What happened to Glasgow's visionaries?

On the Bruce Report and the future of Glasgow City Centre

When I first moved to Glasgow I lived in a flat overlooking the M8 motorway. I’d been reading a lot of JG Ballard and it felt vaguely exotic. I didn’t think about the pollution, the inhuman scale, or the relentless hum of passing vehicles; Glasgow was a strange, new place that I wanted to embrace on its own terms.

Douglas Adams’ quote about technology applies equally well to architecture:

Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works. […] Anything invented after you're thirty-five is against the natural order of things.

When you move to a city you accept the way it is—some bits are nice, some bits are ugly—you accommodate yourself as best you can. Only after you’ve lived there a few years do you stop and think about why it is like it is.

Glasgow is one of the great Victorian cities. It built its wealth through the transatlantic tobacco trade, then flourished as the world's centre for shipbuilding. Workers flocked from the Highlands and Ireland, keeping labour costs low, allowing the merchants to build beautiful infrastructure such as the city chambers, various winter gardens, the necropolis, lots of sturdy tenements, and the most extensive tram network in Europe.

By the end of the World War II, Glasgow was in transition. It was still a vital industrial hub, but some of the tenements were overpopulated slums and the air quality was bad because of the factories. The grand Victorian buildings were covered in soot and felt fusty compared to the skyscrapers being built in the United States. Something had to be done and one of the proposals was The Bruce Report.

Lots of people talk about the Bruce Report1 and how it transformed Glasgow, but few make the effort of visiting to the Mitchell Library to read it. What you find is a visionary document advocating levelling the city and rebuilding it along ‘rationalist’ lines.

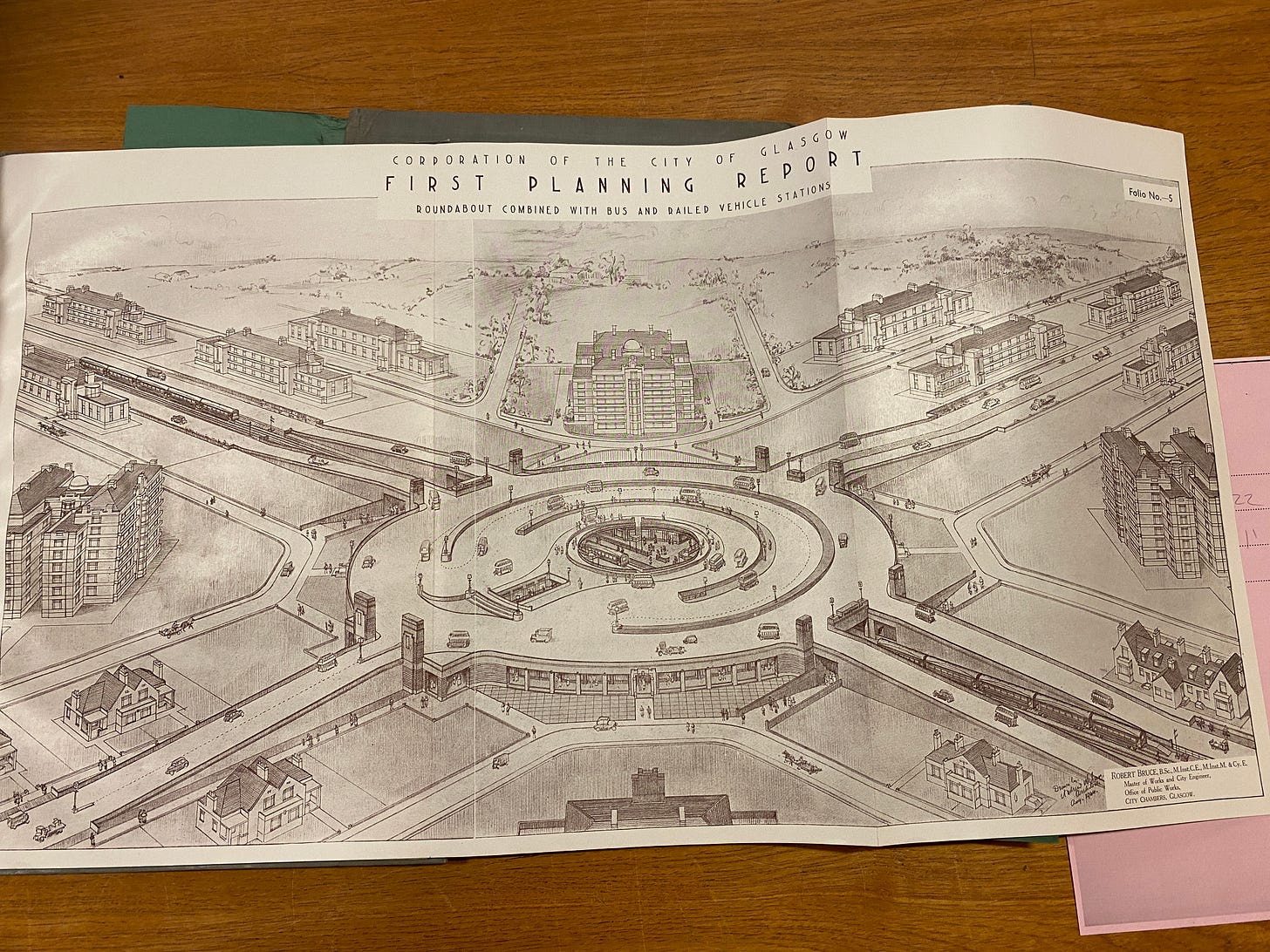

In Bruce’s plan, the inner city would be surrounded by a ring road with multiple transport hubs. Huge flat blocks would be built surrounding an entirely new civic centre.

It was supposed to be glamorous and modern, but to really see how bleak it would have been, check out this 3D visualisation produced for BBC Four’s Dreaming the Impossible: Unbuilt Britain.

In the preface, The Lord Provost wrote ‘The day of haphazard development is past, and the value of careful planning is being more and more appreciated as schemes,2 long thought of as mere fantasies, are brought to fruition.’

It’s difficult to grasp how much faith people had in the ability of planners to solve what would come to be known as wicked problems. The efforts of activists like Jane Jacobs to prevent engineers like Robert Moses from destroying the fragile ecosystems that had evolved over many years now seem heroic. Alas, in Glasgow, the planners won and tore up entire neighbourhoods.

The Bruce Report is obsessed with efficiency. In this illustration, a roundabout is combined with a bus and railway station to make it easy to make your next connection. You’ll notice that the roads populated by lots of buses, a couple of vans, and the occasional car.

What the planners didn’t anticipate is that the motor car would come to dominate. Cars, cars, and more cars rolling along a motorway that splits the city in two.

The car was the spur to modernity, but it is a symbol of freedom which destroys the freedom of others. Space, freedom, liberty: these are the emotional tones in Oscar Marzaroli's promotional film Glasgow 1980 (1971).

The glamour of the empty freeway, the huge Kingston Bridge towering over the city, it is all quite seductive ... if you're in the car. Not quite so much if you’re breathing the air, crossing the road, or being sent to live in a leaky high rise away from your friends.

Glasgow now has some of the worst air pollution in Western Europe and there are several primary schools within 100 metres of the M8. It is surely criminal that these children are breathing in toxic fumes everyday.

The elites in society were the first people to get cars and became addicted to the freedom and speed it gave them. Cars allowed them to live wherever they liked and commute into town, rather than live amongst the rest of society. Clive Thompson wrote an interesting piece recently about how infringments like ‘jaywalking’ had to be invented to criminalise normal behaviour. Previously, people could walk in the street without fearing for their lives, safe with the speed of trams and horses.

Despite all these caveats, I admire the modernist dream that the world can be rebuilt from scratch. It’s good to be ambitious and try to solve long-term problems. Just because things didn’t quite work out, doesn’t mean we should give up. We can learn from experience and plan better, rather than living with the Cheems Mindset, which believes nothing is possible.

Visiting New Glasgow Society’s hustings event a couple of weeks I was struck by the lack of ambition and was inspired to create the meme at the top of the page. The politicians sounded powerless: constrained by budgets, overawed by history, and incapable of seeing new ways to improve things. Most of the conversation was about saving derelict buildings (which, I agree, is important) and preventing the more egregious flat developments, but there was no sense of vision.

Imagine for a second there were no budget constraints and you had unlimited resources to redevelop your city. What would your priorities be? What is your vision?

Most people I know would ask for things like cycle lanes, leisure centres, a skatepark, or some such. They might fix up a few old buildings to make them a bit more eco-friendly, but at no point would they say something like the Bruce Report.

Where are the visionaries?

One visionary is the ReplacetheM8 account on Twitter, which shows the economic, social, and environmental benefits of removing supposedly ‘essential’ motorways from city centres.

Another visionary is my friend, Ellie Harrison, who after spending a year writing a book on The Glasgow Effect, came to the conclusion that shutting the M8 would improve health and reduce carbon dioxide.

Removing the motorway from the city isn’t a retrograde step where we give up on modernity. It is a positive, human-scale vision that values community and health. The M8 is literally falling apart as the ageing concrete cracks and we are spending millions repairing it. Let’s get rid of it and build something that allows people to breathe.

Published March 1945 and officially known as the First Planning Report of the Glasgow Corporation by Robert Bruce, Master of Works and City Engineer.

The word ‘schemes’ has stuck around in Glasgow, denoting the concrete housing estates that have blighted the lives of many.

Really enjoyed reading this …. Glasgow is a fantastic city …. motorway free would be wonderful.

Nice piece Neil!

Grand visions look nice on paper, but personally I love cities that have grown up in an

higgledy-piggledy way and the excitement of walking a city not knowing what is around the corner as you shift between architectural styles. Particularly love places that have kept parts of their medieval footprint and have grown organically!