Brutalist Glasgow

A brutalist photowalk plus an interview with Rachel Loughran the curator of Brutal Glasgow

Developing an interest in architecture is one of the most rewarding things you can do. Every walk in every town becomes a trip to a living museum. Art, engineering, history, fashion, technology—they are all there for the attentive flaneur.

Glasgow has hundreds of architectural gems from its Victorian heyday, with accounts like This is My Glasgow scouring the city for beautiful buildings and interesting stories. Such stories are usually celebratory but not always. Rarely does a day go by without Niall Murphy, director of Glasgow City Heritage Trust (GCHT), lamenting a fresh growth of buddleia.

With brutalism—broadly defined as the monumental concrete structures erected between 1955 and 1980—opinions are mixed. Architects, urbanists and psychogeographers love brutalism. You’ll often see them with cameras, capturing its bleak intensity in black and white. For them, brutalism conveys the alienation of modern life. They adore the bold, sculptural forms, the clean lines and pure geometric shapes … before returning to their stately Victorian homes.

For people forced to live or work there, brutalist architecture was often a brutal experience. Damp, cold concrete led to anti-social behaviour and addiction. It was a rationalist dream that turned into a nightmare. All over the country, brutalist buildings are being torn down.

But maybe this is a mistake. As

writes in Darkrooms Magazine:1Buildings are most in danger of demolition a generation after they were built. Some deserve to be. But too often the default is to knock everything down without appreciating that some should be kept.

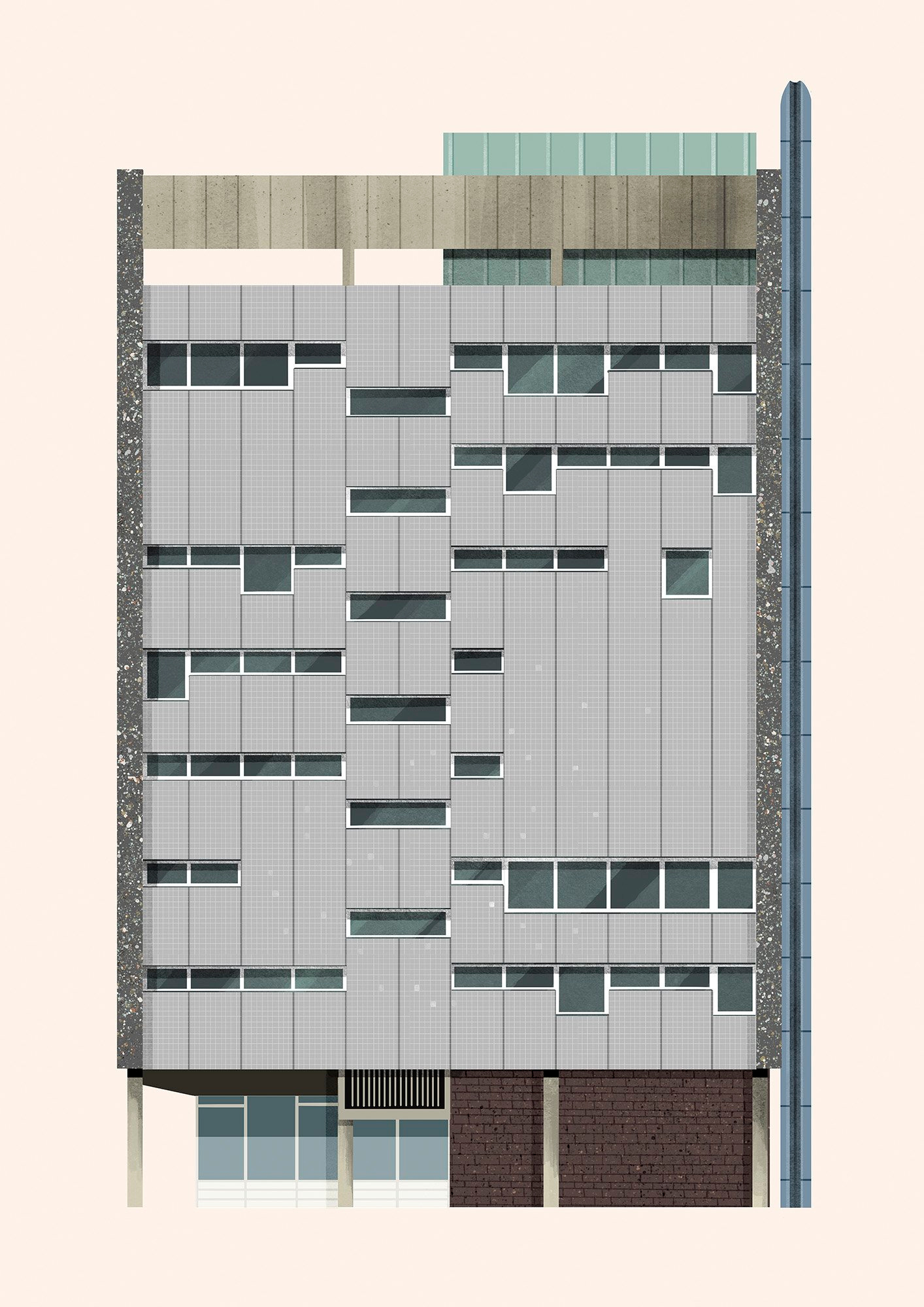

The current exhibition at GCHT attempts to reckon with the legacy of post-war architecture at a time when it is under threat. Curated by Rachel Loughran, Brutal Glasgow is based around Natalie Tweedie’s stylised illustrations of modernist buildings as a way of investigating the city’s social and architectural history.

If you can’t make it to Glasgow to see the prints in person, do check out the website. There are texts by writers like Owen Hatherley and Johnny Rodger which grapple with the legacy of brutalism. It is not quite a celebration but a nuanced attempt to place it in context.

The exhibition might also inspire you to go and investigate for yourself. That’s what it did for me. And so, what started as a quick lunchtime stroll turned into a three-hour circuit of the city as I tried to get a practical understanding of brutalist architecture.

A Brutalist Tour of Glasgow

In his influential essay, The New Brutalism (1955), Reyner Banham identifies three qualities that define the brutalist buildings:

Memorability as an Image

Clear exhibition of Structure

Valuation of Materials ‘as found’

By this definition, Glasgow Sheriff Court is strictly not a brutalist building. But it is monumental and unapologetic. Indeed, when listed in 2013, it was described as a “significant example of late-Brutalist architecture”. It certainly creates a feeling of rude solidity in the minds of those who come to stand trial at what is notoriously the busiest court in Europe.

Further along is the Clydeside Amphitheatre, an attempt to create a performance space on the river. Hidden from the road, it has become a place for youth to hang out and smoke hash. In the background is the pyramid of St Enoch Centre, whose glass represents a rejection of concrete.

A concrete sculpture of the Spanish Civil War fighter, Dolores Ibarruri, stands with her arms aloft. Described by one councillor as a “notorious Communist war criminal”, she represents the socialist dream of brutalism.

The first building I saw that appears in the exhibition, the BOAC, is defined by its copper shell and octagonal windows. When I asked which brutalist building they would save, surprisingly most Glaswegians picked this one. But it is easy to ignore, being overshadowed by the more ornate buildings on Buchanan Street.

Glasgow’s largest brutalist project is the Anderston Centre. Designed by Richard Seifert in 1972, it is located near the M8 motorway and was thus too far away from the city centre. The only people who go there now are psychogeographers with too much time on their hands.

I hadn’t intended to cross the motorway but saw the Pyramid at Anderston in the distance. Thankfully, the Bridge to Somewhere (formerly the Bridge to Nowhere) was completed in 2013, allowing pedestrians to cross from Anderston to the West End.

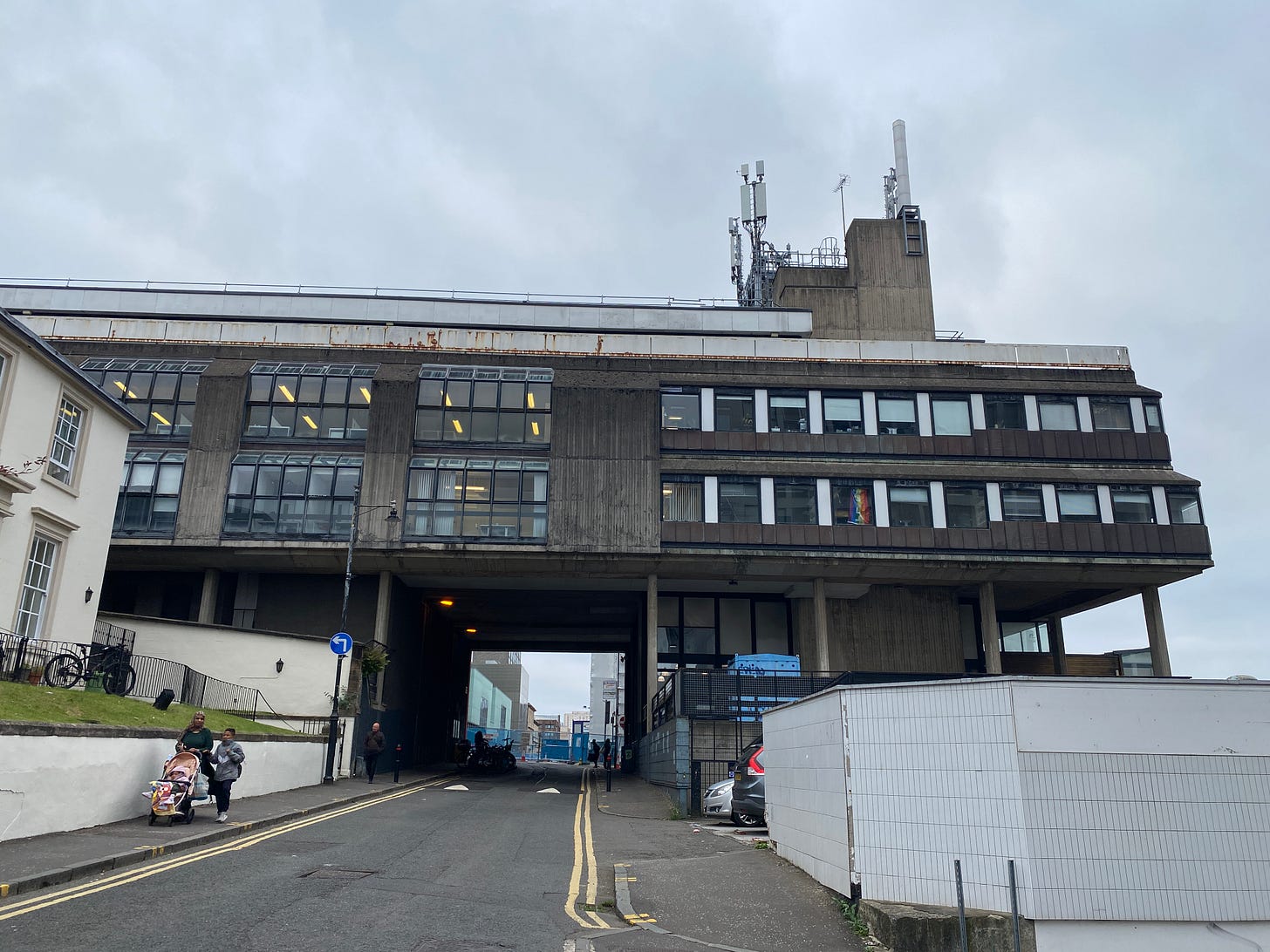

The real brutalism in Glasgow is, of course, the motorway running through the middle of the city. It is huge. It is relentless. And it is falling apart.

Of all the brutalist buildings in Glasgow, the Pyramid at Anderston is the most sculptural. Its forms are pure and harmonious, despite some decay.

The University of Glasgow has been covering up or getting rid of its 60s follies. However, the Rankine Building, with its ugly sculpture by Lucy Baird, remains in place.

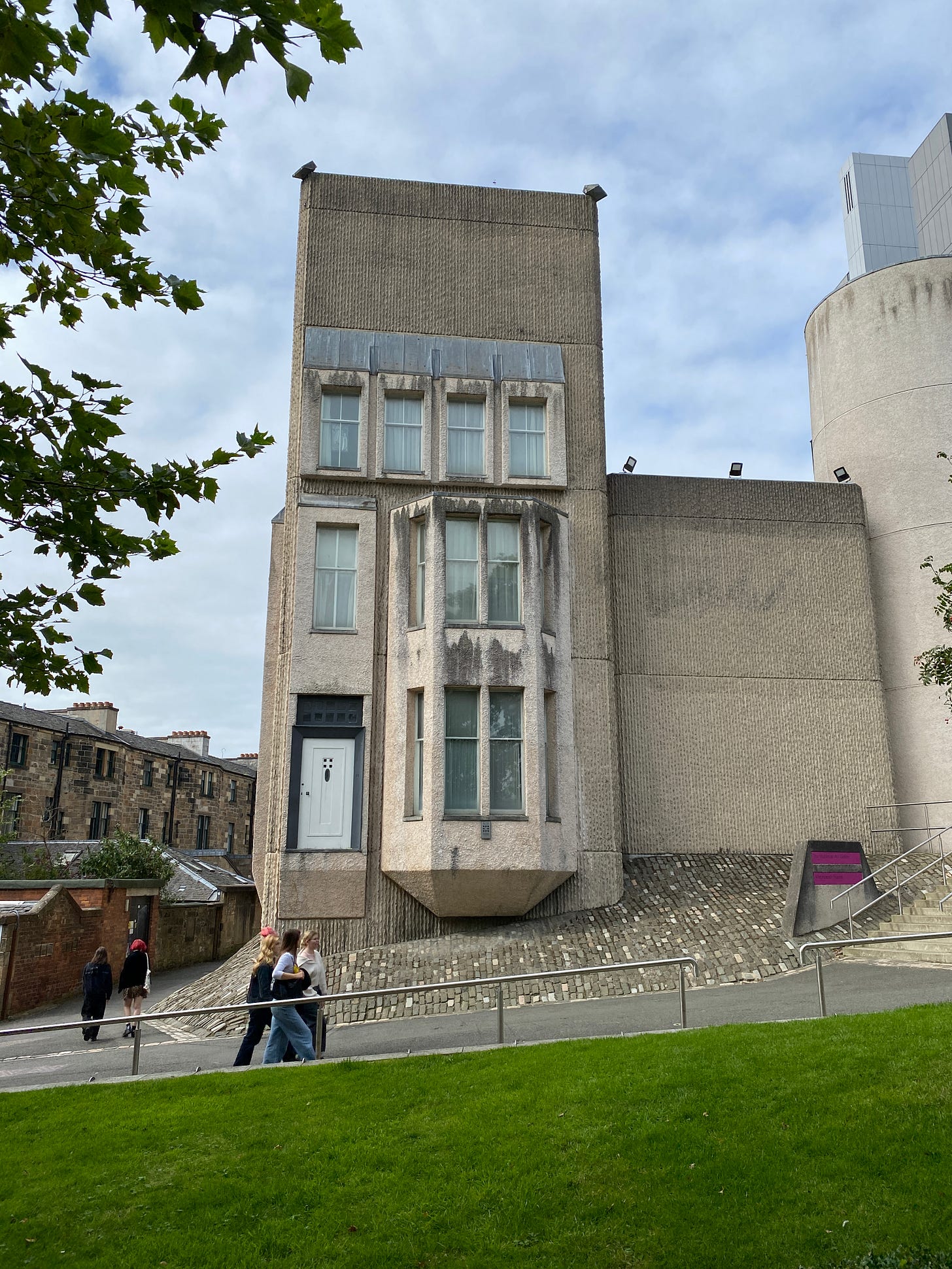

One of the University’s most successful brutalist buildings is the Mackintosh House, a meticulous recreation of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s interior design. The exterior is a bold brutalist reinterpretation. The concrete clearly shows how it was cast.

The last time I visited the stairwell of Queen Margaret Union, I found a syringe and a can of Irn-Bru on the steps. It seems that even in the leafy West End, the curse of brutalist alienation cannot be avoided.

The exterior of Hillhead Library is pretty uninspiring, whereas the interior is light, airy and welcoming. It is rare to see the inside of brutalist housing schemes and office blocks, but libraries provide a great opportunity to do so.

After walking back under the motorway, I reached the St Andrews First Aid building. With its huge red cross on one side and oddly pareidolic face on the other, it is certainly memorable albeit sinister. As with so many of these buildings, it is preferable to view the idealised Nebo Peklo version.

The Savoy Centre is tricky to take in at a glance, so we tend to focus on the details, such as the typography and Charles Anderson’s sculptures.

The enclosed bridge to the Savoy centre has been abandoned and is becoming overgrown with buddleia.

The Bourdon Building at Glasgow School of Art is famous as the place where architecture students learn what not to design.

The Met Tower, with its Corbusierian sculptures, was supposed to be transformed by the council into a tech hub. These plans have been abandoned. The building is better known as the “People Make Glasgow” building. Rory Olcayto calls out this slogan:

With Glasgow’s built heritage forever under threat of demolition, what message is really being shared here? ‘Don’t worry about the buildings falling apart around you or going on fire or the ones being boarded up, don’t worry – architecture doesn’t matter really - because People Make Glasgow.’

One of the trickiest things for Natalie Tweedie was to capture large buildings without cropping them. She told me that the old architecture department at the University of Strathclyde was one she had wanted to draw, but which had ended up being too wide.

The nearby Wolfson Centre would work quite well though.

Instead, she chose the monumental Livingston Tower.

My final stop was Our Lady and St Francis’s Secondary School, a category-A-listed building next to Glasgow Green. This is a good place to end—it is harmonious and aesthetically engaging. As the Barbican in London shows, there is no reason that brutalism can’t work. It just takes imagination and investment.

If you’d like to find these buildings, I’ve made a map of my walk with the locations marked.

Interview with Rachel Loughran

Neil Scott: I first got interested in brutalism through photography. There was a blog called Fuck Yeah, Brutalism which had these incredible pictures of sculptural buildings.

Rachel Loughran: Yes, there's a strong correlation between brutalism's appeal and how it's captured in photographs. Many brutalist buildings actually look better in pictures than in person. Just as Natalie [Tweedie] is experimenting with ideas inspired by 1960s textile art, using colour and depth of field to transform something perceived as ugly into something beautiful.

How did you come to be interested in brutalism?

It really comes from an interest in Glasgow: its built environment and how it is described in literature. There is a great period of literature coming from Glasgow in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. We have writers like James Kelman, Alasdair Gray, Liz Lochead, and Tom Leonard talking about the experience of place. Glasgow's identity seems so tied to the architecture of the city. The exhibition is about how people move in space. How do they interact with the city around them and how does the architecture they come into contact with affect their everyday lives: what they can do, how they feel, and where they go.

Do you have any book recommendations from that era?

A great book where you can read about Glasgow and its urban architecture is James Kelman's How Late It Was, How Late, which won the Booker Prize in 1994. We have Sammy, the central character, who wakes up and finds out that he's been blinded during his time in custody. He has to make his way around the city and experience it sonically and through touch. It gives you a strange sense of the city. You're trying to work out exactly where he is at a moment in time when he's feeling incredibly disorientated. I think that's a great novel about Glasgow's landscape without actually talking about the landscape as such. Then, of course, there's Lanark, which is the greatest 20th-century Scottish novel about the city and about how our experience of it affects us.

Architecture is full of embedded values. In Glasgow, there's an extraordinary contrast between Victorian and modernist values. Brutalism is often seen as a failed utopia. Do you think this makes us less optimistic about the future?

It's become commonplace to think of brutalism as a failed utopia, but, in Glasgow, I don't think it was ever seen as utopian. At the time of brutalism, there was horrific overcrowding and unsanitary conditions for many people. It was building in an emergency situation rather than building a utopia. People desperately needed homes and we needed to give them these homes as fast and as efficiently as possible. If we go back to the Smithsons’ loftier ideas about streets in the skies, there’s a sense of the fanciful in it. Whereas, in Glasgow, that wasn't really what was going on at all.

I get that, but having read the Bruce Report, and seen the images of what they wanted to create, it feels pretty utopian. The city planners went to America and were seduced by these big highways and multistorey car parks. What was your selection process … I am curious about why you didn’t include things like The Pyramid at Anderston?

There was a lot of pragmatic decision-making going on there. Natalie had produced 12 images of brutalist buildings and I wanted buildings that represented different areas of Glasgow. The next stage was thinking about what stories could come out of these buildings. So it's a blend of pragmatism and storytelling.

Have you had any extreme reactions to the show?

There have been a few comments along the lines of: "There shouldn't be an exhibition on brutalism—these buildings are just ugly." But the story is much more complex than that. In the exhibition, we try to create an ecosystem behind the images to soften the love-hate, right-wrong polar opposites that are very divisive. It doesn't necessarily need to be like that.

No, it doesn't. However, two of the buildings have already been demolished with more under threat. Do you think this exhibition might help to save some brutalist buildings? It is, after all, being shown at the Glasgow City Heritage Trust.

No, that would be a very lofty ambition. My central aim for the show is for folk to look at their built environment in a renewed way. I don't expect people to retain every ounce of information. They might also just look at the buildings they are interested in and that's fine. But the aim is not to evangelise or contribute towards a campaign. It's for people to enjoy and experience and think about their landscape differently.

For people like Paul Sweeney and Niall Murphy, who are passionate about Glasgow, it has been difficult to stay positive when buildings are falling apart.

Glasgow has a lot of architectural and planning issues. This show doesn't tackle that head-on. If it's in the back of people's minds after they see it, cool. But you probably have that in the back of your mind anyway. It's an exhibition, and it is in the wild now, so they should do with it as they feel.

Thank you, Rachel.

Brutal Glasgow is open until 27 October 2024.

Coincidentally, Issue 5 of

’s Darkrooms Magazine was published this week. Very pleased to say that it features my photographs from Riga.

Very interesting post about some of my favourite things! I wish I was closer to Glasgow as I’d love to visit the exhibition and then follow in your footsteps.

Excellent article 👏

Corby town centre is /was a complete example of brutalist architecture… a depressing place.