An Interview with photographer Simon Murphy

The road to Govanhill, paved with good intentions

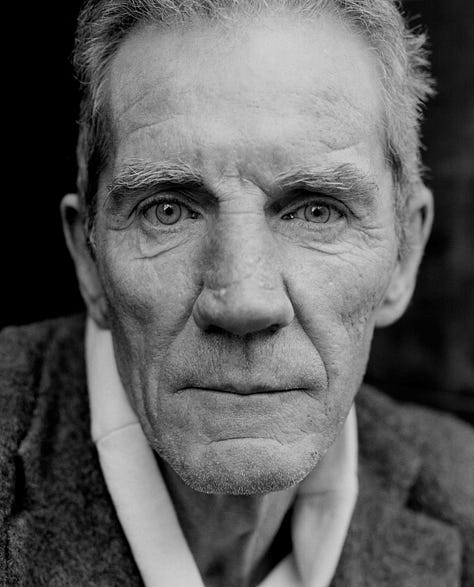

From the moment I first saw Simon Murphy’s portraits, I’ve been obsessed with the rapport he has with his subjects. They seem relaxed in his presence, true to themselves.

This is not easy. Turn a camera on most people and their face will tighten into a fake smile. They look at the photographer with suspicion, wondering what they want. Murphy consistently gets past such resistance and establishes a powerful connection with them.

This month sees the launch of Govanhill, Murphy’s first major exhibition and his first significant book, giving me the perfect excuse to ask him about his methods and what drives him as a photographer.

Neil Scott: For those unfamiliar with Govanhill, could you paint a picture of what it's like?

Simon Murphy: Govanhill is an area in the south side of Glasgow that’s about a mile squared. It's always had a bit of a bad reputation and has been the place where people first arrived in Glasgow as immigrants. The same planners who built New York built Govanhill. You think of New York and have this idea of people arriving in the new world. Govanhill is like that but on a much smaller sense. It has always been a melting pot of cultures and nationalities. People came to Govanhill because there was relatively cheap housing and then, once they’d established themselves, they’d move out to the suburbs.

What makes Govanhill so compelling for photography?

It changes quicker than other places. Ten years ago you couldn't buy a fancy coffee in Govanhill, you'd get Nescafé in a polystyrene cup. Now you’re paying, I don't know, four pounds for a coffee1 … I don't buy coffee there anymore. For a photographer, change is brilliant. That feeling of nostalgia triggers something in people, even if it's recent history.

Your own background, as a photographer, was working for newspapers and magazines. Did you ever go into the project with a newspaper editor’s eye?

No. A newspaper might have a political slant to it, but I see it as a project about humanity, not politics. But the way I photograph is definitely influenced by my newspaper background. I used to shoot fashion for the Herald Magazine and with fashion there's a lot of direction and a bit of flattery involved. When you meet a celebrity, you've got to click with them instantly. Same with this project. I want them to look as good as they can. I get people to raise their chins, turn their heads to the side, or stand in a certain way where I think they look cool.

The other reason is that I don't want to be chased out. The project has to connect with the participants. When you photograph people in what others would consider deprived areas, you get this accusation of poverty porn. But today someone had the opposite accusation and said: “you photograph people like they're in a Sunday supplement fashion shoot.” But, yeah, I do photograph people in that way.

Could you tell me about how you make these amazing connections with people?

You've got to do work on yourself. You've got to ask yourself: why does this matter to me? Why does this place matter to me? What does it say about me? If your intentions are pure then it is easier to approach people because you can be honest. When I see someone that I respond to, I immediately tell them what it is that moves me about them — whether that's because they look cool or they've got a cool coat — even if they're rough or a bit edgy. People see the camera, they study me, and within seconds they've made their minds up about whether they’re going to do it or not.

Are there any examples where you felt like you've crossed a line with people? Have you looked back at a photograph and thought “I shouldn't have taken that” or “I'm doing this for the wrong reasons”?

There was a photograph I made recently where there was a woman with her legs around the lamppost and she looked a bit out of it. I would never normally take a photograph like that because I like to communicate with my subjects. Even subjects is not a good word … I like to have a dialogue. But I had the camera, I was doing street photography and I was trying a new project and I wondered “is this a shot?” and I brought the camera to my eye and I pressed the button. Immediately I knew that was the wrong decision. That picture will never see the light of day.

I used to think that if a photograph was beautiful enough it could justify any ethical issues. I don't think so anymore, but I like the Vivian Maier thing of never developing anything and then fifty years later they can be published without harming anyone. Maybe the same could happen with this photo of the woman around the lamppost.

Yeah, you've got to allow time to pass. In time, a photograph can become more than that person, that relationship. And the viewer brings something to it too. I can't control what the viewer brings to it but that's part of the equation as well. It can take on a life of its own and sometimes the person no longer represents that person. They become bigger than that. Do you know the photograph of Oscar Marzaroli of the boys in high heels in the Gorbals? That’s not about those little boys now, it’s about people's childhood. It was tough in Glasgow, but people found joy in those circumstances.

No one objected to Raymond Depardon’s photos of Glasgow because they were from forty-odd years ago. If they were taken today they would be ripped apart as exploitative. But I think it’s good you’re exhibiting these photos now because it’s going to be amazing to see 200 people from Govanhill descending on the gallery for the opening. Are you looking forward to having everyone in one place?

I'm nervous because some people might not like the photographs. Most of them I've had dialogue with and we've got good relationships, but there's one with a young school girl and she's got a cigarette in her hand. I've never put it on Instagram because I had her name and I usually title my photographs with the person's name, but I lost it. I'm worried that her mum and dad might not know that she smokes and it might get her into trouble. So I’m nervous about that.

But this is from a few years ago, right? Maybe she's old enough to smoke now?

She’ll be 17 now, but she wasn't then. I needed time to pass for that one.

People will love being in a big exhibition. It was wonderful to see the ex-homeless people at Margaret Mitchell’s show, proud to be part of something so beautiful.

That's the thing, that pride. When the criticism comes, which it will, that sense of pride is what will matter most. I remember when I had the window exhibition in Govanhill and there was one comment on the Street Level website that accused me of exploitation. It's the one thing that stuck with me, out of all the positivity. It just played on my mind. But in a sense, it's good because it makes you confront those accusations and solidify your reasons for doing things.

What do you think about photographers who do the opposite? There's a guy, Dougie Wallace, who they call Glasweegee. He goes around Knightsbridge and Soho and takes photos without permission. Often quite antagonistic. What do you think of those kind of photographers?

With any sort of artist, there's an urgency, a need to create, to do. You have to do the work you're compelled to do. You have to face the criticism. You can't let the critics tear it down. It’s a problem in art schools just now where everything is critiqued so much, there’s so much fear, that a lot of the projects are just about that person and their mental health. That's the project. They're scared to step out of that bubble.

For me, Dougie Wallace’s pictures make me look and they're memorable. He has to ask those questions of himself, but I think it's important that he's doing what he feels he needs to do. And, yes, you have to deal with the criticism. But you can't let that stop you from doing what you do. I have my ethics. I want to elevate people. I love Govanhill. It's rough, but I love it.

We live in an age where everyone has a smartphone and street photography is ubiquitous, which makes that ethical relationship problematic. With Martin Parr and Dougie Wallace, whatever you think of their ethics, you can't help but look at the photographs.

Martin Parr gets a lot of criticism but he has these photos of Tories in the 80s that no one else recorded. That's our only insight and thank goodness he did. If he didn't do that, we’d have to rely on our memories, which are twisted and tinted as well.

What I like about your photographs is that not only do they have a timeless quality, but they reveal something about now. People are recognisably from right now. With the Govanhill series, there is a lot of diversity, not just diversity of culture, but diversity of what it means to be a human. What have you learned about human nature through doing them?

I’ve learned that if you open yourself up and shake off the shackles of fear, great things can happen.

Do you have a sense that photography can reveal universal fears and longings?

I don't know. But we don't spend enough time looking into each other's eyes and trying to understand people. In Govanhill, you might see a group of men on the corner. Fear might kick in, sometimes for justifiable reasons, so you walk by with your head down and you hold on to that fear because your head's down. If you walk by the same group of men, look into their eyes, smile, say, “Alright, brother,” fist bump them, even if you don't know them, it changes, and your world becomes a bit bigger.

Have you ever encountered a truly bad human being?

I've been threatened to be stabbed. But the same people, the next week will be laughing and joking with me.

Was this before you asked for the photograph or after?

During! I'm not trying to paint Govanhill in any particular way. You've got groups that promote the place, like Govanhill Go and Greater Govanhill. I love Govanhill Go, but if you live in Govanhill you know that it's not always like that. Then you've got other people, who often don't live in the area, they go to the opposite extreme and paint it as a slum. What's the reality? None of those are the reality. All I do is my version of Govanhill, a place that I love, that I'm well aware is rough around the edges. I've had some pretty mad experiences in Govanhill, I've been in fights in Govanhill. But that doesn't make me dislike the place or the majority of people.

Is there anyone you wouldn't take a photo of?

For moral reasons?

Yeah, I guess. What are your criteria, apart from that they’re interesting?

That's number one. It's about visuals. That's what photography is. The person has to be visually striking in some way for me to want to photograph them. But we've got so many facets as people, I don’t think there's anyone I wouldn't photograph.

What I like about Greater Govanhill is that they call what they do “solutions-focused journalism”. They don’t want to make things any worse than they are. Do you think photography can be solutions-focused?

Yeah, but it's not my photography. It becomes PR and I'm not interested in that at all. It creates its own problems. It hides things and seems forced. For instance, the people who put together a college prospectus will be keen to show a range of ethnicities and they’ll select those people just to represent. If you want to do things justice you have to actually get rid of that mindset completely and put the time in. Eventually, if a place is diverse, if you spend enough time, it'll show. You've got to be in it for the long term.

I remember when I first started the project all I was getting was old men with cigarettes. But that's partly because I find it easier to speak to an old man outside a pub. Imagine I did a project called Govanhill that was all old men smoking cigarettes it wouldn't be representative. But at the same time, if I had said okay, I need to find a Roma person, a Polish person, an African person, it’d just be so forced.

You never have people smiling in your photographs.

Maybe because I'm miserable. But I think a smile is a mask. I've caught some real moments of joy, but it has to be very spontaneous and that's rare because I shoot with a medium format camera. It has to be set up and composed, it doesn’t have autofocus. If someone moves their head forward and smiles, I've got to re-compose or re-focus. It’s like Victorian photography. Why do we think the Victorians were such a stiff people? They weren't. But the photographs look that way because of the technology.

It is very hard to get the eyes to match up with the smile, right? That's how we know it's fake. I wonder if it’s also because you’ve got this Mod vibe. Do you think we still have tribal identities in the same way as we used to with Mods?

100 per cent. Yeah, it's like the goth girls in the skatepark. That’s a long-standing tribal identity.

Did you find your tribe in school?

I was a skateboarder at school. But in the nineties, I found Oasis and that was my life: the gigs and the attitude. This was before Lad culture and Nuts magazine. Before that, the Oasis mentality was “we're from a council scheme, but the world can be ours.” The other thing that differentiated Oasis from what came before was that the grunge scene was very down on life. Very head down, hair over the eyes. Oasis wasn't like that. I do believe that you gotta make it happen. What was the song?

Aye, that was it, that was the first song on their album. It’s so different to the culture now. People are very insecure, even people with strong identities, inside they are crumbling. But if I don’t get up and go out and photograph, what am I going to have? Nothing.

Is the Govanhill project finished now?

I'll carry on but I've taken a break from it because the exhibition and the book have taken up so much of my time. It broke my rhythm. I used to be religious and be out all the time. But I think it would be nice just to leave it for a bit … I'm not sure it's a great time either for Govanhill.

Is it too cool? You've made it too cool.

Aye, that's my fault.

What’s the next project?

No other place in the world means as much to me as Govanhill. I can't do a project in East Kilbride or Springburn because I just don't have the connection there. But what I do have a connection to is Glasgow, so I think the next project will be wider.

And now that you have the exhibition and the book, what’s next in terms of ambitions?

It's difficult to say because the Street Level show was always the dream. First and foremost, though, I'm a teacher. That's how I see myself. Everything's connected with my teaching. That's my goal: to be a good teacher and to inspire my students.

Also, you can't go to Govanhill now because you know too many people. You’re a celebrity there. I'm not a fan of paparazzi but my wife loves the actor Iain Glen and I took a sneaky photo of him cycling in his flip-flops. I felt a bit dirty but I kind of admire the bravery of the paparazzi.

It's what they do. It's not what I would do.

Did you know any paparazzi when you were working for newspapers?

No, my job at the Herald Magazine was totally unique in that I would go out and photograph artists who were there to promote something. There was a mutual need to get something good out of it. But I once got asked by the editor to take a picture of an ambulance. They just wanted a stock picture of an ambulance going fast. I refused to do it and got disciplined. I just didn't feel comfortable doing it. Someone might be in that ambulance.

How long ago was that?

15 years ago.

What would you say to the Simon Murphy of 15 years ago?

I would tell him to make more use of the time I had back then. I was too chilled. I should have been in Govanhill taking these photographs. I've got much more drive now.

Maybe you need those lost moments to have a sense of urgency. Photography is inherently a nostalgic medium.

It is. The minute you take a shot, it’s history, it's gone. Photography is about capturing that moment.

Simon Murphy’s exhibition Govanhill opens at Street Level Photoworks on 21 October 2023. The first edition of his book, Govanhill, has sold out. Hopefully, a second edition will be published soon.

Bonus! Five Photographers Who Inspired Simon Murphy

Simon Murphy: It changes all the time but I'm going to say …

1. Christine Stevenson

A friend of mine who was my first photography lecturer at North Glasgow College. No, you won't know any of her work because she was my college lecturer. She opened my eyes with pictures by people like Henri Cartier Bresson and that lit a flame in me. She's the most inspiring person in my life.

2. Matthew Sowerby

He was the lecturer when I went to do an HND at the College. Now there were other lecturers there, but he was the one that would come up and show me pictures. At the same time he was teaching, he was being a photographer and he was photographing bands like Travis and people like Ewan McGregor. I thought "that's amazing, you can do that as well."

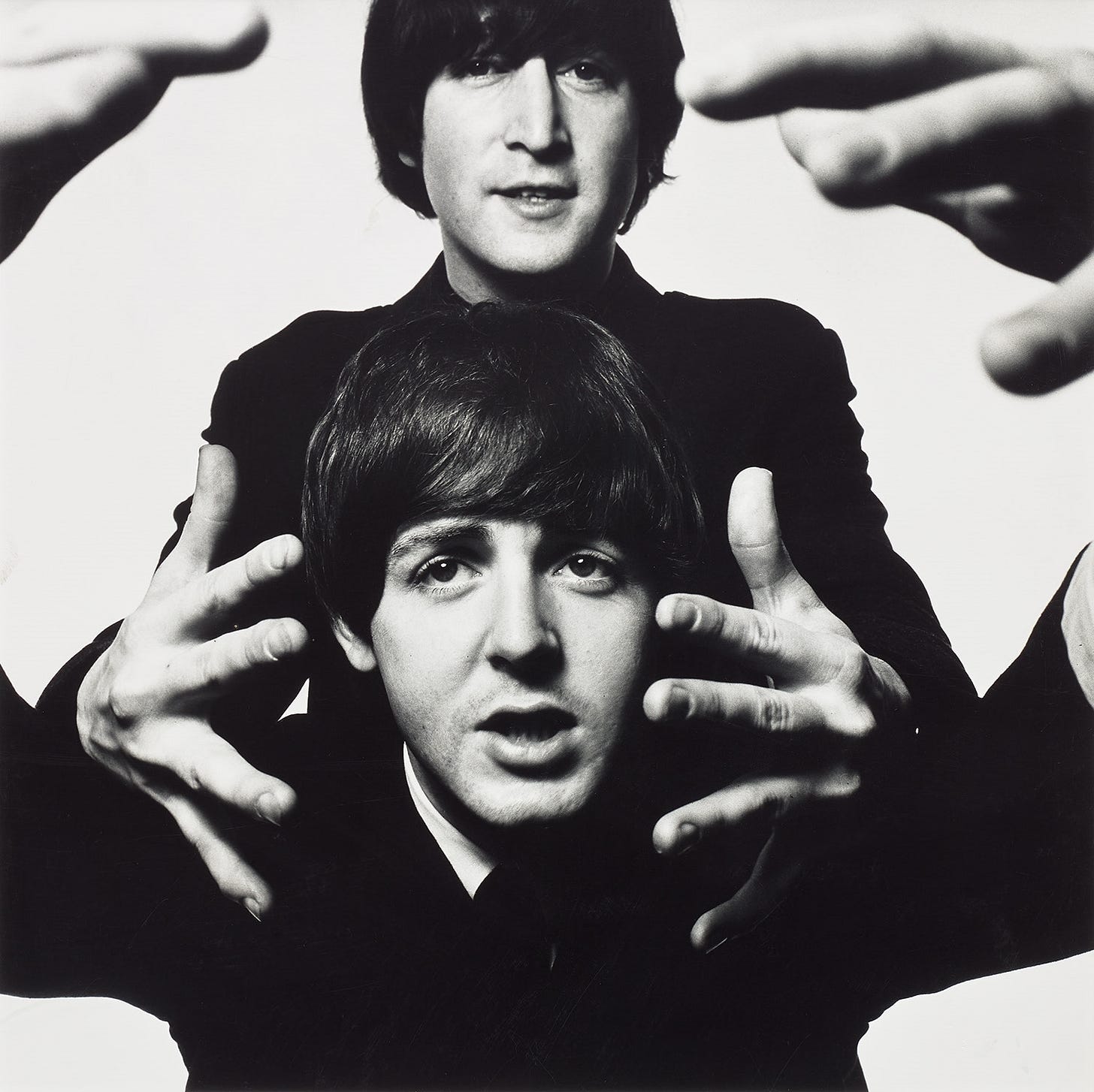

3. David Bailey

I wasn't very musical, but I'd love to be a musician. I saw these pictures of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, and David Bailey was pals with all of them. Photography was this way of being in that company and being part of that group, but bringing something else to it. I thought, “what a life!”

4. Sebastiao Salgado

Salgado was inspiring in a different way because there's no celebrity there but it was opening my eyes to the world. Seeing his work for the first time in all the countries he's been to it was just ... "wow". The print quality was beautiful, but also the thought that that could be your life, you could go to these places.

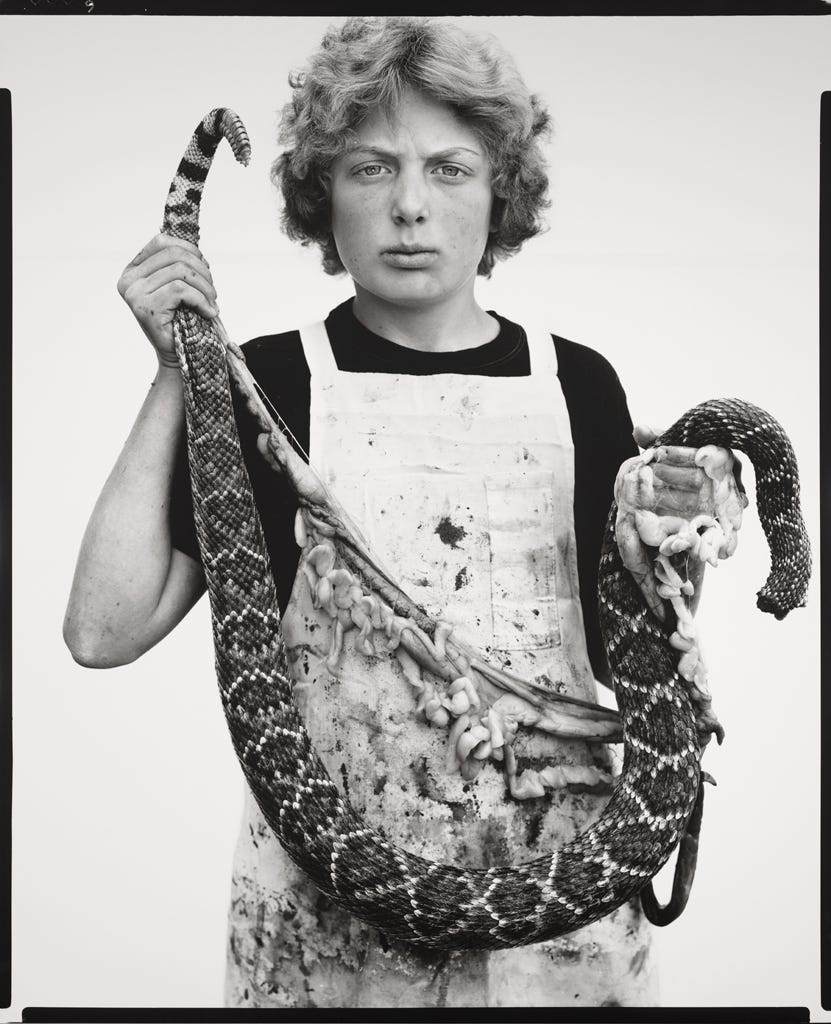

5. Richard Avedon

I suppose he's closer to David Bailey in the sense that he was a superstar photographer with a flamboyant lifestyle. But it was his work in the American West that resonated with me. These beautifully detailed images of people in the Midwest of America doing a rattlesnake cull. I didn't recognise these people, but in these people I recognised something of myself, something about humanity. These pictures were stronger than the flash rock star looking to the side or looking up. These pictures were direct.

Govanhill Go dispute the £4 coffee.

‘A smile is a mask…’

Really enjoyed this, particularly the perspective of letting enough time pass for the context to change.