Linder: Danger and Glamour

A conversation with the artist about glamour, punk, and galloping consumption of images

Punk burned out quickly but was transformative for those who were there. Linder, aka Linder Sterling (born Linda Mulvey in 1954) was in the audience at the Sex Pistols’ legendary 1976 concert at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, an event which inspired an entire generation of musicians.1 The spirit of punk said to them: you can just do things. Start a band, create a photomontage, write a zine, pick up a camera, perform a ballet, all of which Linder has been doing over the past five decades.

Linder has retained the urge to make radical, intuitive artworks. Her Hayward Gallery retrospective, Linder: Danger Came Smiling, is currently showing at Inverleith House and last weekend saw the opening of A kind of glamour about me, a response to the Neo-Gothic mansion of Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute. At 70, it feels like Linder is finally getting the recognition she deserves. I spoke with Linder as she was putting the final touches to her work in the lush surroundings of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

Year Zero

Neil Scott: This exhibition has come from the Hayward Gallery, with all its Brutalist architecture, to the beauty of the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh. How has this change of setting affected the show?

Linder: Visitors will see a different narrative here because we’re working with a Georgian family home built in 1774. The proportions of the gallery are different. We've left some works out and added some new ones. There are portraits of me out in the garden from less than two weeks ago. But it feels different because we're away from London and in Scotland. The word glamour has always been ascribed to Scotland. It's a very glamorous country in all meanings of the word.2

Brutalism and punk share a Year Zero philosophy: destroy the old to remake the world from scratch. You moved to the country a while back and seem to have become a hippie in recent years …

Inevitably! The hippie movement was also extraordinary. Just seeing Beatniks on protest marches in Liverpool as a child gave me the idea of using glamour and language to affect social change.

Do you think punk has been invalidated?

People always ask if punk can happen again. But you have to look up at the landscape upon which punk stood to really understand it. Rather than spiky hair and safety pins, you have to really look at Britain at the time, a Britain that was in crisis. So when people say, "Could it happen again?" I usually say no. But more and more, it feels like punk might happen again. It would have nothing to do with safety pins and spiky hair. It might have a different dress code ... but I think the time is getting very nigh for something as potent and oppositional as punk.

We had one punk on the street where I grew up and it blew my mind that someone could look like that. Do you think we are living in the world that you, the punks, created with the explosion of individuality?

Far more! All of us were attacked at some point because we dressed differently. Not just verbal, but also physical violence. It was worthwhile, thankfully. Maybe it was easier to shock then, but the kickback wasn't as personal. Because there was no internet, we didn't have the abuse in our houses. Looking back it was like an age of innocence.

After Post-Punk

Are you still in touch with people from the punk era?

I am in touch with quite a lot of them. Many of us never made any money and ended up working for the post office or in factories. There weren't that many success stories. We became very invisible.

Howard Devoto is sometimes called the first Post-Punk for leaving Buzzcocks to form Magazine.

I remember. We were living together at that time. He was one of the first to jump ship. It was quite brave to jump ship.

Howard saw punk as a dead end?

It was getting diluted. I was reading a book at the time by George Melly called Revolt into Style. That was my road map. Melly describes all the steps of stardom and then how it starts to dilute fairly quickly. Because I was reading Melly, I had the sense that we were going past the purity. Inevitably, any mass movement becomes more and more diluted. It's fine. That's how culture happens.

You must never ever underestimate how quickly punk curdled. I saw the Sex Pistols in 1976 at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester at the time I was doing my third-year dissertation at Art School and a great tutor said: “Just write about what's happening and why you are wearing these clothes.” So I was writing my dissertation and I remember that by April 1977 my mother's housekeeping magazine had a pattern on how to knit a punk jumper for your daughter with tips on how to do punk eyeliner. I'm thinking "It's finished."

Size Zero

Do you think ideals of beauty in magazines have changed at all over the years?

I still don't trust advertising. Advertising is so conservative. They have more diverse bodies, but I'm never convinced it will be sustained. In the latest collections, they were back to size zero models again after having had the token voluptuous model on the catwalk.

Have you seen anything beautiful recently?

The gardens. Every flower in the garden. Every bee in the garden. Nature's beauty, really. We need more safe spaces and the garden here is an important safe space. I walked here at night and felt protected by the garden, which may be overly romantic, but my nervous system felt relaxed. It didn't have any sense of danger coming, smiling or otherwise.

The Ethics of Photomontage

I wrote about Richard Prince and rephotography recently, which is hugely successful in the art world, but widely despised in the photography community.

And rightly so! Even though I, too, steal photographs.

What is the difference with photomontage? You don't seem to come in for the same criticism as he does.

No. Because I'm using ephemera which is about to be thrown away or things I've just found in a junk shop. A lot of the material I work with is seen as culturally worthless. I look to elevate it in some way. With Prince, he has a big, seamless surface. Whereas mine have these cuts going across. They're like transplants or grafts. What I do is a form of grafting from popular culture. I'm always rooting through magazines and that which is being discarded, trying to find that one face or that one interior that excites me.

You've never had one of the photographers of the topless models come and say: "Oh, that's actually one of mine."

No, although with pornography, I would always have loved it if one of the models had got in touch and said: "This is me, this is my photograph." Because they always had to have a fake name. And still do... except for Mia Khalifa. Crash Magazine in Paris asked me to do a spread, and I said: "I will only do a spread about Mia Khalifa." We got to work together with the photographer Hazel Gaskin. That was the first time I'd worked with someone in the sex industry that had a name. We became friends and I learned a lot from Mia about the legalities of that industry.

AI porn is doing something similar to photomontage with deepfakes.

Oh god, anyone can do it! You just push the “no clothes” button. Young women's lives are being destroyed by this. They’re in that tender age of adolescence and suddenly their face is plastered onto a body and everyone—the whole village, the whole town, the whole whatever—is seeing it. It’s deeply distressing.

Is there any work from your back catalogue that you've wanted to remove?

No, it's simply space. It was pure practicality ... there was no moral judgment.

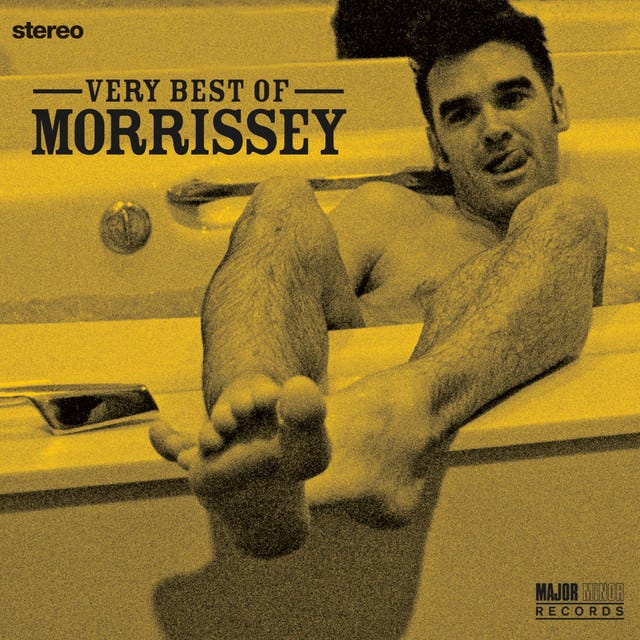

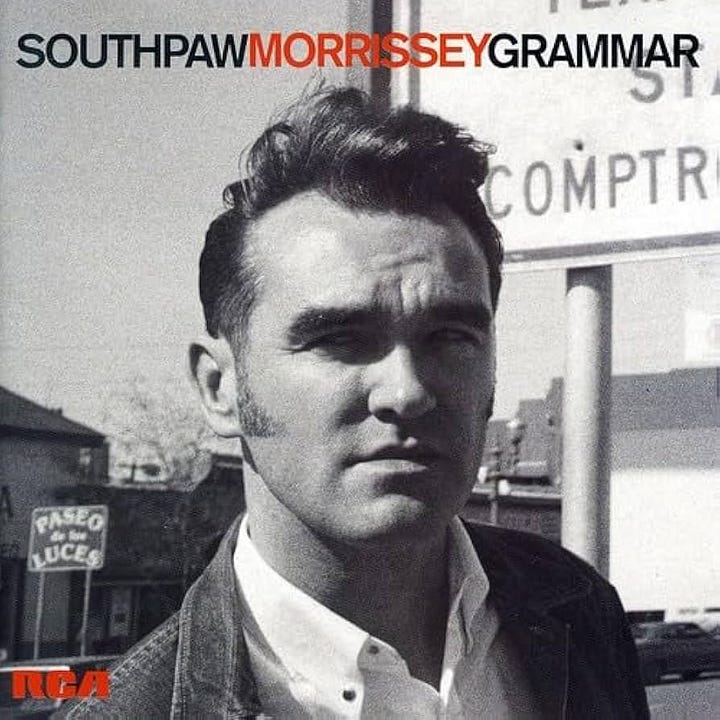

I was a little annoyed when Morrissey removed Ordinary Boys and Roy's Keen from the remastered versions of Viva Hate and Maladjusted.

Oh, I know! When an artist does that, you think: "Why did you take those tracks off?" But it happens. It's either practicality or it seems the right cut at that moment in time.

It's nice in a way because the artist is taking ownership of who they are now rather than serving a version of themselves from the past. I love that there is continuity in your work, but also freedom within that continuity.

Very much so. Yes, I started drawing a lot more recently. I perform, I work with fashion designers ... I have a good time. I'm really lucky at age 70 to still be working. Maybe even harder than I worked in the past. In the past, it was difficult because not a lot of people knew my work.

So you haven't got a big studio full of people churning work out?

No, it's just me and a scalpel and some glue. I have to cut. I've got such a skill set now. It's like being a heart surgeon I can really cut so accurately that people think they're prints. But if you look closely, you can see the edges.

You are a kind of a magpie finding treasures, yet we live in a hugely visual culture where one could easily be overwhelmed by stuff.

I don't look at a lot of stuff online. I don't scroll. It has to be a physical cache. It has to have that weird smell of must. It's hard for a rectangle of glass to pull my attention. I don't want to look at it. I don't want to spend my time rubbing my finger on glass.

DIY

There have been a lot of exhibitions about the eighties recently, such as Women in Revolt, which you were featured in. Do you have any theories about why that time is particularly interesting to contemporary curators?

It was one of the last periods in Britain where there was an aspect of DIY within the culture. There's not been such a mass period of people making their own clothes, making their own music, making their own zines. But there's always nostalgia around. When I was in the seventies, we were looking back at the 1930s. We can't help but look back to our origins.

It seems harder to identify mass movements now. Who knows what the mass movement was from ten years ago?

Yes, maybe people feel safer now not standing out.

What advice would you give those people?

Do whatever pacifies your nervous system. If you want to doom scroll, that's fine. But, for most people, those images don't leave their heads and they get more and more anxious. We say people consume. They consume images and they consume pornography. Well, both my grandparents died of what was called “galloping consumption” i.e. tuberculosis. What we have now is a galloping consumption of images. We say things like “food porn” and “interior design porn”. It’s this hypnotic rectangle of glass.

Every week the phone tells me how much time I spent on the phone and I'm like, "I know I did! I'm really annoyed about it."

Exactly. I've given you all those hours. People as young as 30 are having cataract operations when normally cataracts happen when you're 70 or 80. Their eyes are locked. They’re not looking around. That's a very stressful position. We are hardwired to be looking out to the horizon—looking for lions and tigers—but to fix them seven inches away is not good.

Photographing Morrissey

Apparently, it’s Morrissey’s birthday today.

It certainly is.

He is currently on tour. Are you going to get the camera out as you have done so many times before?

It could easily happen. It could. I was just going through the archive because Morrissey wanted certain photographs recently. Just looking at that time and when Morrisseymania was so intense, especially during the American leg of the tour. Just to see that phenomenon up close, just to see that passion from fans. I'm sure it still goes on for some groups. It definitely goes on for Morrissey.

There's an amazing intimacy in those photos. Do you think you can only have that with someone you are incredibly close with?

You have to be a friend. That's a lot of trust to have somebody just travelling with you all the time. But even with your closest friend, it's still very privileged to come in and take photographs of whatever you want, anytime.

I am fascinated by people who can turn it on, like Lauren in the garden earlier.

There's that confidence and that shape-shifting. It's glamour. It's a way of using glamour and flicking that switch inside.

Ego and the Self as a Found Object

You’ve said you’re camera shy, but you have had a lot of photos taken over the years.

It's good to be in the mood, though. I find it more difficult to take photos every day. But if I had to do a photo session, I'd really prep for a few weeks about what to wear, what posture to do, and just to get in the mindset. I respect the camera a lot.

With meditation we seek to loosen ego attachment, but at the same time, any artist who's going to put anything into the world has to have an ego.

Yes, you do need a really good sense of self, in a positive way. If you're not meditating then you can't understand that sense of purity: that beautiful quietening of the moment you get during or after meditation. There's a great clarity in making work that's far larger than oneself.

And does that change your view of yourself as a found object?

Yes, I think women can totally disassociate. It's not about leaving your body or being not present, it's a little trick of the glamour. You can stand outside yourself whilst being inside yourself. I know when it happens that I can feel it viscerally. I can't really articulate that, but it's a good sensation. It's like you are hyperaware that the tilt of a chin or how one's nail polish can affect things. It's the glamour.

Thank you, Linder.

Linder: Danger Came Smiling is at Inverleith House and in the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh until 19 October 2025.

A kind of glamour about me is at Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute until 31 August 2025.

Both shows are in collaboration with Edinburgh Art Festival.

Including Buzzcocks, Joy Division/New Order, Morrissey, Mark E Smith, John Cooper Clarke, Tony Wilson from Factory Records, and umm Mick Hucknall. The gig features prominently in Michael Winterbottom’s biopic of Tony Wilson 24 Hour Party People (2002):

The word glamour derives from the Scots word glamer was a ‘magical delusion’ that would affect the eyesight of those afflicted, so that objects appear different than they actually are.

Great convo :) cool to hear from an authentic punk

Fab. I love her work and very much enjoyed the exhibition at The Hayward. A great interview.