I am suspicious of writers who start their books with a dictionary definition of the idea they are discussing. It tells me that they can no longer float freely in the sea of language and need the dictionary as an anchor. That said, I never tire of hearing the origin of the word photography, coined by John Herschel in 1839, which means ‘drawing with light’.

Drawing with light is a beautiful description of how photography captures moments that would otherwise disappear in a flash. It’s a medium where even a snapshot can leave behind a trace of the impermanent. Yet, despite working with the impermanent, few photographers seek to embody that impermanence.

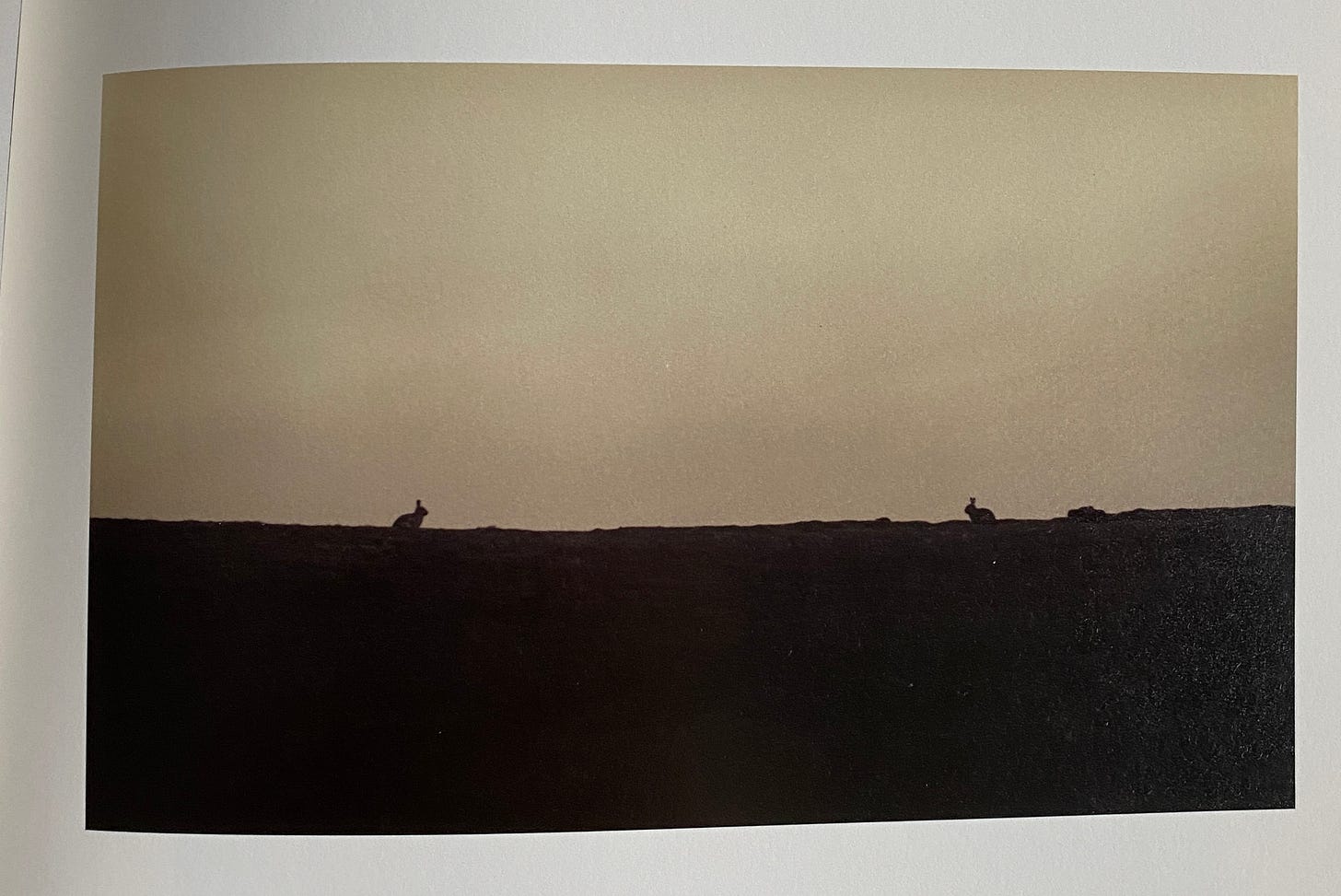

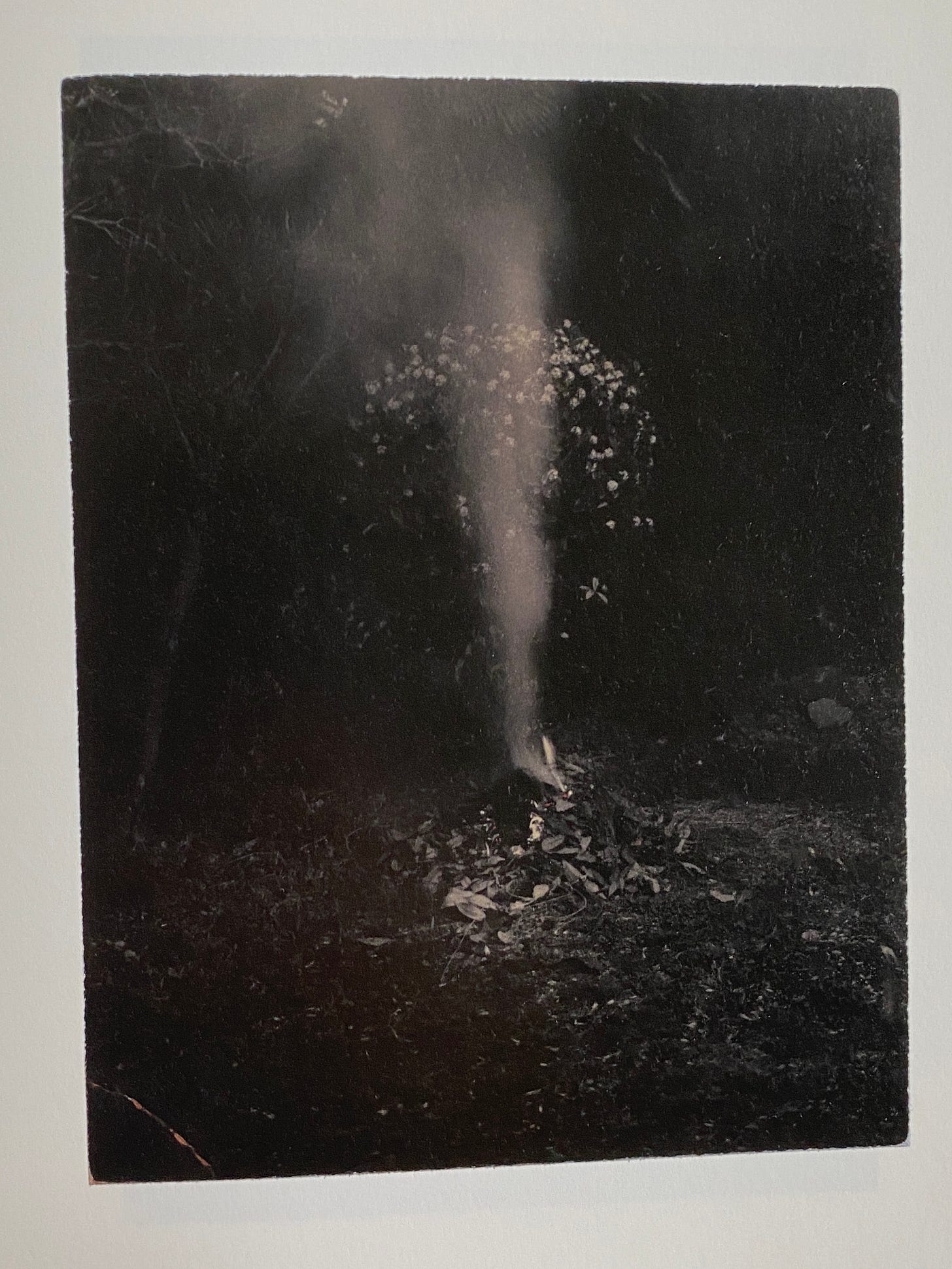

Masao Yamamoto1 (b. 1957) is different. His delicate prints show his hand in their rough edges and scratched surfaces. His subject is the flux of life, the constant growth and decay, the evanescent moments that disappear as soon as they arrive. The photographs in his book, Small Things in Silence, consist of natural scenes in soft black-and-white. They are also the closest I can imagine to Zen photography.2

Coincidentally, this week, I have been in the Far East. Not Japan, but near the UK’s most easterly point. While there, I tried to understand Masao Yamamoto’s photography. Not in silence, but through the untranslatable concepts in the Japanese language.

1. Iki

While China is difficult to grasp, many of us carry an idealised fantasy of Japan in our heads.3 This is partly due to Japan’s 250 years of voluntary isolation from the rest of the world, which ended as recently as 1853. This isolation led to a culture like no other, where samurai wore elaborate armour while the merchant classes were forbidden from appearing too showy. Iki was the result: a minimalist aesthetic of calculated simplicity. In Yamamoto’s photography, there is never excess and often a sense of omission.

2. Wa

Wa is the trait that we, in the West, traditionally associate with the Japanese. It literally means harmony and represents the prioritising of the collective ahead of the individual. Yamamoto’s photographs are full of harmonious balance: dark and light, yin and yang. Such order is an emergent property and never feels forced.

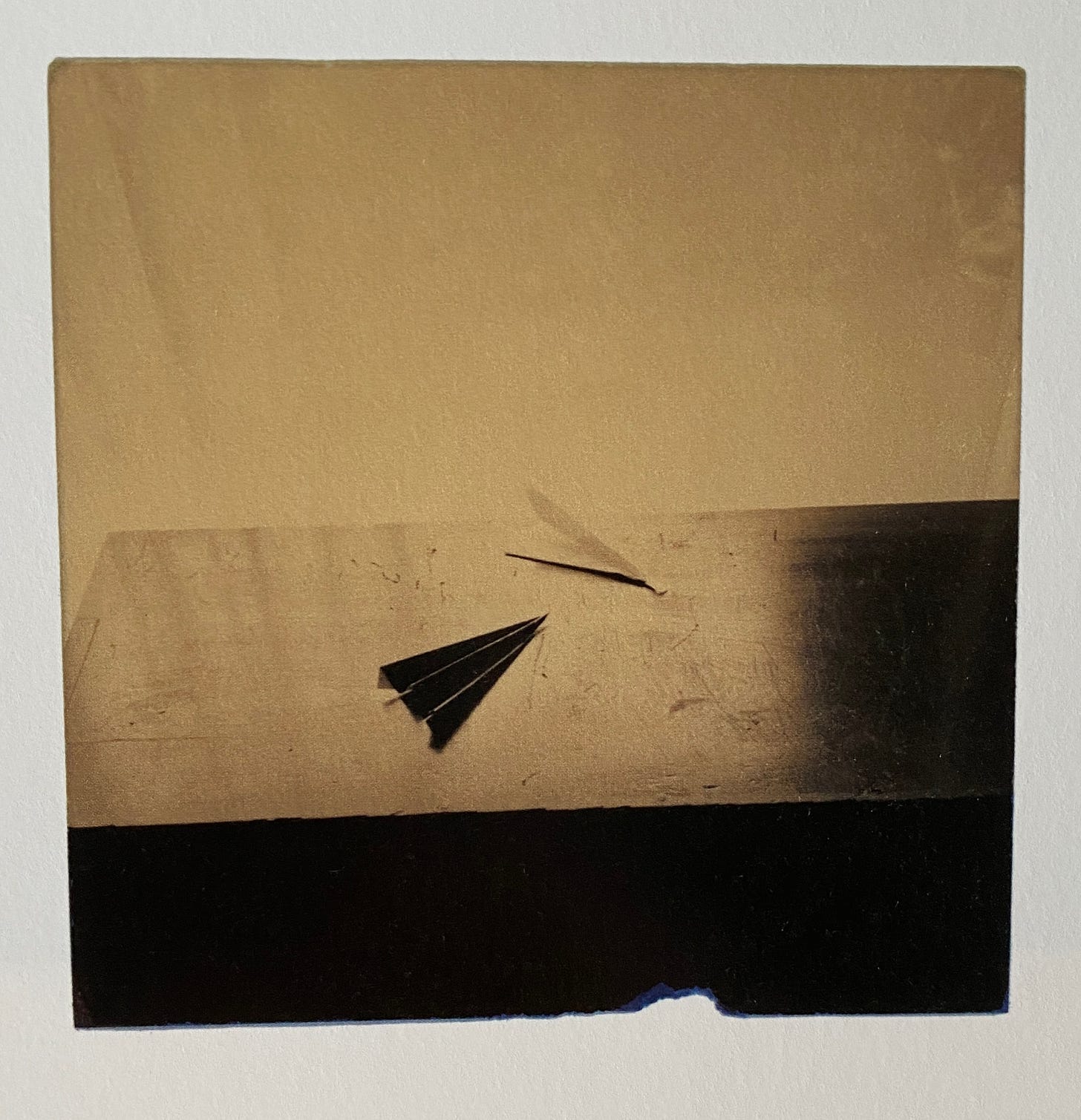

3. Wabi-Sabi

Wabi-sabi is perhaps the most familiar concept in this list and represents the transience and imperfection of all things. We might think of a Zen garden that has been raked into simple patterns or a paper aeroplane whose nose is bent after a crash landing. Yamamoto’s rough prints include imperfections as if they were memento mori.

4. Komorebi

Komorebi literally means “sunlight leaking through” and refers to how rays of light shine through leaves in a forest. It is a beautiful effect if you can take the time to notice it, though has become something of a cliché in photography. In Yamamoto’s work, the effect is enhanced with a waterfall and a group of bathers approaching the water. One can feel the flow of life, as in a painting by Vermeer.

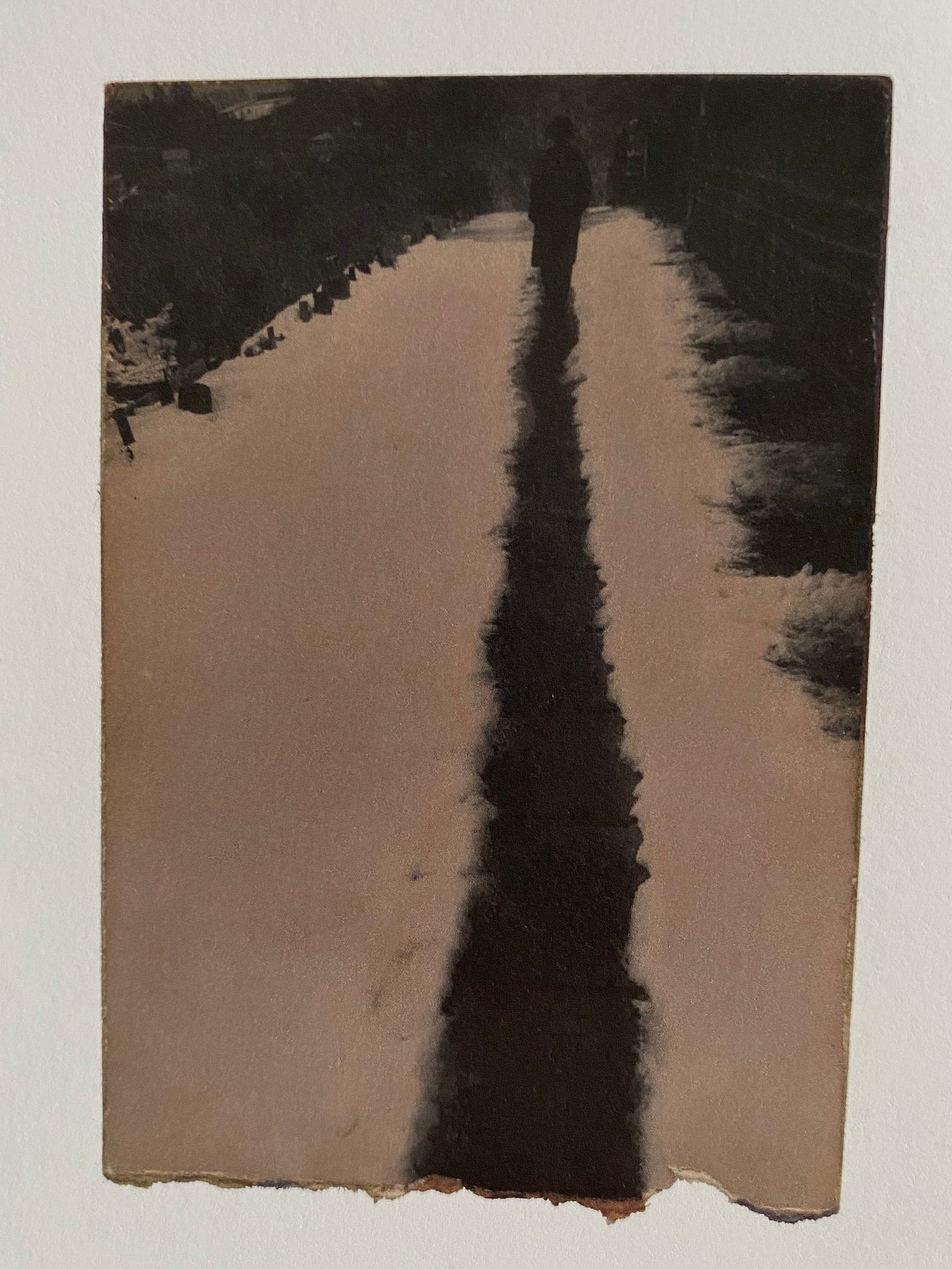

5. Kawa

Kawa translates as river, though it also implies flow, especially in Zen Buddhism. Indeed, one of Yamamoto’s photographic series is called KAWA=FLOW. For him, flow is the continuity of all things: the path becomes the figure which becomes the horizon.

6. Mono no aware

In writing this post, I was delighted to learn that the title of

’s design newsletter, The Pathos of Things, derives from the Japanese phrase Mono no aware. So what does it mean for an object to evoke a feeling? In the West, we have become accustomed to treating the world of things as disposable, dead. In Japan, a residue of the animistic Shinto religion which imbues inanimate objects with a spirit. One of my favourite bits in Mari Kondo’s minimalist book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, is when she thanks objects for their service before disposing of them. How wonderful the world would be if we filled our surroundings with soulful objects.7. Natsukashii

Natsukashii means nostalgia, but it is a happy nostalgia for time spent together. This is not melancholic but filled with gratitude: sentiment without sentimentality. In the following photograph, a child carrying a balloon or a kite skips cheerfully into the future, which feels like happy nostalgia to me.

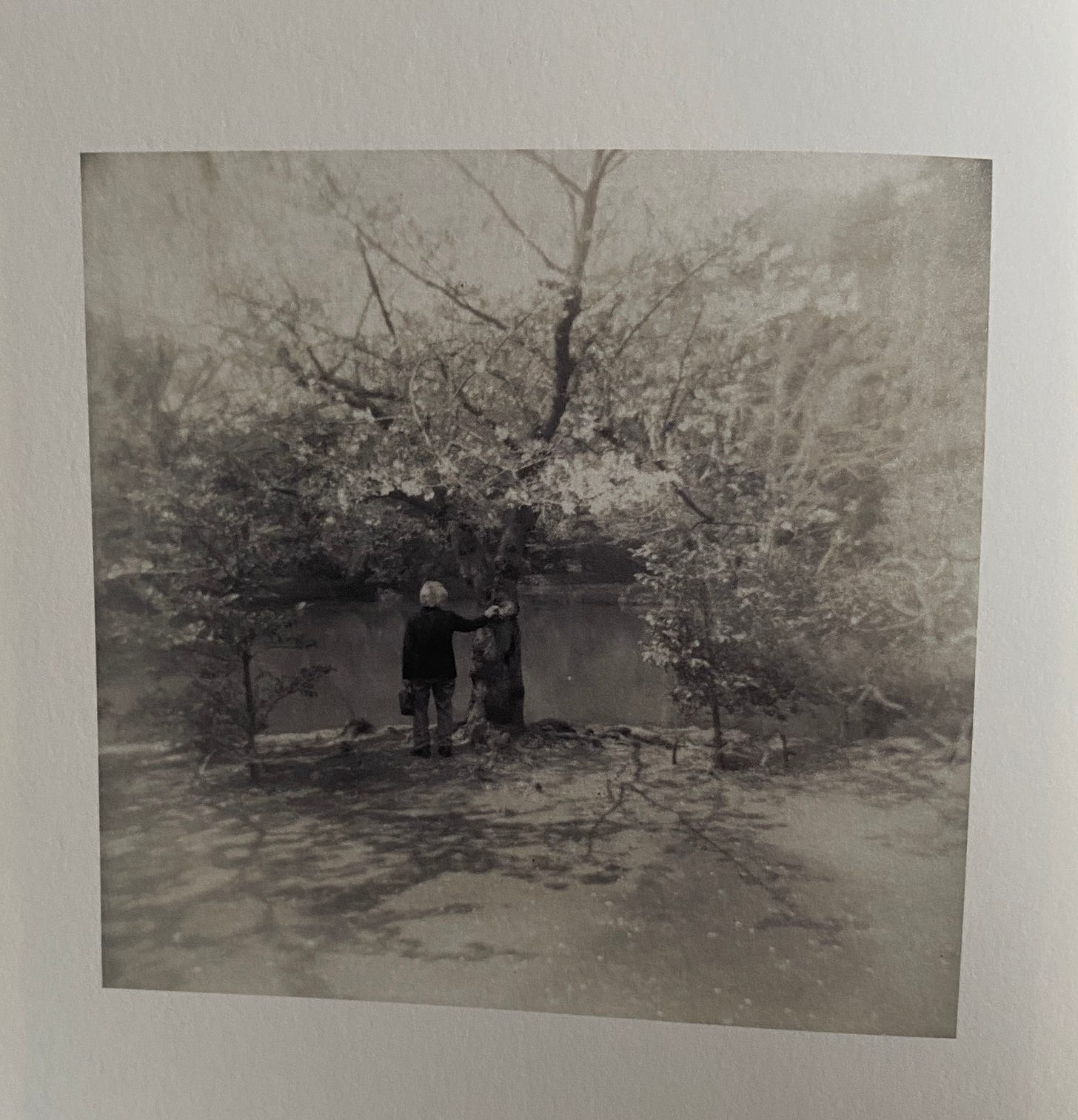

8. Shibusa

Shibusa is another subtle word from traditional Japanese aesthetics. Although related to Iki and Wabi-sabi, it tries to resolve qualities such as elegance and roughness, spontaneity and restraint. The related word Shibui refers to an understated beauty that increases with age. In this photograph of an old man gazing out at a lake, supported by a tree, I feel this sense of tranquillity.

9. Hara

Hara is a concept I first heard about from my yoga teacher, Kia Naddermier. It primarily signifies the abdomen but has a deeper meaning as the centre of your being. Listening to your hara taps into the wisdom of the mind-body: the fire in your belly and the intelligence that arises.

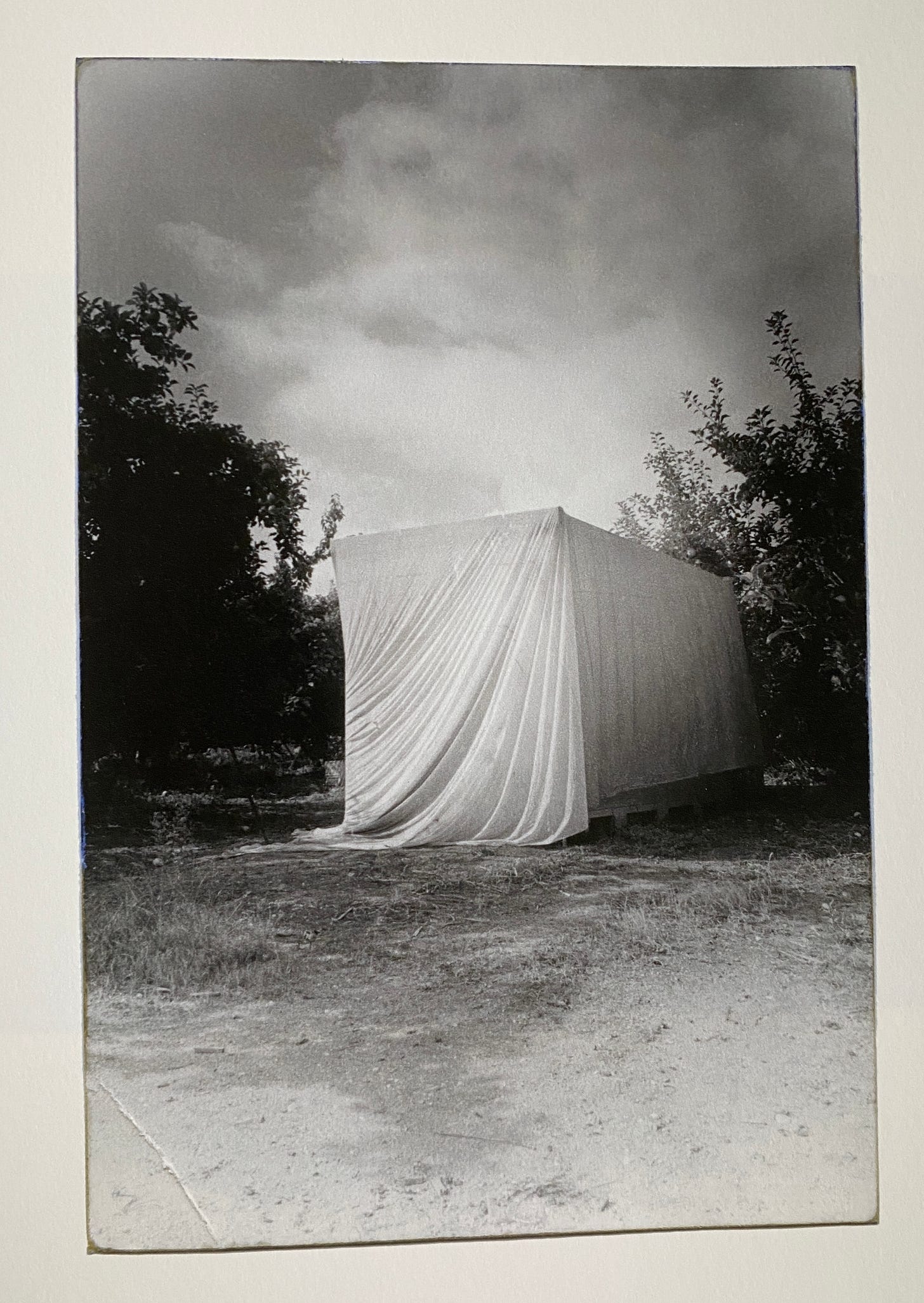

10. Yūgen

Yūgen, depending on the context, means “deep” or “mysterious”, but also refers to the beauty found in that which is merely suggested. In photography, as well as drawing with light, we might reflect on things that were lit hours ago. What still lingers of that light? Or, more literally, what lies under the sheet? In Yamamoto’s photographic koans, we can’t help but wonder.

A new edition of Small Things in Silence is due to be published in October.

The Japanese put the family name before the given name. For consistency with my project, I follow the Western convention.

As I was writing this, I saw a fascinating note from

highlighting the origin of the word “Zen” and how it helps us understand the difference between Eastern and Western ways of being in the world:Zen (Japanese) comes from ch’an (Chinese) which comes from dhyāna (Sanskrit) which all translate to “meditation” in English. If you go further back in time you get to the [Proto Indo-European] root dheie which refers to noticing (distinct from seeing). If you then proceed forward in etymological history down the English line this root gives us théa, meaning view. From here we get theōrós, a viewer, which births theōria, a viewing, which ultimately gives us theory.

While all of this is wildly speculative, it’s fun to imagine the developments that necessitated making such distinctions: seeing vs. noticing, a viewer vs. a viewing, a viewing vs. a theory. It’s also revealing that Eastern cultures evolved noticing into meditating and the West evolved noticing into theorizing.

Including me. I have conspicuously chosen the most ethereal words. The truth is that Japan is not all Zen Gardens and Geishas. Here are some less romantic untranslatable words I didn’t include:

Karuoshi = sudden death from overwork.

Tsundoku = to pile up books without reading them.

Kuidaore = to go bankrupt by spending extravagantly on food.

Hikikomori = people with severe social withdrawal leading them to become hermits.

Let me know if you have come across any illuminating untranslatable words in the comments.

Very interesting take on Yamamoto. The idea of having a work of art in your wallet is something that I find very interesting. One of the reasons that I like smaller photographs, rather than a 16" x 20" or bigger. Yamamoto's idea of having a small visibly 'handled' object, that can be held, studied and put away again till next time is wonderful.

Sadly, in his later work he has been making larger prints and they are much less interesting, perhaps because his galleries around the world demand them. There is something very strange about a series of bonzai photographs that are approximately 1:1, which of course no longer fit in your wallet and are no longer precious in the way that something is that you can hold and caress. One would have thought a bonzai would lend itself particularly well to wallet size. Sadly, in my view he has lost the plot a little. His earlier bodies of work are however among my favourites. He is a great printer and a great artist.

Love the post! Have been reading about these concepts as well. The untranslatable ones are interesting and brought a smile.