Edward Weston

On vitality ... by way of Geoff Dyer and D.H. Lawrence

This newsletter exists because of embarrassment. Last October, I went to a gallery where the books owned by the writer Leigh French were being shared after his death. I picked up a couple about photography, including The Ongoing Moment by Geoff Dyer. It was embarrassing how little I knew of the photographers he mentioned. Steichen, Stieglitz, Strand … they were just names on a page. Dyer convinced me that this ignorance should be corrected. And so, here I am, filling the gaps in my knowledge one post at a time.

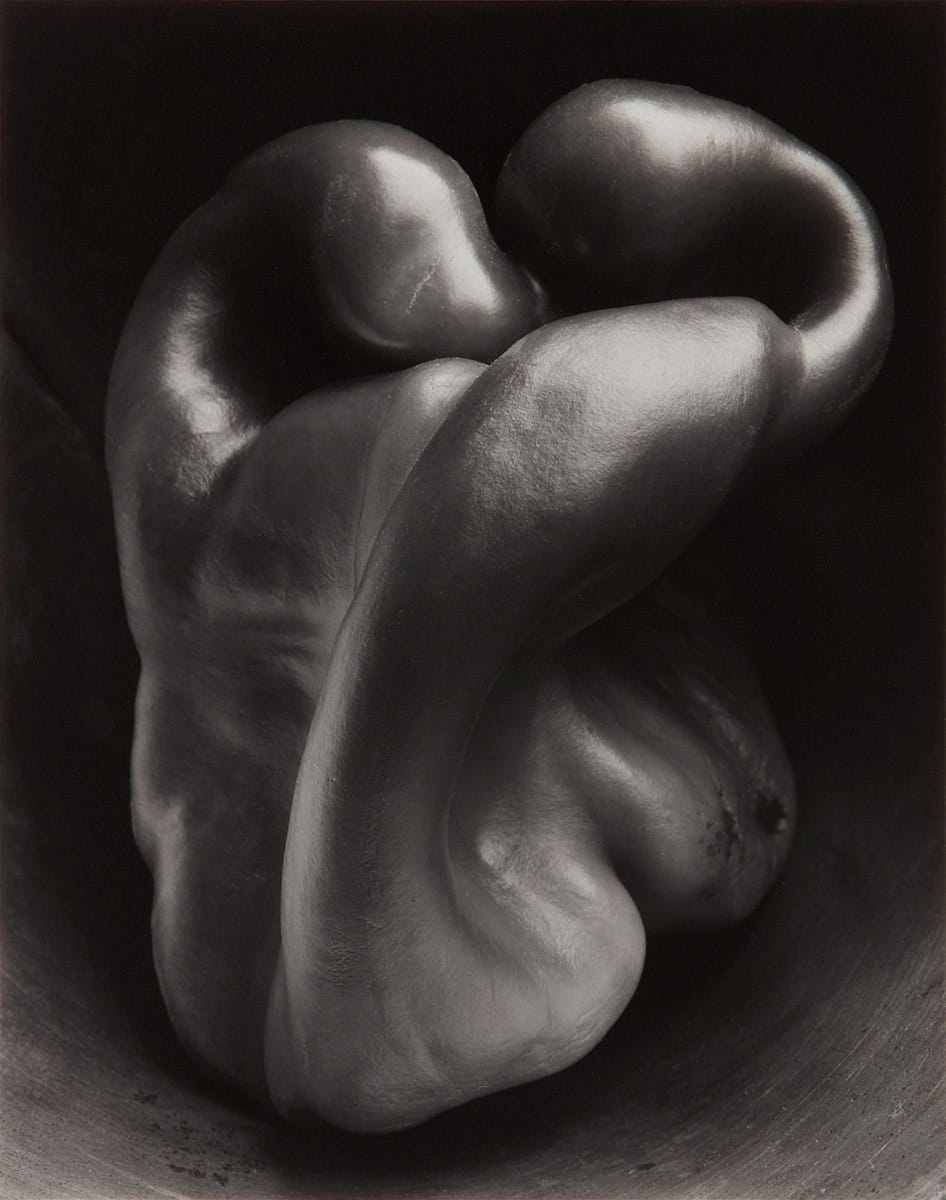

The most intriguing of Dyer's chapters was the one about Edward Weston, a pioneering modernist from the first half of the twentieth century. Weston passionately believed that the form of a photograph is as important as that which is depicted. His most famous images, those you see first on a Google search, are of fleshy peppers and sculptural shells.

However, such formal innovations do not interest Dyer:

Whatever their importance in the history of photography, I can’t muster up much enthusiasm for Weston’s endless grocery store of forms: the Lisa Lyon pepper, the brain-stem cabbage, the earth-from-outer-space onion, the cock-and-balls gourd.

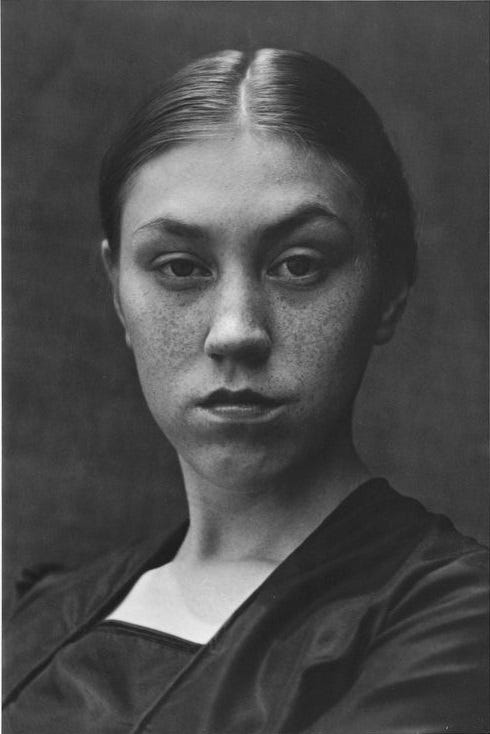

Dyer prefers to focus on Weston’s photographs of women. Particularly from 1923, when Weston walked out on his wife and four children to live in Mexico with the Italian actress-turned-photographer, Tina Modotti. This reveals much of Geoff Dyer's own preoccupations. He is a louche writer and a bon vivant. He loves the seductiveness of Weston’s life by the pool as much as his mastery of shadow.

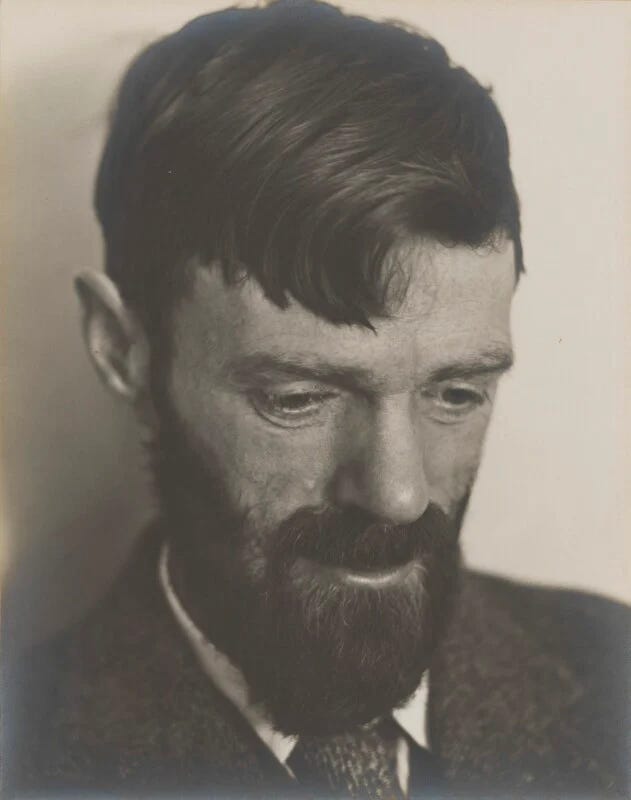

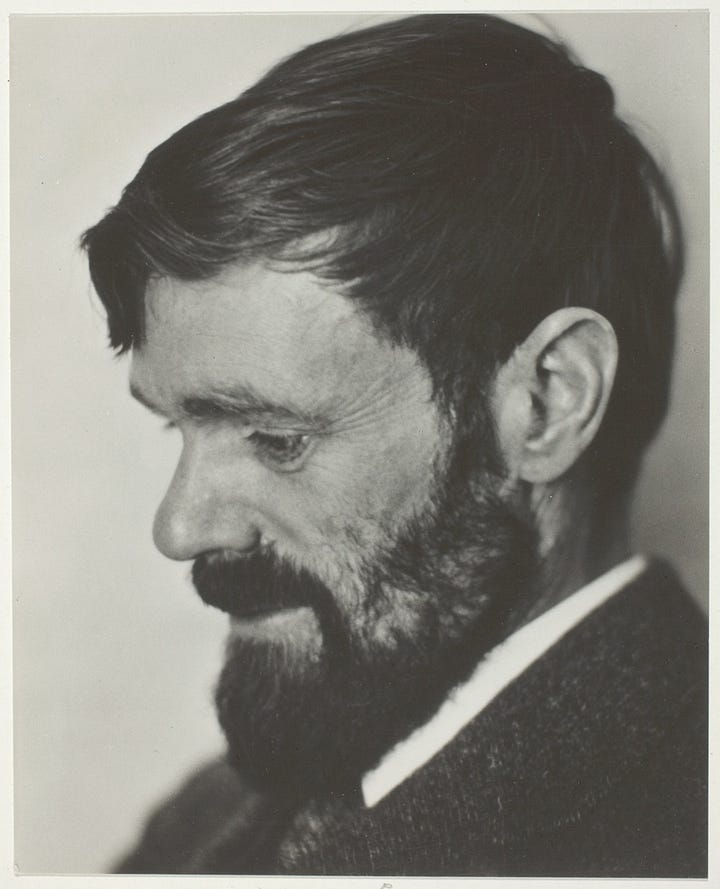

As a teenager, Geoff Dyer was obsessed with D.H. Lawrence. He discovered that Weston had taken two (oddly introspective) portraits of the writer gazing downward. It occurred to the young Dyer that there was an artist behind the camera, sparking his interest in photography. D.H. Lawrence was Dyer’s route to Edward Weston, just as Dyer is mine.

Despite (or perhaps because of) his sickliness, Lawrence was obsessed with vitality. He took his German wife’s interest in Lebensphilosophie and turned it into a call for capital-L Life. You can see it in the extraordinary essay Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine, written around the time he met Edward Weston in Mexico. It’s similar to George Orwell’s Shooting an Elephant, except vastly more deranged.1 Indeed, it’s the kind of essay that might make you worry that going for a jog will turn you into a fascist.

With Edward Weston, such worries recede. With Weston, vitality is channelled into art. He moved to Mexico not just for the tequila parties but for the sun that allowed him to “stand the devitalizing darkroom hours."

Weston’s Daybooks show the intensity with which he viewed his art:

My work is never intellectual. I never make a negative unless emotionally moved by my subject.

and

My true program is summed up in one word: life. I expect to photograph anything suggested by that word which appeals to me.

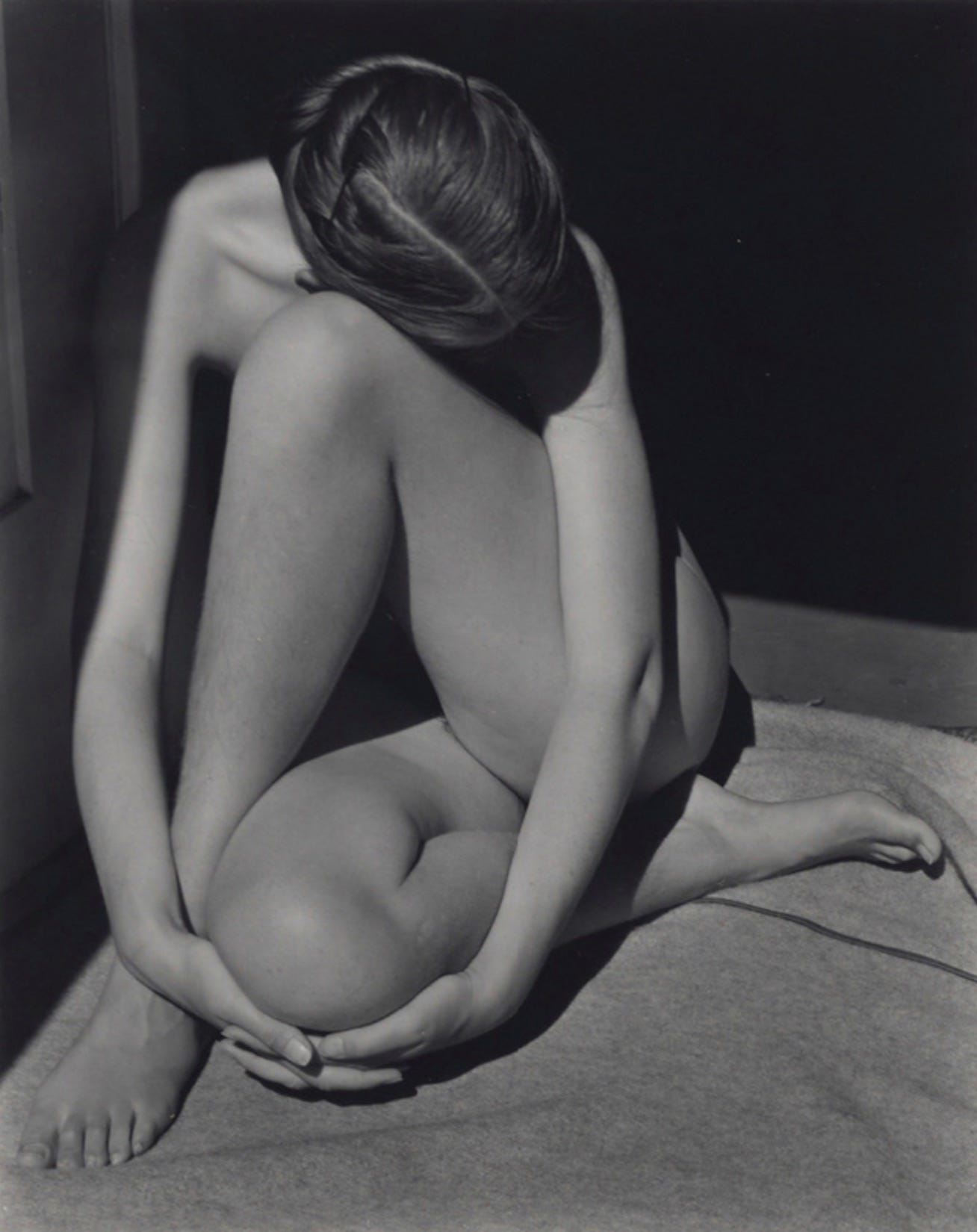

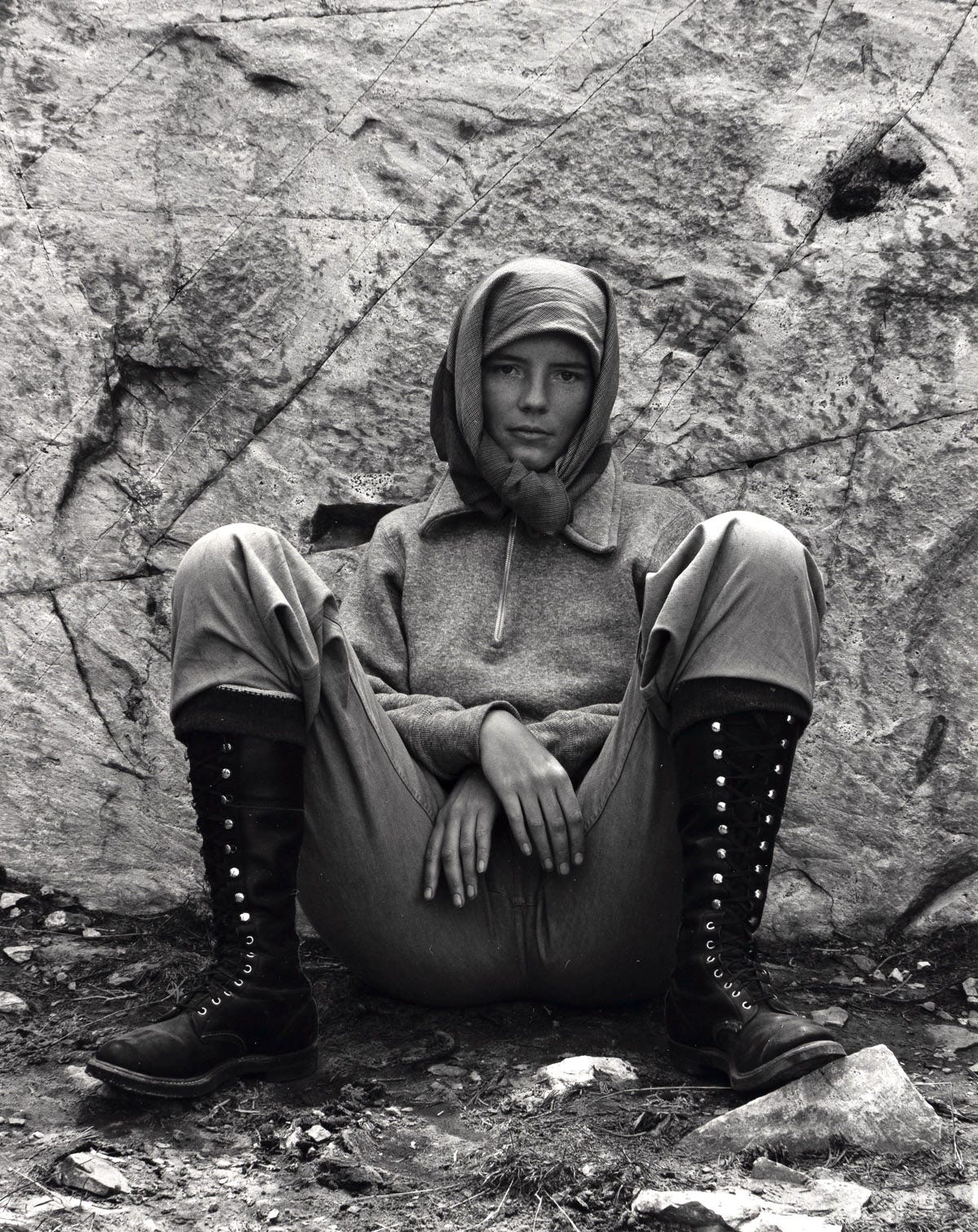

It’s true. His photographs are alive. Even when his women are clothed, as in this incredible photograph of Charis Wilson, so much vitality is contained.

Wilson and Weston fell for each other when he was 48 years old and she was 20. Despite the age difference, they formed a fruitful creative partnership. She wrote that he “made a model feel totally aware of herself. It was beyond exhibitionism or narcissism, it was more like a state of induced hypnosis, or of meditation."

Perhaps the real difference between the vitality of Edward Weston and that of DH Lawrence is in how that vitality is projected. Lawrence viewed life as a contest.2 He didn’t see any harmony just an unremitting process of subordination. By contrast, Weston’s vitality came from his attempt at self-overcoming. He writes:

It has come to me of late that comparing one man’s work to another’s, naming one greater or lesser, is a wrong approach.

The important and only vital question is, how much greater, finer, am I than I was yesterday? Have I fulfilled my possibilities, made the most of my potentialities?

What a marvellous world if all would, — could hold this attitude toward life.

With Weston’s advice in mind, the embarrassment I felt at my ignorance is a positive thing. I am better than I was yesterday. That is the source of vitality, constantly asking that question: What can I do today?

Lawrence’s essay ends with a call to subordinate ‘lower’ creatures and races:

Vitality depends upon the clue of the Holy Ghost inside a creature, a man, a nation, a race. When the clue goes, the vitality goes. And the Holy Ghost seeks for ever a new incarnation, and subordinates the old to the new. You will know that any creature or race is still alive with the Holy Ghost, when it can subordinate the lower creatures or races, and assimilate them into a new incarnation.

From the same essay:

Life is more vivid in the dandelion than in the green fern, or than in a palm tree.

Life is more vivid in a snake than in a butterfly.

Life is more vivid in a wren than in an alligator.

Life is more vivid in a cat than in an ostrich.

Life is more vivid in the Mexican who drives the wagon than in the two horses in the wagon.

Life is more vivid in me than in the Mexican who drives the wagon for me.

[…]

All this in terms of existence. As far as existence goes, that life-species is the highest which can devour, or destroy, or subjugate every other life-species against which it is pitted in contest.

try these ladies: Mikiko Hara, Rinko Kawauchi, Miyako Ishiuchi, Yurie Nagashima

I have written a little about the Daybooks and Weston a while ago. It‘s great reading your angle, because it is always different. Looking forward to Strand, Steichen and Steglitz (latter is on my list too!) =)