Wat do you think wehn writers mispel words: or misuse punctuation; or— just thinking outside the box here—can't get through a sentence without resorting to cliché?

Perhaps you'll forgive them the first couple of times but it doesn't take much for one's confidence in someone to be undermined. It's like a grimy fork in a restaurant or a wonky seam in a jacket: the bubble of trust is pricked. Consistency is the difference between the amateur and the professional. The latter has smoothed away all that is jarring from their work. Or, if it is jarring, it is jarring intentionally.

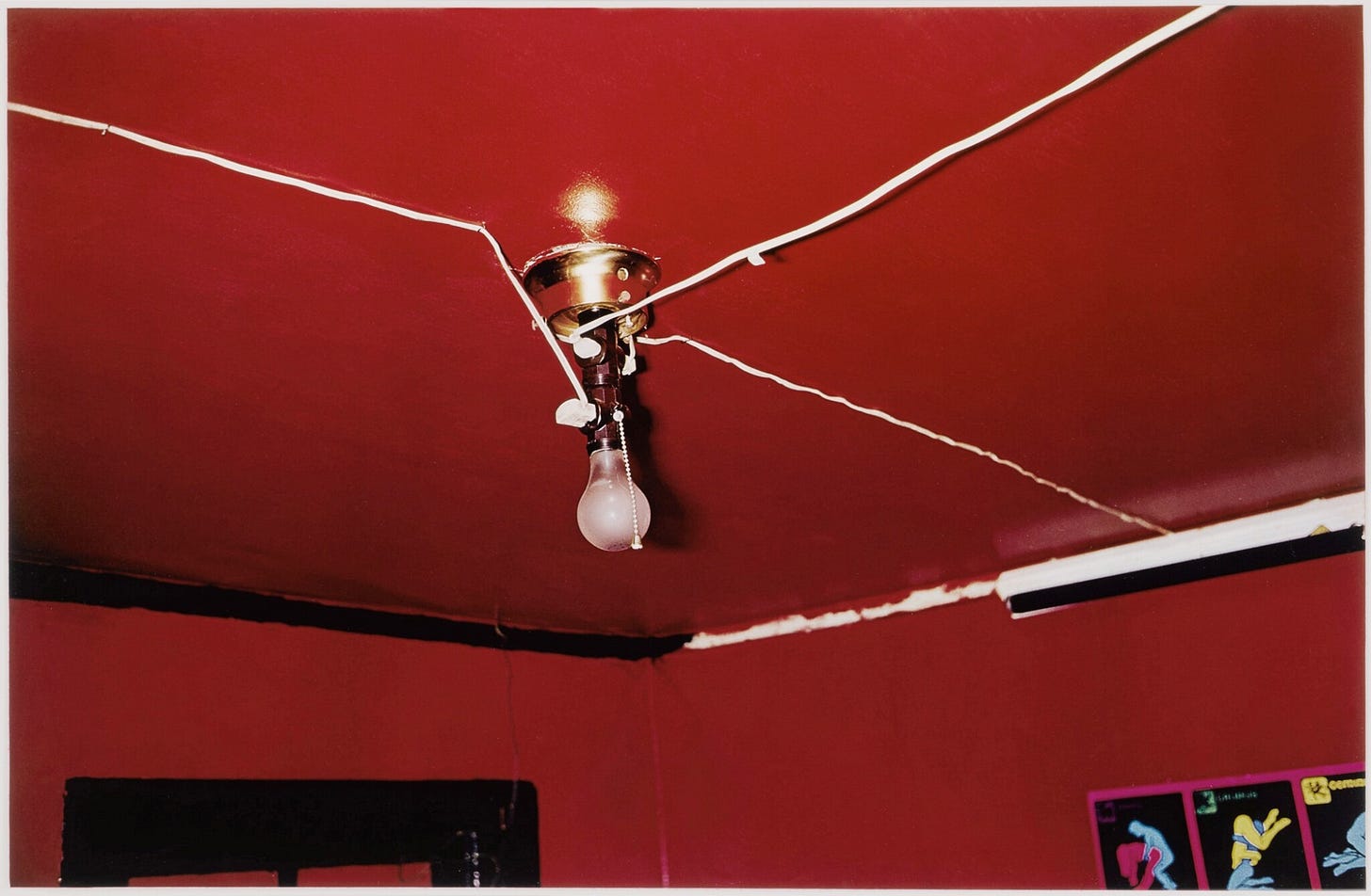

This week I have been immersed in the work of William Eggleston. What is amazing about his photographs is that, even if you don’t care for what is depicted, there is nothing false or wrong in them. Experiencing them as a collection is hypnotic, they are so unerringly well-composed. Such consistency inspires faith, faith that they are worth paying attention to.

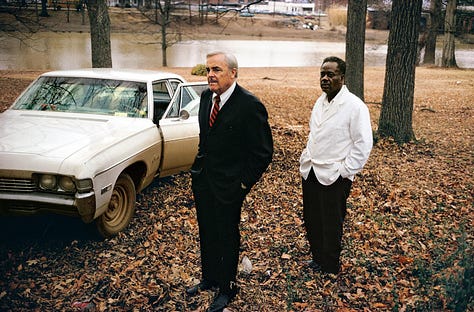

Eggleston’s most recognisable photographs are his mundane scenes of the Deep South. He avoids obvious subject matter, urging the viewer to look afresh. The images evoke peak Americana, a world of diners and gas stations and long summer drives in big cars. His aesthetic has been consciously imitated in films like David Lynch's Blue Velvet, Sophia Coppola's The Virgin Suicides, and Gus van Sant's Elephant. His photographs have been used on albums by Big Star, Primal Scream and Jimmy Eat World. However, as Sean O'Hagan writes, his influence is "so pervasive that it goes unnoticed. In fashion shoots and films, advertising and art photography, Eggleston's everyday view of things, initially dismissed by critics in the mid-Seventies, is now the prevalent aesthetic."1

Eggleston achieved notoriety in the mid-70s for his use of colour. Incredibly, his solo 1976 show at MoMA, curated by John Szarkowski, was the first exhibition there to feature colour photographs. It was the fine art photography equivalent of Dorothy stepping into Oz. The medium was never the same again,2 though he faced resistance. Henri Cartier-Bresson told Eggleston, “colour is bullshit."

By bullshit, I assume Cartier-Bresson meant that colour is deceptive. But the saturated colours produced by the Dye Transfer process feel true to me. They are rich, vivid, and never slip into gross hyperrealism.

Eggleston’s consistent colour palette allows the viewer to feel like they’re in a self-contained universe. Indeed, he described his photographic work being “parts of a novel I’m doing.” Can you see the detective story unfold below?

The photographers I’ve been looking at in this series worked almost exclusively in black and white. Partly for technical reasons, but mainly because colour was seen as a distraction from the formal composition. When colours in photographs don’t conform to expectations they are jarring. The fact that Eggleston is never jarring is testament to his artistic vision.3

The photographs in this article are used for criticism and review under the Fair Dealing provision of UK Copyright Law. All rights to the image remain with the photographer/copyright holder. This use does not claim any rights to the original work and is not for commercial purposes.

The New York Times critic, Hilton Kramer, wrote: “Mr. Szarkowski throws all caution to the winds and speaks of Mr. Eggleston's pictures as “perfect.” Perfect? Perfectly banal, perhaps. Perfectly boring, certainly. […] The use of color, alleged to lend a special distinction to these pictures is, to my eye at least, similarly commonplace.”

Recently, however, work has been done to rediscover artists who were working in colour before Eggleston.

I love that Eggleston stopped using the viewfinder, trusting his knowledge of the camera to know what he was looking at. I also love that he only takes one photograph of each scene. It either works or it doesn’t.

Eggleston has such a talent for photographing the ordinary. His use of colour and atmosphere always amazes me. Thanks for reminding me to take down one if his books from my shelf.

I always found something affected me by the subtle darkness of many of his images. His sense of brooding, like the image with the gun, really makes them something special.