Interview with Alan Dimmick

A chat in the pub with the photographer of Glasgow's lost moments

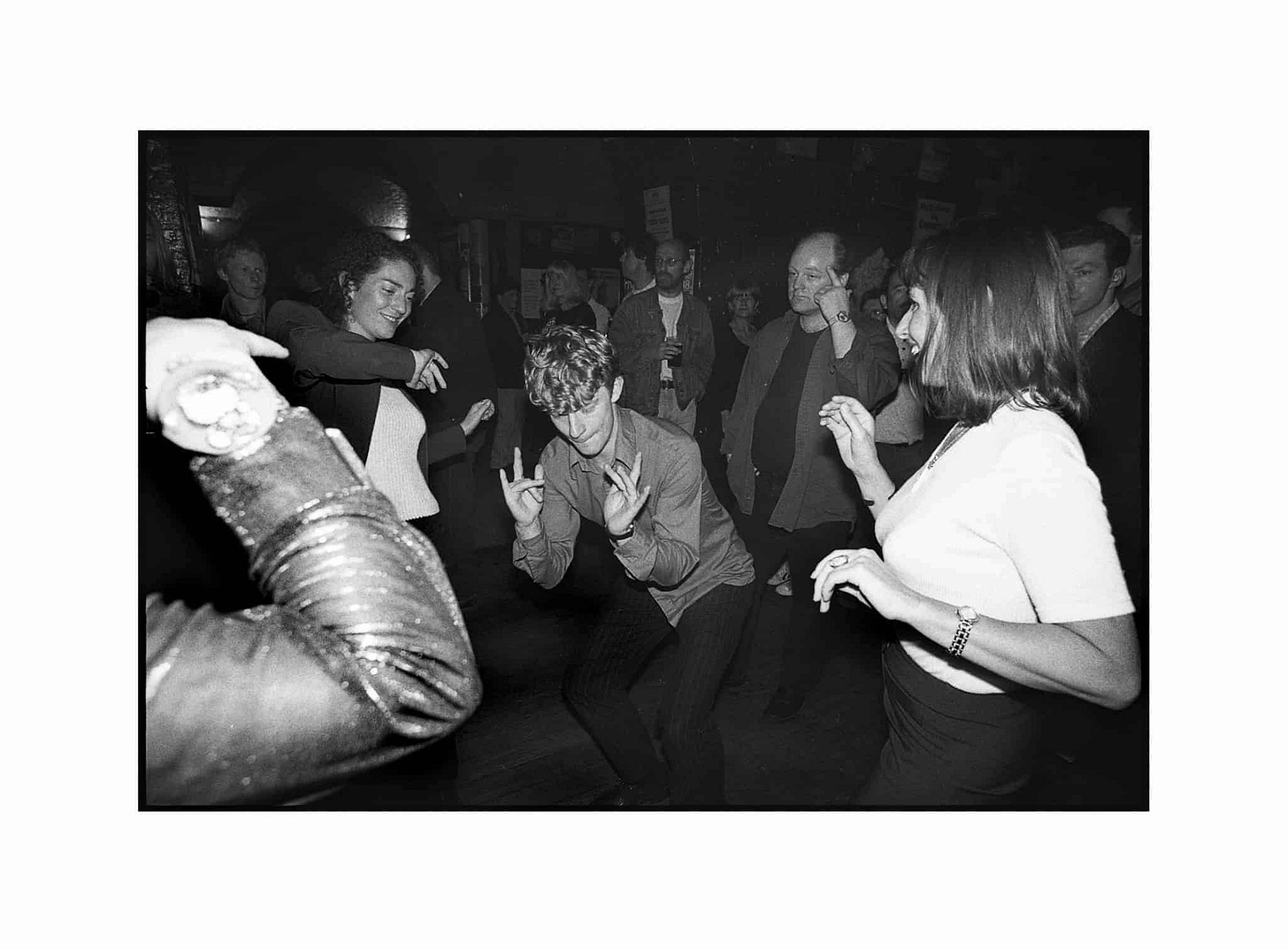

When I wrote about street photography last week, one of the people I had wanted to include was Alan Dimmick. Dimmick is a local legend for documenting the Glasgow art scene and I assumed I would find plenty of examples of it amongst his extensive archives. But there was very little that looked like typical street photography.

What I did find was powerful images of a lost world. Dimmick captures the poignancy latent in the medium. Stripped of colour and slightly grainy, he gets closer to how memories exist in the mind.

Dimmick's photographs are all taken with the same camera1 and are processed at home. This gives the images a consistency that makes it difficult to tell what year they are from. Only the changes in fashion or the lines on the face give any indication.

Neil Scott: When we talked about my article from last week you said you don’t really use the term ‘street photography’?

Alan Dimmick: You've got to remember that I've been doing this for so long now and that term didn’t exist when I started. I looked on the internet yesterday and you can now send away for a Street Photography pack. You get a Jiffy bag with a book on how to photograph strangers, some fancy film, and an overpriced camera.

For me, the composition has got to be right. You can take an image where the composition might not be that great and it can still be a strong image, but that's not good enough for me. I'm obsessed with trying to place things in the right position.

A lot of your photography seem spontaneous.

It might seem spontaneous, but my brain's still going crazy when I'm trying to take it, making 5/6/7 decisions in a split second.

How much of your photography is done by instinct at this point?

Instinct's a funny thing. When I was at college and I got into second year, I spent a lot of time in libraries, looking at books of different photographers. I was reading about the laws of composition, what you're supposed to do, what you shouldn't do. Around 1980, it seemed to mesh really well and I'd be showing my tutors these photographs and folk in the class were going: “why are you doing that? Why are you putting that person there?” And it was really hard to explain to them. But saying it's instinctive is a bit of a cop-out. Because I absorbed myself in photography, it was like osmosis. The rules of composition started to kind of sink in, though I often break a lot of rules just for the sake of it.

Roland Barthes, in Camera Lucida, uses the terms Studium and Punctum to explain what makes a photograph compelling. Studium is the setting of the image, the background. Punctum is the thing that arrests the eye.

Take this photo from 1979. The studium is the band and the fun day out for old folk. The punctum is the look of concern in the face of the guy in the wheelchair on the right.

I was doing these photos for the Boy's Brigade. They went out to Erskine Hospital and I had to photograph them marching through the wards with their bugles and drums. And these old guys were entertained in some way. People are so much more interested in my older work, once you get to 1988, it's like …2

Do you think your photography has changed over the years? What's the difference? Are you better or worse now?

When I was at college I was quite cocky. I thought I was doing something that was different and had this hubris. I left college after having been top of the year and went straight into doing exhibitions. I thought “this is brilliant.” But then reality kind of kicked in: I had kids and was working in a restaurant.

I should have taken way more photos. Two weeks would go by and I wouldn't have taken a photograph. That couldn't happen now, unless I was in hospital. And even if I was hospital, I'd still be taking photographs … I think back to so many occasions that would've made fantastic subjects for photographs.

I was going to ask if you ever regretted taking a photo, but it sounds like you regret not taking them.

I now go home if I've forgotten my camera. If you want to be a photographer and you don't have your camera, you're wasting your time. If I miss a photograph, I've got a sketchbook and do a drawing of the scene. Quite often the drawing's so bad that I tell myself the photo wasn't worth it. But missing a photo upsets me for a full day ... the drawing is therapeutic. But I'm not going to exhibit them.

It sounds like a good exhibition ...

Maybe when I'm dead.

You have a distinctive look in your photos. To what extent is that because of the equipment and processing rather than just being your eye?

Sometimes if I've put my camera down in a pub and gone to buy a drink, quite often the next day there's two or three frames and I wonder “did I do that?” In the book, there are two shots that I think Charlie Hammond took. I would hope I can tell. Consistency is important for me.

I think, like me, you are curious about reality, you like capturing it and want to see it again.

I do like revisiting images. The contact sheets are a really interesting thing because it shows the progression of what you were thinking that day.

Do you feel photography is like hunting?

Not really. I am not much of a predator. I prefer to observe rather than hunt.

I am fascinated by the relationship between photographer and subject. Joel Meyorowitz says people never got annoyed with photographers in the fifties ...

In the forties and fifties people were almost oblivious. There's a YouTube video of Henri Cartier-Bresson doing this magic dance around people. He's totally invisible but only because people are oblivious.

Do you have any tips for being invisible?

It's hard.

Do you know Simon Murphy? He has this amazing relationship with people in Govanhill. Apparently he talks to them for 10 minutes before he even gets a camera out.

You end up getting to know these people, talk to them for ages, and don’t even take any photos.

Some people get really uncomfortable and tense up when you take their photo. You can see it in the eyes.

I sometimes photograph people that are quite awkward, but I like the awkwardness. Not awkwardness in a way that's going to make them look stupid, but I'm very aware of what people do in front the camera. As soon as you tell people to do something, it falls to bits completely.

I feel photography is not about so much about the photos you take, but the photos you select. That's what makes the photographer good.

I like editing and I'm quite good at it now. When I look at contact sheets and I've made marks around ones I like two frames along and there's a photograph that's five, ten times better. And you think, 'Why did I completely ignore that?' That's down to experience. A lot of people enjoy photography, but they don't know how to edit, especially people with digital cameras. They'll get huge amounts of photos and they'll get confused. There'll be too much to look at.

And what is your hit rate? If you've got a film of 36 photos, how many would you think on average would be usable?

It can vary between 4 and 12 or 15. I can usually find something. I buy 20 rolls at a time for £130. I don't mind buying them. When I was at school I couldn't afford film and my teacher used to give me this Russian cine film that was really bad quality. But it didn't really matter, what was important is that you got to put film in your camera.

So you wouldn't go totally digital?

Well, all my commercial work is digital. Hundreds and hundreds of thousands of photographs of artwork and of God knows what … but no. I really like the consistency of what I've done. I love that one lens. I love the film. I love the camera. For me it is — it's so corny to say this — but it is like an extension of my hand. I know exactly what it does, and it's got a really good viewfinder.

And when you finish a film ...

I process it straight away. I'm in the dark room, processing it with all the chemicals. I'll let it dry overnight and then I'll put the film in the digital scanner. I use digital contact sheets now. Sometimes I go to the darkroom to do the print. It's a nice mix between film and digital.

Your son, Alasdair, has started exhibiting his photos. How does that feel?

It's good. He's quite like me in some ways. Julie [Alasdair's mum and Alan's ex] says he reminds her of me when I was younger. The way he talks to her now is quite idealistic. I was probably a bit like that.

I was looking at the photograph you posted on Instagram today of Laura. Could you explain why this is a good shot?

I was up to my neck in water. I like that she's so close in the frame and how the hair is hanging out of the swimming cap. There's something really odd about the idea that she's floating by. The rule-of-third thing is obvious, but I like the way that it does look like she's moving by.

Do you place any stock in what people ‘like’ on Instagram?

People just want to see human faces — or maybe a cat — but up close. Your face would be very successful. My sister saw that image of you at the private view and said 'who is that?' She thought you were so exotic.

People say photographers are outsiders. They're always looking in, you often don't know what they look like. But you've got quite a lot of self-portraits ...

It's funny you say that because I used to do a lot more of them when I was younger. I need to get some more taken.

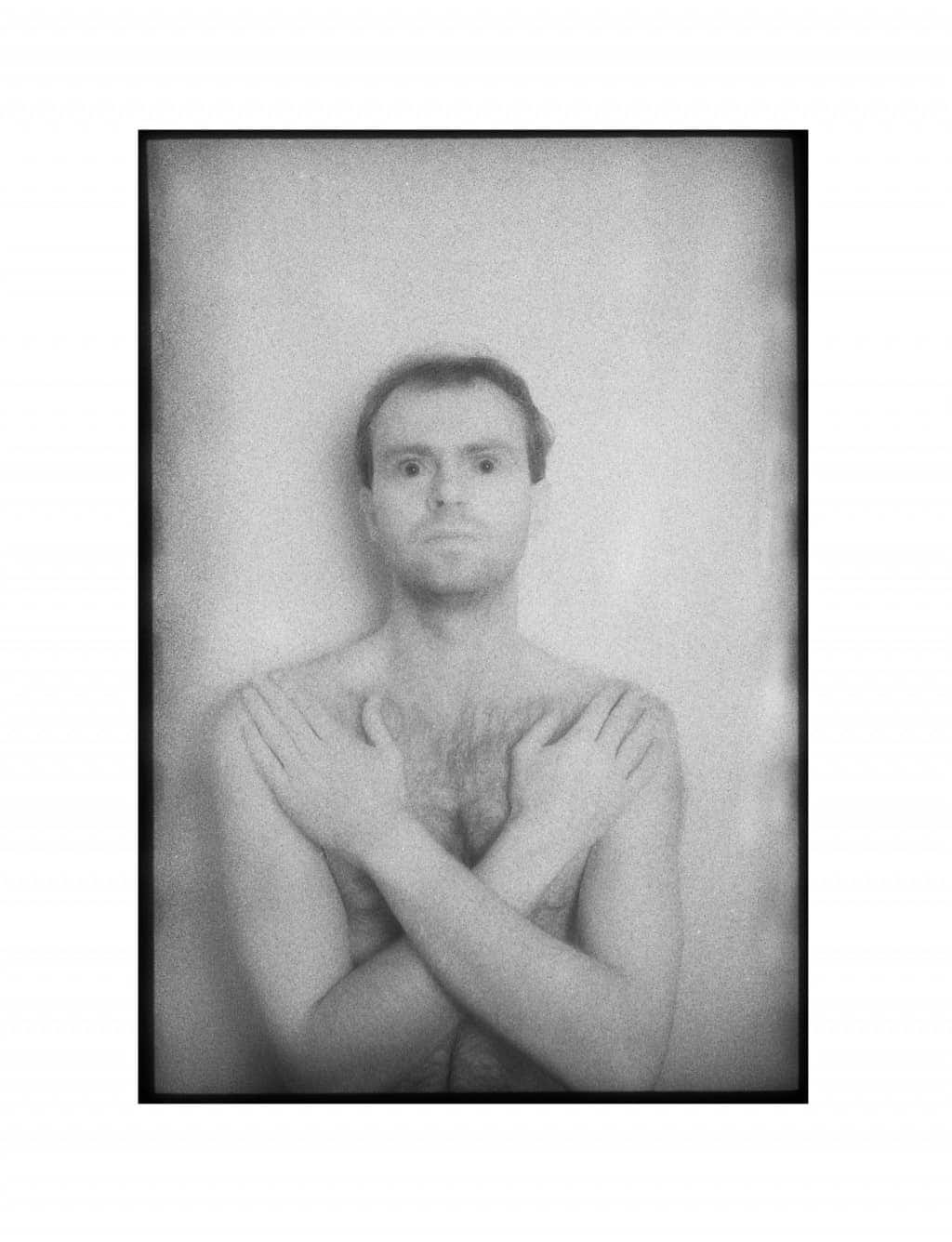

There are some good topless photos of Alan Dimmick …

The topless ones are ludicrous. They were for a college project where I took a photograph of myself with ultraviolet film that penetrates the skin by a centimeter. So it was a medical thing, but I ended up looking like Noserfatu in his tomb.

Or Chewbacca …

Ha ha, yes.

Were you an outsider in the Glasgow Miracle days? You were ten years older than most of the artists.

I was always aware that I was a bit older but, like my Mum before me, I don't find it difficult to talk to people. I think if you went somewhere and you just crept around the photographs wouldn't be any good. I like the interaction. It was very common for me to chat — like we are now — and then I would just take a picture at random. It's quite a rude thing to do, but thankfully most people put up with it.

You started taking photos a time when fashions really changed, suddenly there were punk rockers that looked incredibly different from hippies ...

They were quite scary.

… whereas now it doesn't seem like we have trends in quite the same way.

I used to be aware of short-lived youth fashions. Ken Russell's a great example of that. He took photographs of these Teddy girl gangs of London. They quite often have canes or umbrellas. He did a great job of photographing that. But it's how to edit it after and how to get these photographs together in a set that can be saved. Most people's photos, the majority of photographs that young people take now, will probably not be around when they're 60.

Are you nostalgic for the past? How has Glasgow changed in your lifetime?

Oh, it's changed a lot, but nostalgia is quite insidious. When you get older it's very easy to spend time thinking about times in your life when you were younger and you had your life ahead of you. It's easy to see them through rose-tinted specs. But I would go around the Barras when I was 25 and buy up photo albums of people because I knew they were going to get thrown out. So, for me, it's a bit more than nostalgia. I think it's important to keep these things safe.

An Olympus OM-1. He has 8 (eight!) of them because they keep wearing out.

I originally put the word ‘meh’ to represent Alan’s expression of public lack of interest, but I don’t think he would ever use this term. He later clarified that this was an exaggeration and obviously some later ones not too unpopular.