can imagine how delighted I was when Fuel Design (better known for coffee table books on Russian criminal tattoos) published a photobook of the film in 2020.

London is perhaps the most apt film to be turned into a photobook except for Chris Marker’s La Jetée, which is literally made of static images. Even so, something about it doesn’t quite work. In the film, there is a meditative feeling, alongside the arch narration of Paul Scofield. The book, by contrast, invites flicking back and forth.

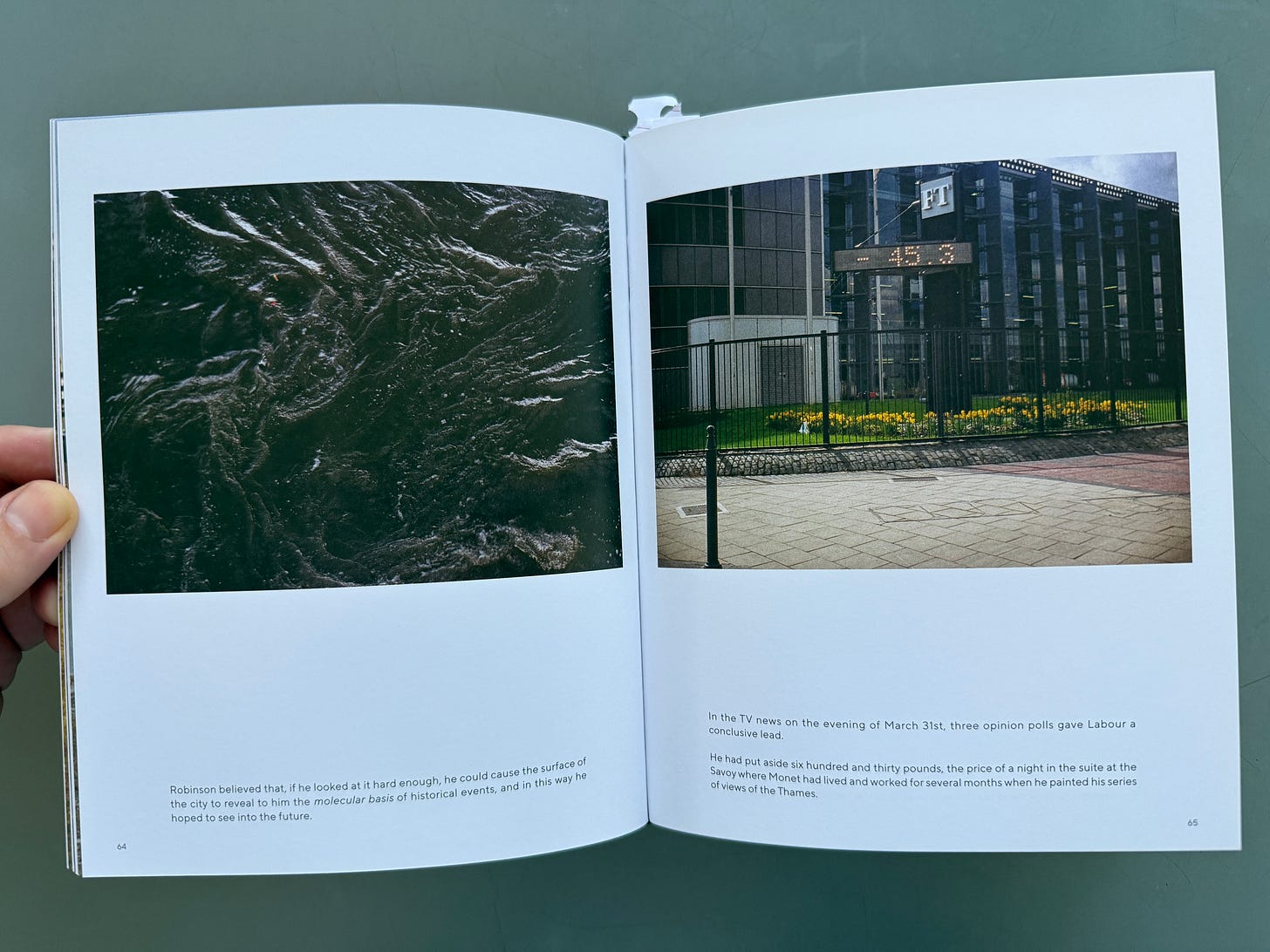

At its best, photography can stimulate movement in the mind of the viewer (see Robert Frank’s The Americans). But here, by choosing one frame of film, we get the reverse: it freezes the film and renders it lifeless.

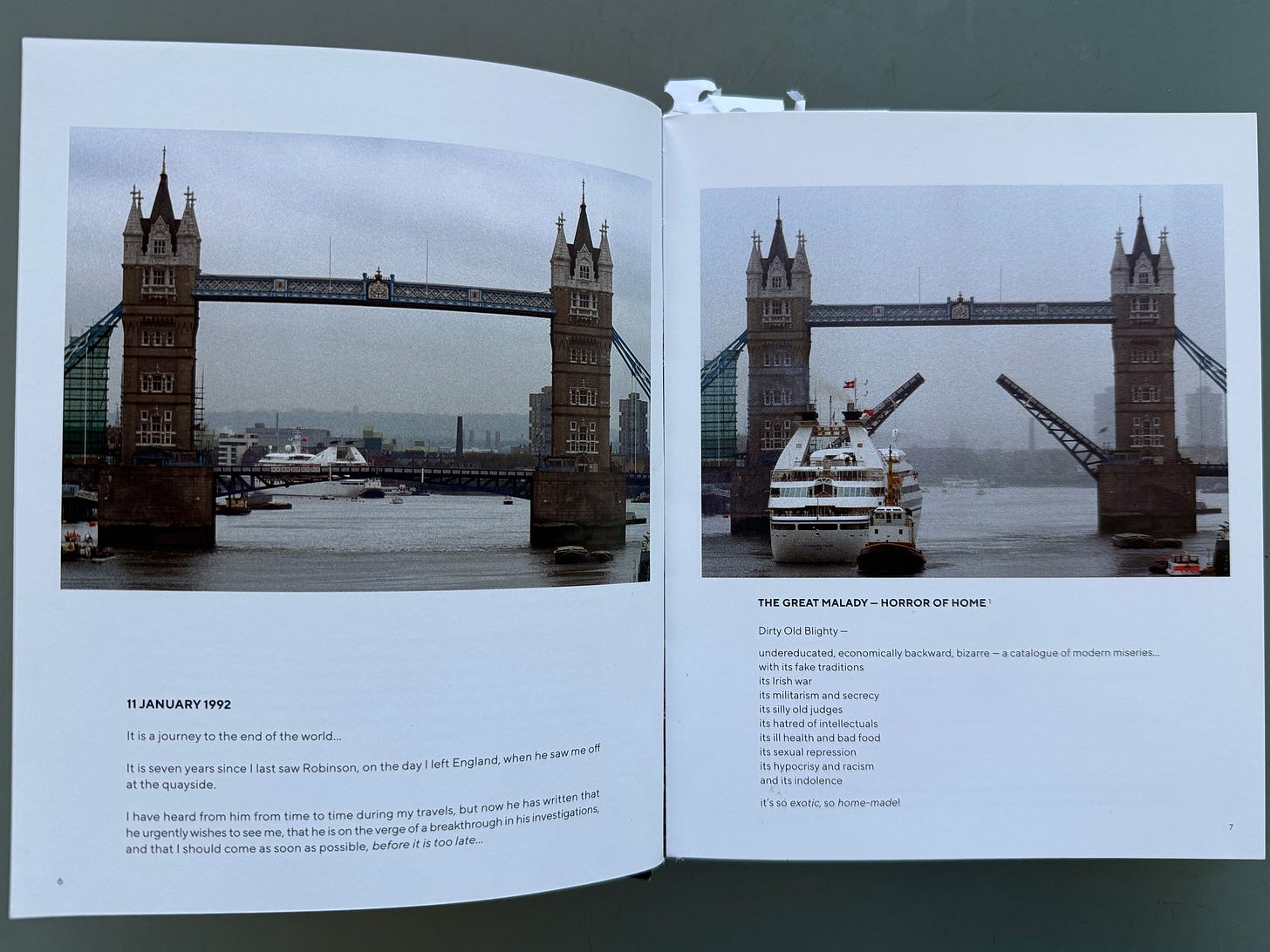

The “photos” are shown with the accompanying narration set down as paragraphs. You can thus play the film in your head. I find it hard to imagine anyone who hasn’t seen the film getting much from the juxtapositions.

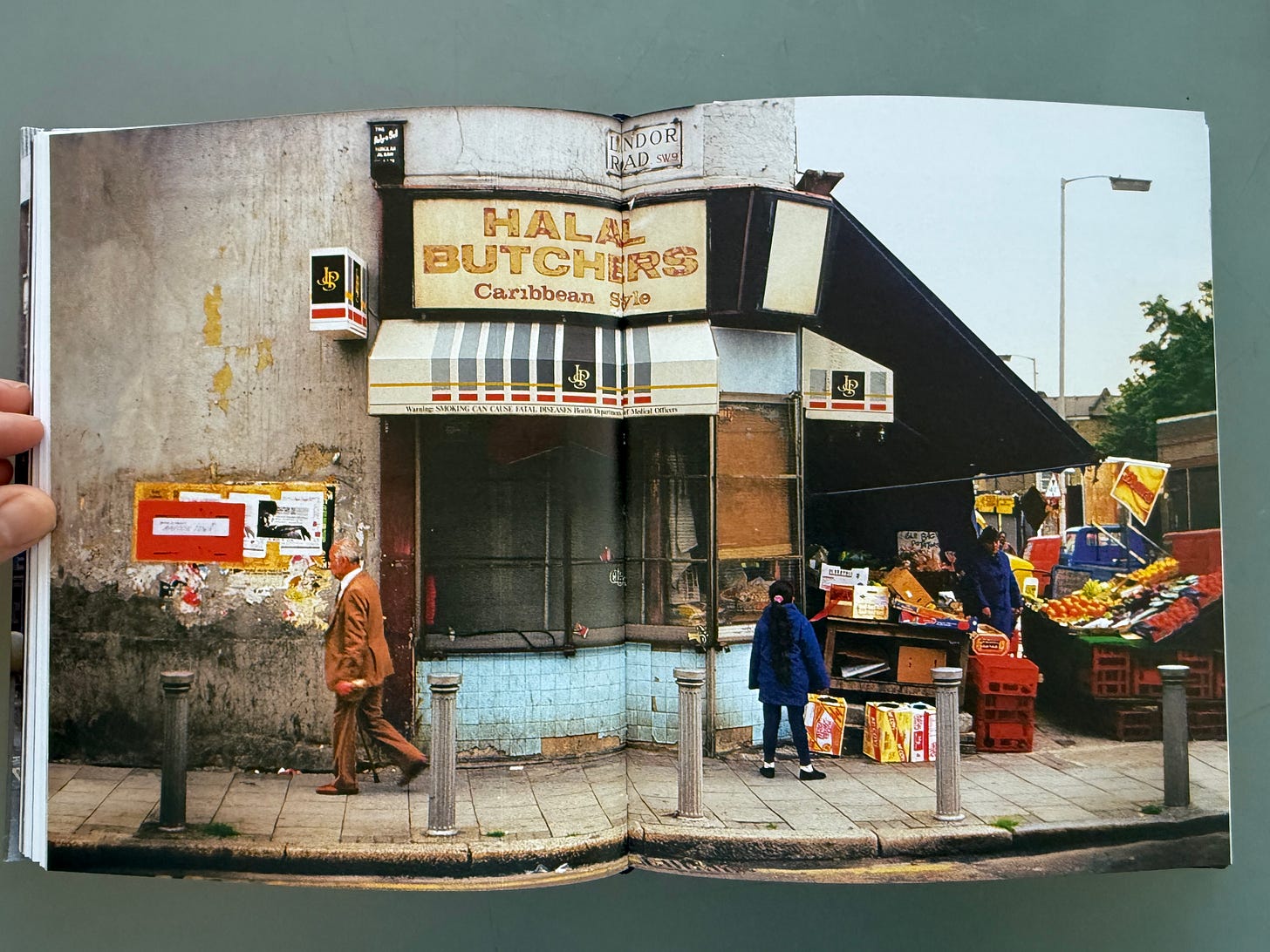

The inclusion of the narration also undermines the sense of the images as photography. On the rare occasions when there is a full-page spread, it is actually quite compelling. I love this colourful “photo” of a Halal Butcher (Caribbean Style) with a cigarette logo which is like a precursor to Yookay Aesthetics.2

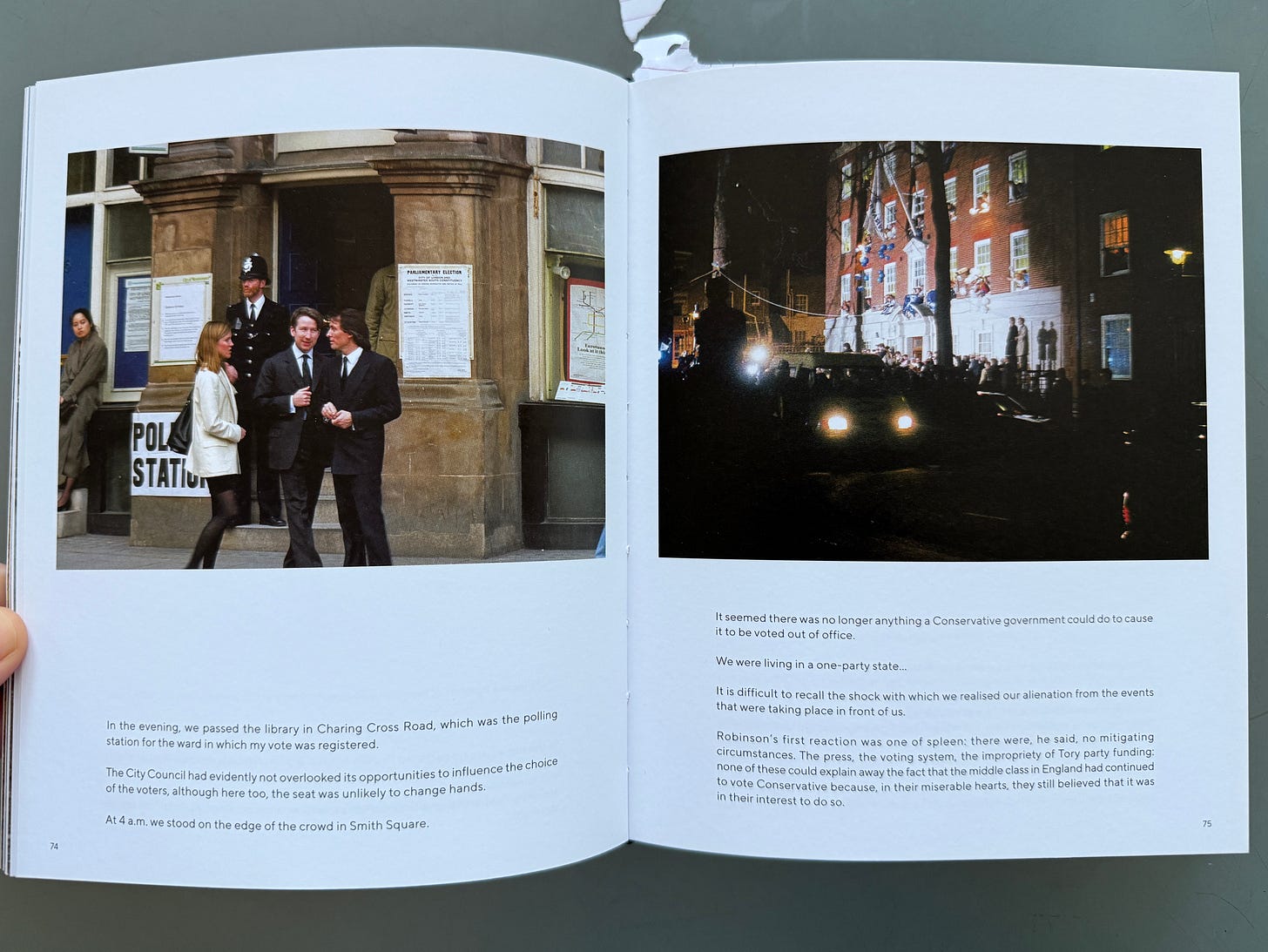

London is set in the election year of 1992, a time when Margaret Thatcher still haunted the country. There was widespread expectation that John Major would lose the election, but thanks partly to The Sun newspaper, he retained power.

Like so many novelisations, this photobook is more of a curiosity for the obsessed rather than a work of art in itself. However, I highly recommend you watch the film (and its sequel Robinson in Space) if you get the chance.

Bonus content!

Inspired by London and a walk I did with

, here is a short film I made that mimics many of Patrick Keiller’s tropes.Writing about Keiller reminded me of a classic piece of ‘copypasta’, which is about 50% of a description of me. Thanks to quizzing Michael Oswell and Anindya Bhattacharyya, I discovered this was by Hannah Proctor. Here it is for posterity:

They were born in the early 80s. They went to an elite university but not to Oxbridge. They have some potted plants and like to cook from recipe books - probably they have the first Ottolenghi book but they know that's a bit passé now. They don't go out much anymore but they still check Resident Advisor from time to time because they like to think they could go out if they felt like it. Sometimes they go to Café Oto. They were probably into Burial at some point. They also have a favourite Mahler symphony. They've probably been to Berghain and even considered moving to Berlin in the mid-2000s. They used to stay out till dawn dancing in warehouses in Hackney Wick. Now they have a stable routine. They watch Adam Curtis documentaries to keep up with the sneery conversations on Facebook and of course Chris Morris and Patrick Keiller were always their heroes. They could make a joke about the Werner Herzog penguin documentary. They are left-wing but they would never use embarrassing words like 'solidarity' or 'comrade'. They rarely, if ever, go to protests. They have a job that requires them to wear clothes that are relatively smart - a round-necked woollen jumper over a shirt, for example. They have a pure wool scarf and good leather shoes. They do not read Marx but they know enough about him to make fun of people who are obsessed with the value form. Their group of friends from university who they see less and less don't know anything about the value form though. They might own a copy of A Thousand Plateaus but it's years since they bothered reading that kind of thing. They like Jonathan Meades and Stewart Lee. They hate Clapham even though one of their friends moved down there recently. They read the Guardian online but of course they know it's shit. Sometimes they read articles on Jacobin. They have a long-term girlfriend but feel weird about getting married even though they've already bought some second-hand teak furniture together and various kitchen appliances. Probably they have lived in Stoke Newington at some point but probably they don't anymore. Probably they would go to a gastro pub from time to time but they would probably call the other people in it 'cunts'. Probably they have a decent coffee maker of some sort. They are not egregiously misogynistic but they probably do not read many books by women. They have a degree of success in their field. Over 3000 followers on Twitter. They are not rich and still have to juggle various jobs - some freelance, some not. They get very angry about the state of the world and remember weird details about the machinations of the Parliamentary Labour Party. They probably subscribe to the London Review of Books. They probably read novels and non-fiction hardbacks but not as much as they did in their early 20s when they got really into Pynchon. Of course as a teenager they really liked Ballard. They'd definitely recognise Ian Sinclair if they saw him on the street but they don't go to Dalston so much these days.

Very interesting & thought provoking article.

Loved your film about Glasgow. It made me think about what has happened to all the other British cities which prospered in the days of Empire.

Glasgow seems to have had a worse outcome, compared to cities like Bristol, Manchester and Liverpool. If this is true, why?

Thanks for this Neil. Patrick keilers London film is truly a quiet and poetic work of art that on seeing if for the first time whist living in London in the 90s was indeed a revelation . Paul Scofield’s haunting narration is masterful. Scofield, known for A Man for All Seasons, adds that extra weight and gravitas, making the city feel like both a character and a mystery. Forget the book and organise a screening at your local independent cinema and invite us all. BFI have a good interview with him for more detail on why he chose to use a static camera .