Roman Vishniac

Jewish photography and the Ordeal of Civility

At the end of last year, I announced that I wanted to focus on one thing in 2024. That thing was photography and has gone far better than I could have hoped. Thank you to everyone who has read, liked, commented, and shared.

I decided to write about photographers in alphabetical order, if only to add structure to the project, with a different letter each week. This is, unbelievably, week 22.

Of those I've covered so far, I noticed that eight are Jewish: Diane Arbus, Robert Capa, Robert Frank, Nan Goldin, Philippe Halsman, Helmut Newton, Man Ray, and this week's subject, Roman Vishniac. Over a third! This was not intentional—and may be totally coincidental—but I am curious if there is something in Jewish culture which predisposed them to photography.

I am not the first to broach this topic. Garry Winogrand claimed that great photographers were Jewish because they were "nervy, ironic, disruptive of artistic norms and proud outsiders."

Meanwhile, William Klein divided photographers into two types, Jewish and goyish, saying:

If you look at modern photography, you will find, on the one hand the Weegees, the Diane Arbuses, the Robert Franks—funky photographs. And then you have the people who go out in the woods. Ansel Adams, [Edward] Weston.

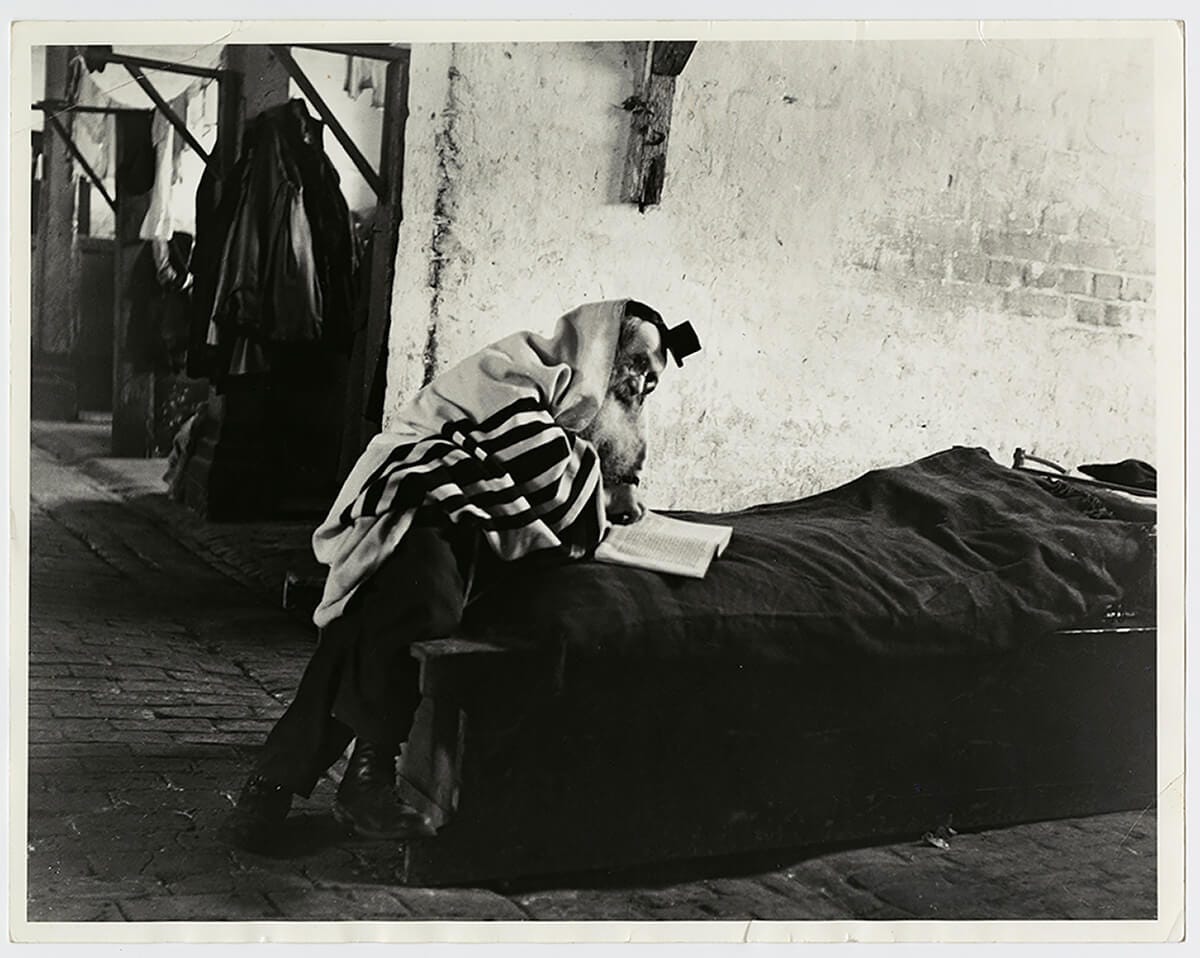

With Roman Vishniac, the question of Jewish photography is pertinent because he is the defining photographer of the shtetl (the insular towns of Ashkenazi Jews in Eastern Europe), capturing everyday life before they were destroyed in the Holocaust.

Vishniac himself was not from the shtetl. He was born near Saint Petersburg in 1897, the son of a wealthy umbrella manufacturer. As a child, he was fascinated by biology and photography and combined the two with the help of a microscope. The family fled Russia after the Bolshevik revolution, ending up in Weimar Berlin. There, Vishniac embraced a modernist aesthetic.

The rise of Nazism led to him getting a commission from a US relief charity to document the plight of poor Jews in Eastern Europe. The original aim of these photographs was to raise money from Americans, but after the war, the photographs came to represent an authentic Jewish culture as it existed before the Holocaust.

Vishniac's most famous book, A Vanished World (1983), presents the shtetl as being full of impoverished, observant Hasidim, isolated from the modern world. This was, however, only part of the story. Investigations into his archive by Maya Benton revealed that he was a “mythmaker” whose curation had skewed “the popular conception of pre-Holocaust Jewish life in Europe.“ Alana Newhouse sees it as being part of a drive towards sentimentalisation by “secularised, often prosperous Jews troubled by the sense that their hard-earned modernity may have come at the price of tradition and authenticity.”

For a shared identity there needs to be a shared story. With the Jewish people, our thoughts immediately turn to the Holocaust or the Old Testament. But in between, there were a thousand years or so of living as pariahs in Europe, a situation that only ended with the Jewish emancipation. Until recently, I'd never heard of this historical development, but it was hugely important and gives us some hints as to what might distinguish Jewish photographers.

Before the late eighteenth century, Jews in Europe had been second-class citizens. They were unable to vote or participate in politics. They were often confined to shtetls or ghettos. The emancipation allowed them to flourish, yet the atmosphere of the shtetl—an intimate world of argumentation and honesty—persisted in the culture.

The sociologist John Murray Cuddihy, author of The Ordeal of Civility, writes of the emancipation as a case study of culture shock. Suddenly, a familistic society found itself “in a world of strangers: the nonkinship, universalistic nation-societies of modem Europe.” Life in the shtetl was, by contrast, emotionally open.

Cuddihy quotes Artur Schnitzler’s The Road into the Open:

No Jew has any real respect for his fellow Jew … Envy, hate, yes, frequently admiration, even love … but never respect, for the play of all their emotional life takes place in an atmosphere of familiarity, so to speak, in which respect cannot help being stifled.

For Cuddihy, Jewish emancipation led directly to the creation of psychoanalysis, Marxism, and structural anthropology. In each case, a traumatic encounter with the rules of Western bourgeois life led to a universal insight. Cuddihy writes:

This importunate “Yid,” released from ghetto and shtetl, is the model for Freud’s coarse, importunate “id.” Both are saddled with the problem of “passing” from a latent existence “beyond the pale” of Western respectability.

Respectability means adhering to seemingly arbitrary rules. Perhaps the best illustration of the ordeal of civility is Curb Your Enthusiasm. Larry David is constantly pointing out hypocrisies in modern life. He disputes random people and their rules, then returns to the intimacy of his friends, Susie and Jeff, shouting and sharing. It’s like the life of the shtetl described by Cuddihy, passed down through the generations and built into the culture.

For many Jewish photographers of the 20th century, such as Robert Frank and Nan Goldin, intimacy has been key to their work. They show us that we learn more about human nature when we move past the fake smiles and best selves. There is respect and dignity in Roman Vishniac’s photographs, he is not like Bruce Gilden or Diane Arbus, but the desire to see things truthfully, and with emotional attachment, is strong.

To learn more about his fascinating life, check out the recent film, Vishniac (2023).

New reader here! The photographs are stunning and you give much food for thought and further learning. Thank you 🙏

Another great photographer I foolishly knew nothing about, thank you for new knowledge!