Guess how much Friedrich Nietzsche wrote about photography in his published works? A couple of aphorisms? A footnote? A casual aside?

The correct answer, as far as I have been able to discover, is nothing.1 Nietzsche, despite being around at the birth of a dazzling technical innovation, was indifferent to it as a topic.

I expected to find something in his corpus because his writings are so diffuse and wide-ranging, but Nietzsche was a psychologist and a moralist who was rarely distracted by contemporary events.

While Nietzsche didn't care about photography, photography cared about him. He is one of the first great thinkers of whom there are a decent set of photos. What do these images add to our understanding of him and his ideas?

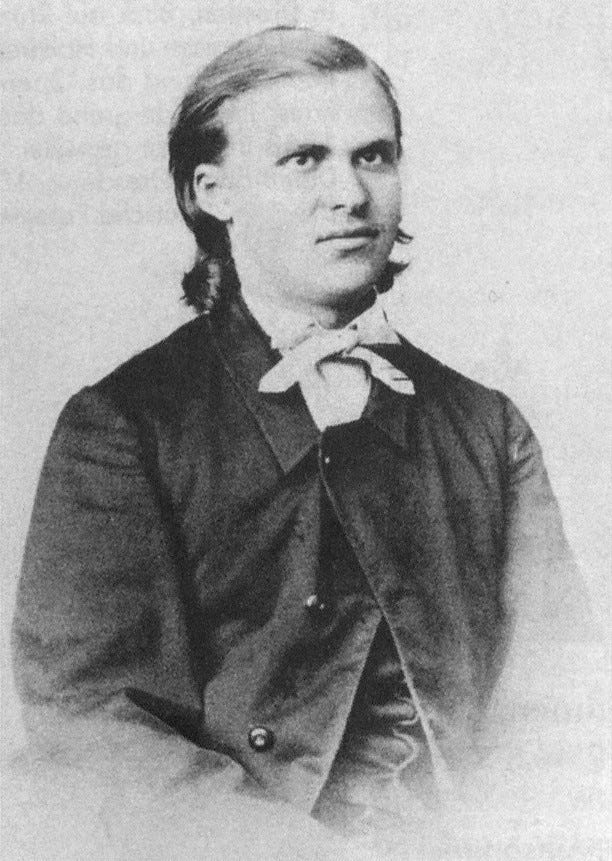

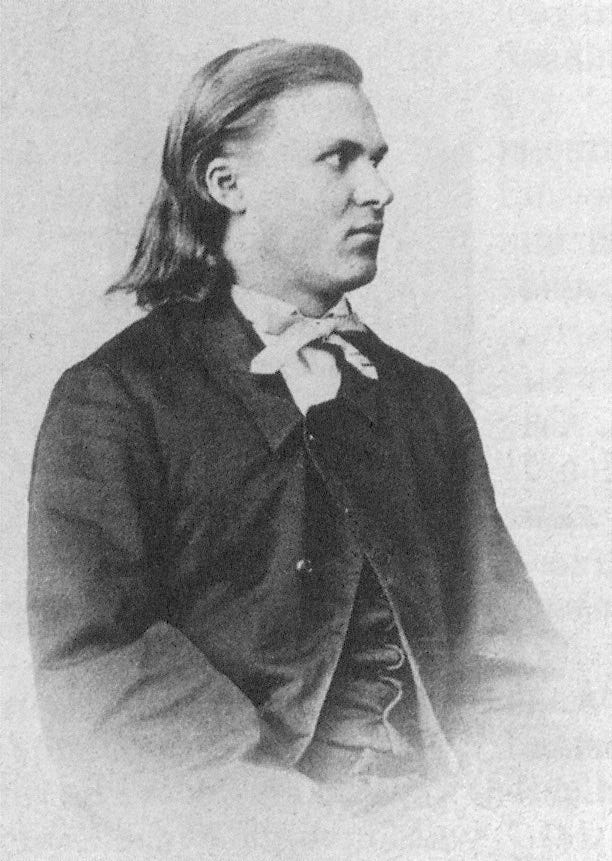

1861

The earliest photograph we have of Nietzsche is from 18612, which is early for a photograph. The daguerreotype was patented in 1839 and the collodion process used by Lewis Carroll only superseded it in 1851. The technology was exciting and becoming widely available. In 1851, Augustus Washington was advertising prices ranging from 50 cents to $10 (between $20-$400 in today’s money).

Daniel Blue, an independent scholar and author of The Making of Friedrich Nietzsche: The Quest for Identity, 1844-1869, quotes Nietzsche writing to his mother: “My stance is hunched, my feet somewhat crooked, and my hand looks like a dumpling.”

A portrait makes you acutely aware of how you might come across to others. Whilst the teenager can stare at themselves in the mirror, there is an objectivity to a photograph that undermines the self-image we think we are projecting.3

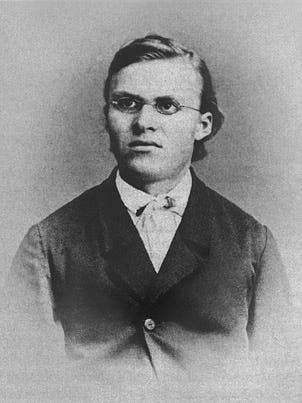

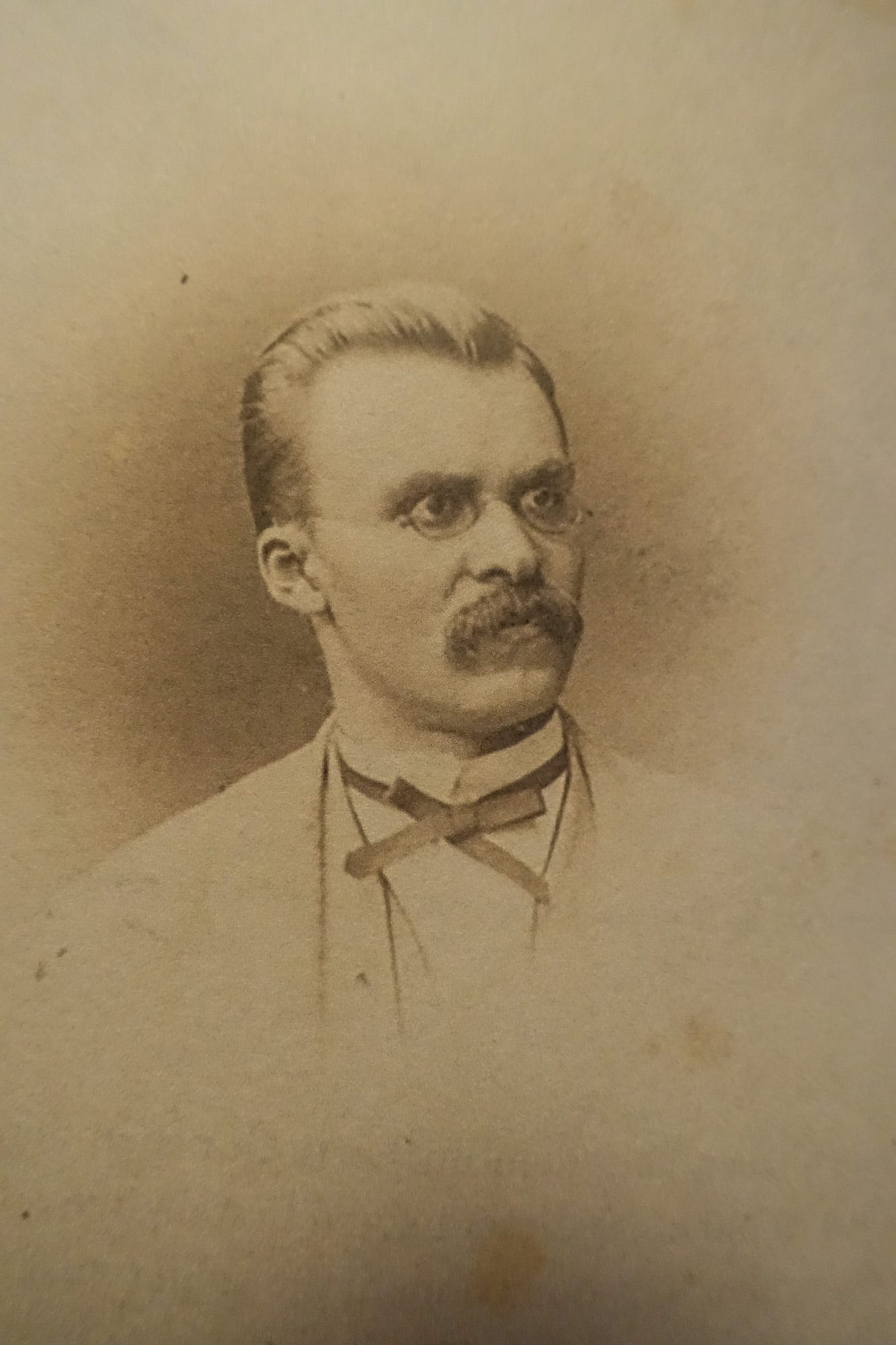

1862

Nietzsche in 1862 has the recognisable look of the arrogant seventeen year old. A friend on Twitter said he was reminded of Manchester City’s blond beast übermensch, Erling Haaland.

Daniel Blue writes: “Nietzsche himself seems to have regarded these photos as unfortunate, but he gave copies to Franziska, Elisabeth, and Rosalie and reserved three others for friends at Pforta. Gustav [Krug] […] had come to recognize in Nietzsche a dangerous superior, to be placated, flattered, and feared.”

Throughout his life, Nietzsche suffered health problems including debilitating headaches. History has come to see him as a sickly man who inverted his sickness into vitalist philosophy, but he looks pretty healthy and Byronic here.

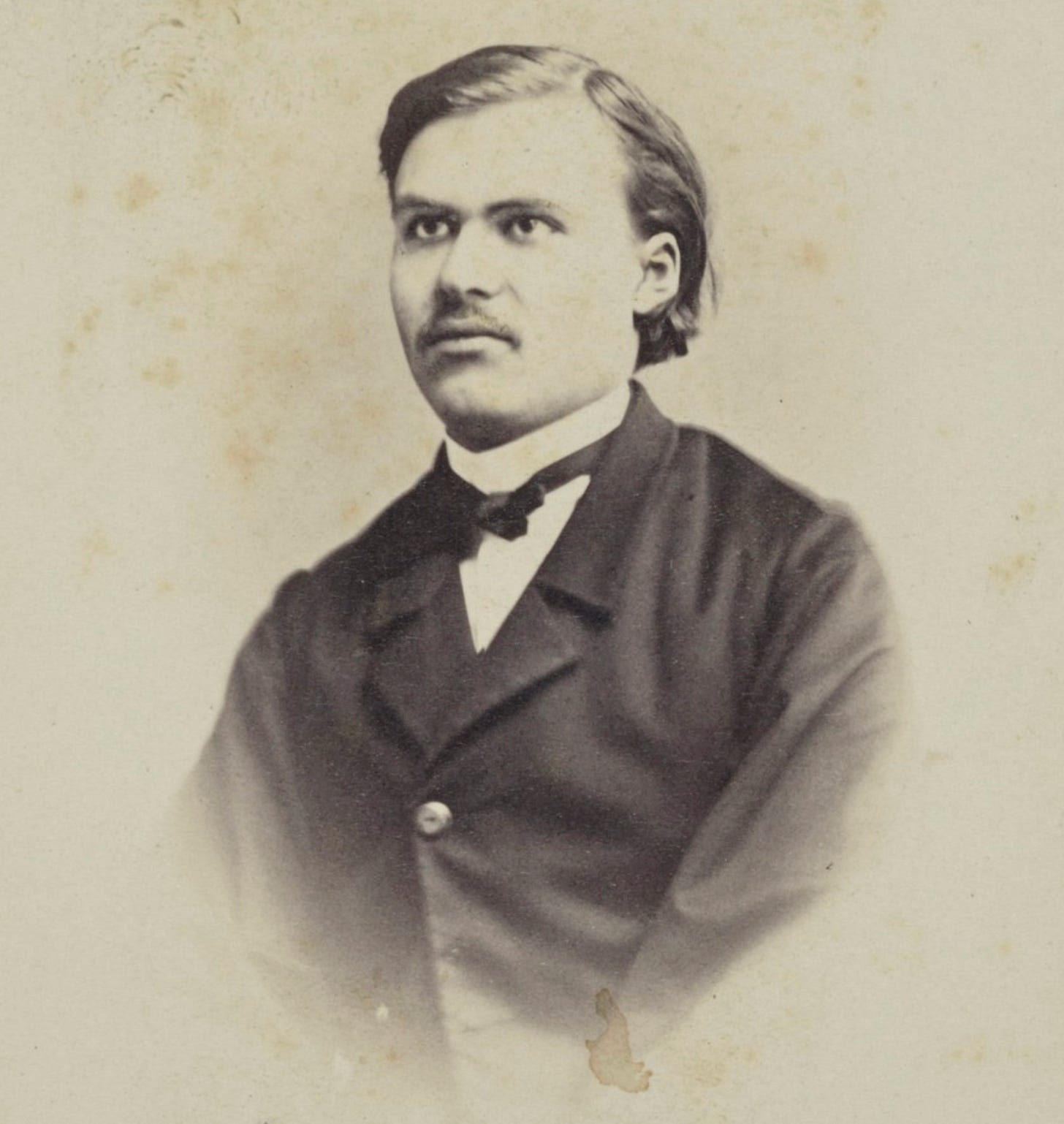

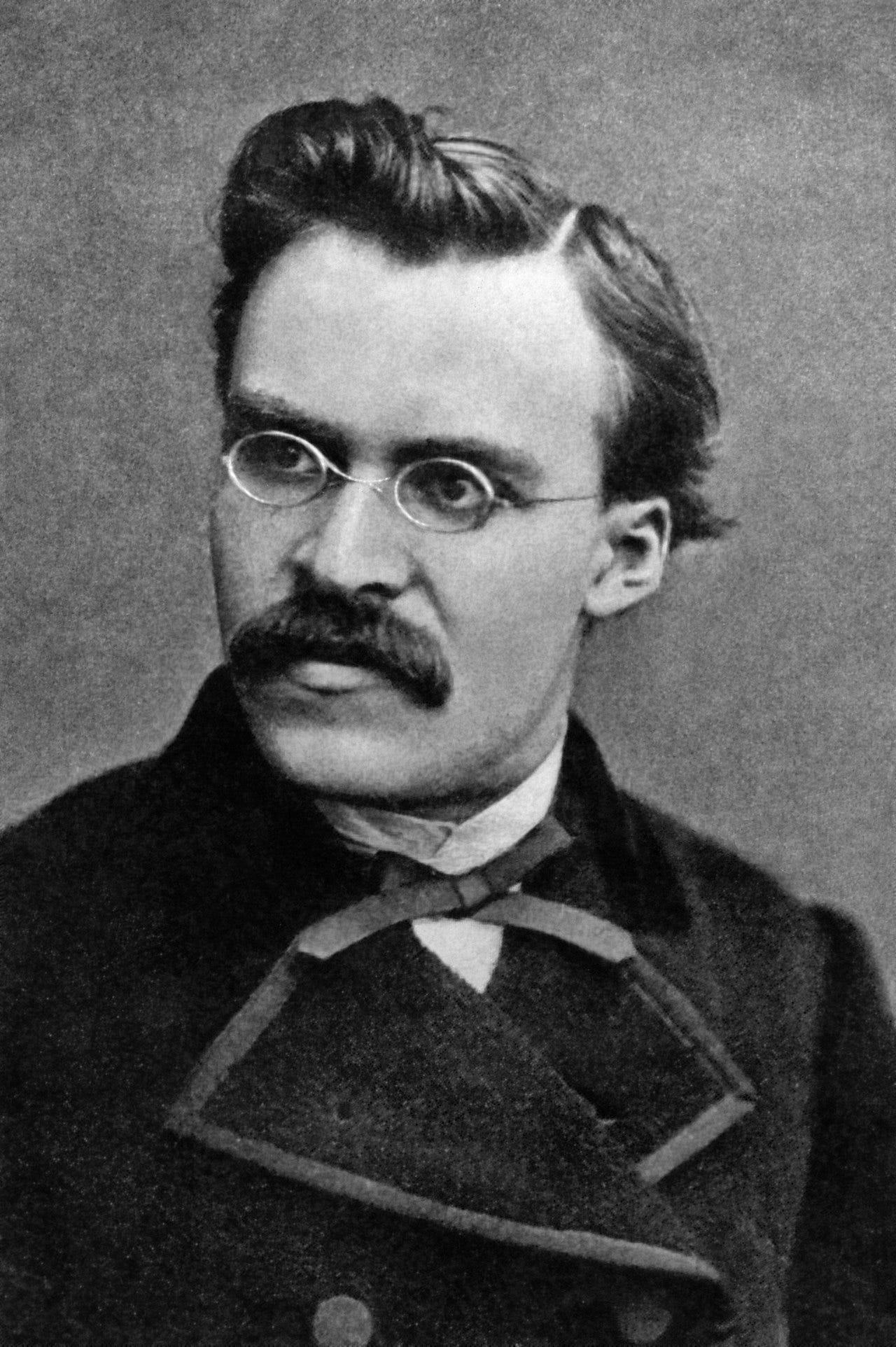

1864

In 1864, aged 19/20, the scholar emerges. He has added seriousness to the arrogance, looking very much like the son of a Lutheran pastor. Those small, studious glasses cannot dim the intensity of his visionary gaze.

I used to think that the moustache is the worst of both facial hair worlds—a beard doesn’t take much maintenance and a clean face is consistent—but the awkwardness of the upper lip with the philtrum groove can be very annoying to shave.

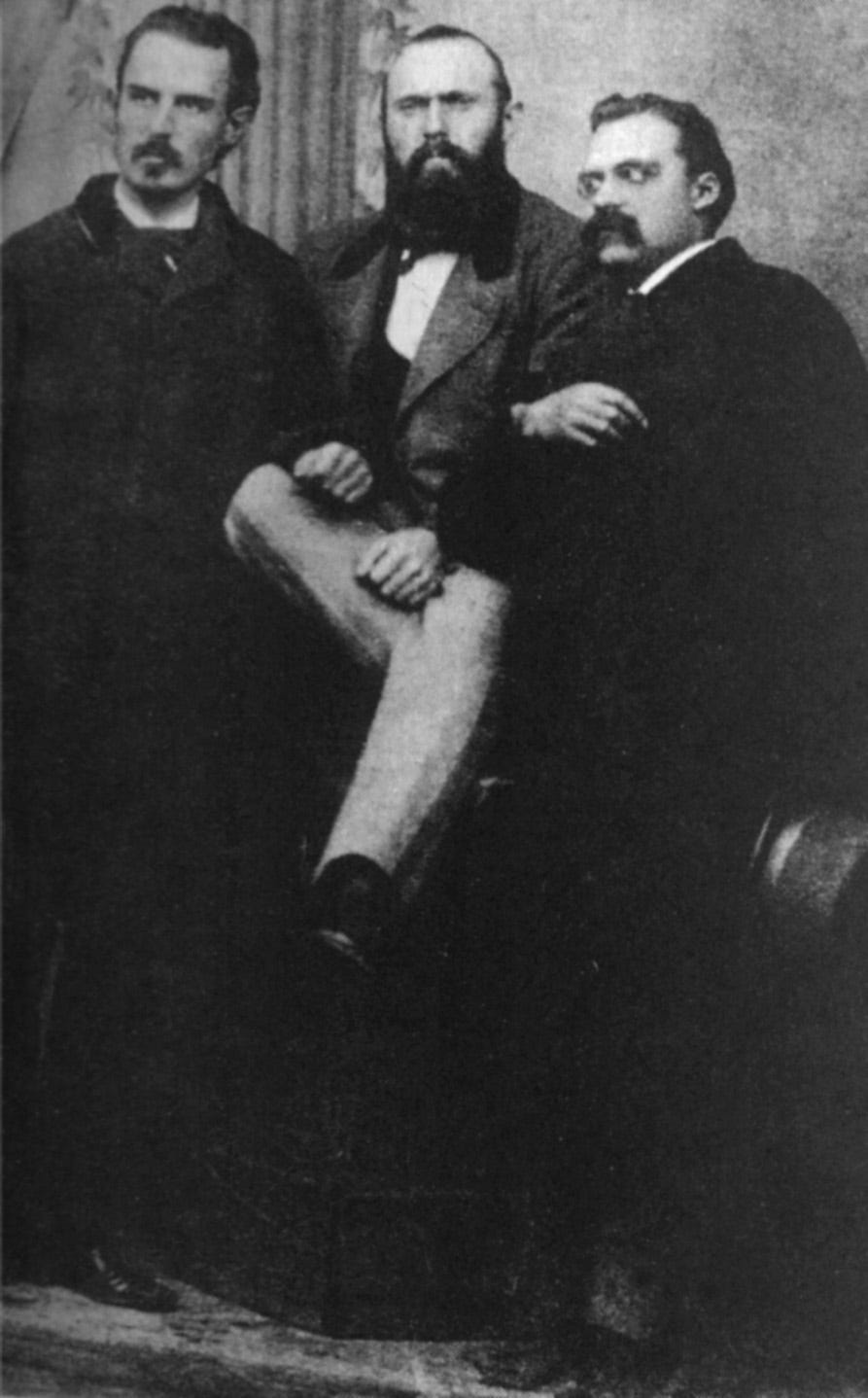

1866

Nietzsche, with his contemporaries from the student philological organization in Leipzig. He is not difficult to spot: his big domed head, his thick moustache, and the fact that he is looking in the other direction all make him stand out amongst his milquetoast associates.

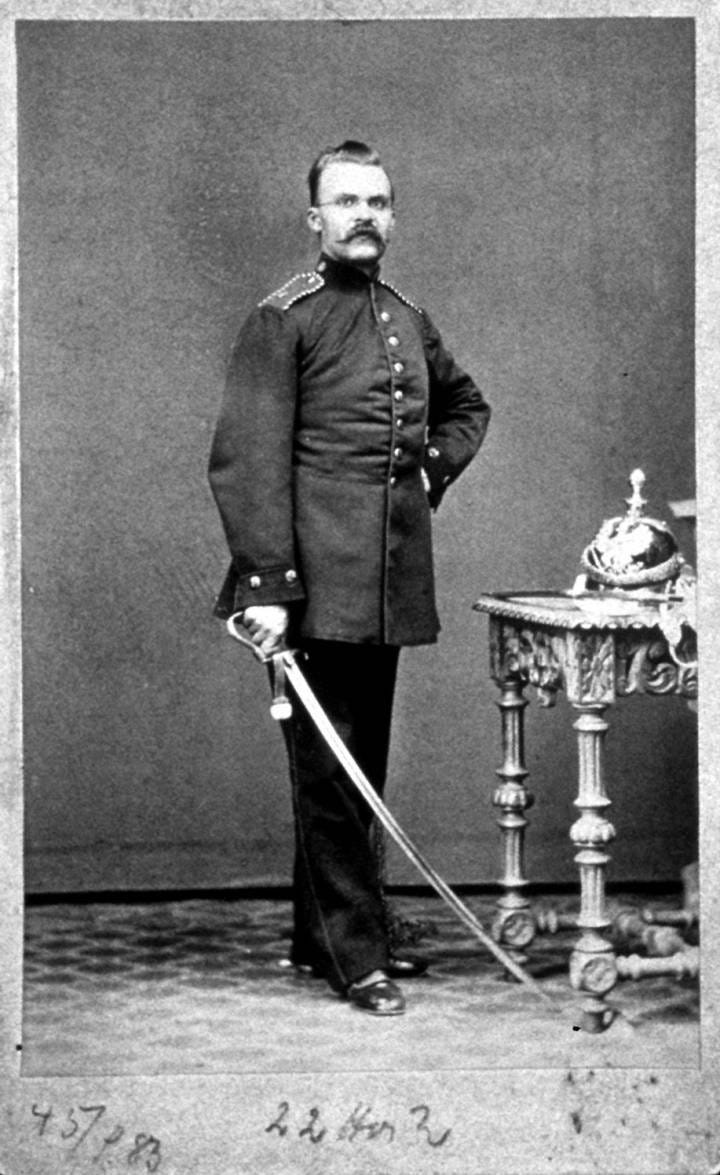

1868

Nietzsche did not have a distinguished service record during his time in the Army. Again, from Blue’s book:

“My career as warrior has not set the stage on fire,” he conceded […] Aside from the damage to his chest, this picture would be his sole memento from his arduous year in the army. It is regrettable, then, that it turned out to be unflattering, a judgment Nietzsche himself implicitly rendered when he tried to explain to Rohde what had gone wrong. It showed him, he admitted, in a somewhat aggressive pose, accosting his friend rudely with drawn saber and with “an irritable and unpleasant” expression on his face. “But why does the miserable photographer annoy us . . . ? Why must we always be ready with our sword? And when we’re about to rush precipitously upon [him], what does he do? He ducks under his mantle and shouts, ‘Freeze!’”

It sounds like the photographer had his own sense of Nietzsche’s character and prodded him until he got the expression he wanted. As Anna Khachiyan says:

"The best way to find out what someone thinks of you is how they take a picture of you. Because it’s how they see you."

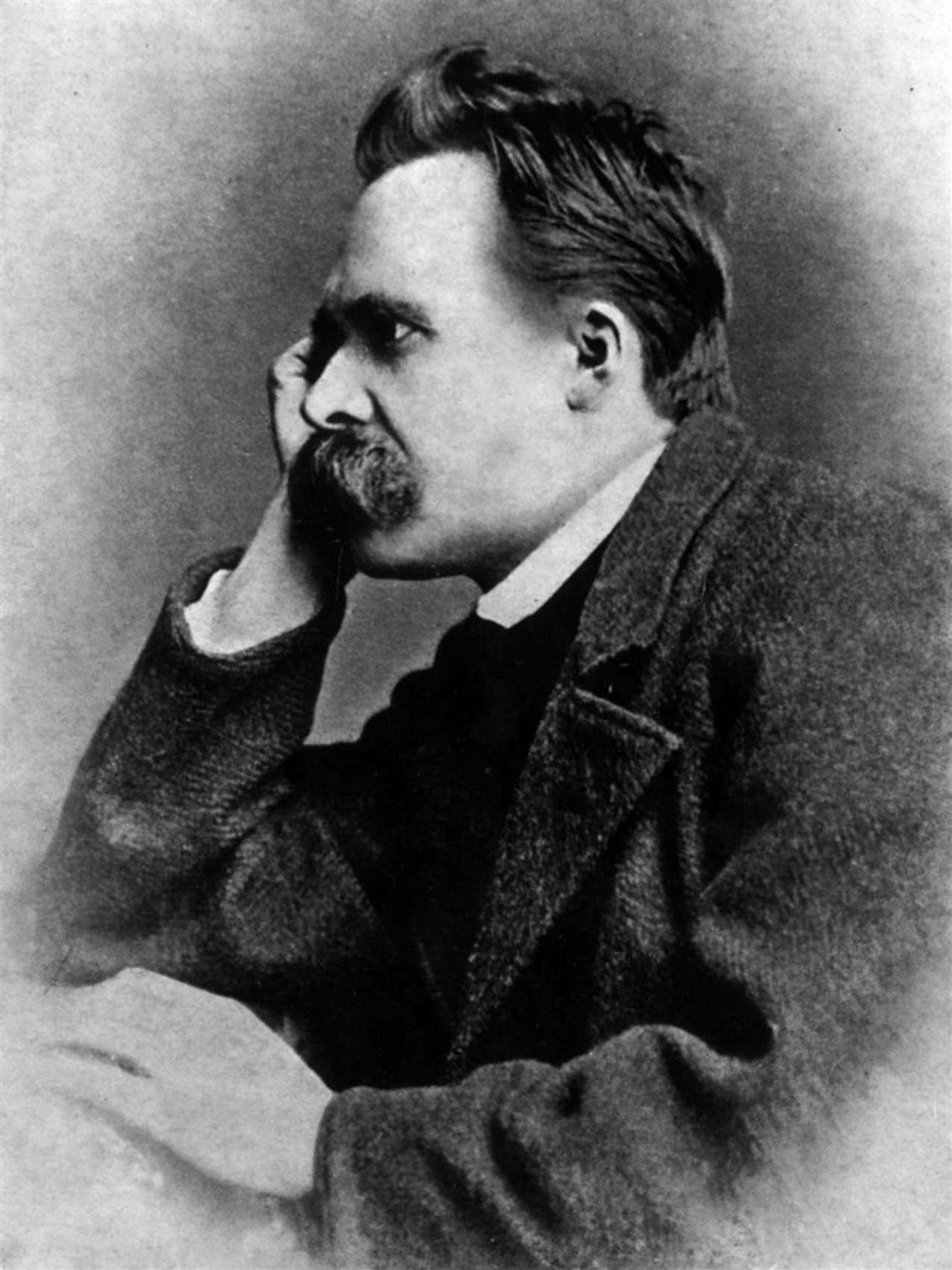

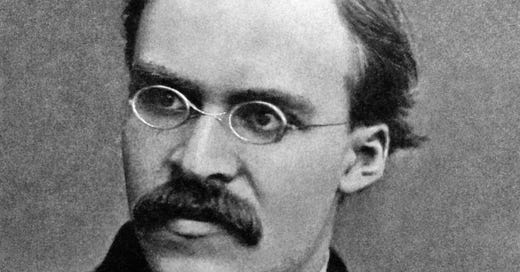

1869

After all these photographic failures, this one captures the Nietzsche we know from the books: the caustic wit and savage certainty. It is used on the cover of Paul Strathern’s introduction to his thought, amongst other books.

1871

This photograph is from a vacation in Lugano in 1871, when he is 26 years old, makes him look very much like a man of his time. It feels modern to see him staring at the camera, impatient for it to be over.

“He who cannot obey himself will be commanded.”

A letter from Nietzsche to Erwin Rohde, Lugano, Hotel du Parc, March 29, 1871:

Ah, how I long for good health! One has only to plan something that will last longer than oneself -- then one is thankful for every good night spent, for every warm ray of sun, even for an orderly digestive system! But with me certain abdominal organs are disturbed. Hence nerves and sleeplessness, hemorrhoids and the taste of blood, and so on. Kindly do not ascribe the condition of mind described above to the condition of my ganglia too! Or I might fear for my immortality, for I have never heard of flatulence inspiring a philosophical state.

1872

Nietzsche was an academic prodigy and became the youngest full Professor of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in Switzerland. The dandiacal moustache reflects his confidence and the confidence of the German Empire under Wilhelm I and Bismarck.

1873

Let us now picture the abstract man, untutored by myth; abstract education; abstract morality; abstract law; abstract state; let us imagine the lawless roving of the artistic imagination, unchecked by any native myth; let us think of a culture that has no fixed and sacred primordial site but is doomed to exhaust all possibilities and to nourish itself wretchedly on all other cultures—there we have the present age, the result of that Socratism which is bent on the destruction of myth.

1875

Instruction from pictures. If we consider a series of pictures of ourselves from the time of childhood to that of manhood, we are agreeably surprised to find that the man resembles the child more than the adolescent: probably corresponding to this occurrence, then, there has been a temporary alienation from our basic character, now overcome again by the man's collected, concentrated strength. This perception agrees with the one that all those strong influences of our passions, our teachers, or political events, which pull us about in our adolescence, later seem to be reduced to a fixed measure. Certainly, they continue to live and act in us, but our basic feeling and basic thinking have the upper hand; these influences are used as sources of power, but no longer as regulators, as happens in our twenties. Thus man's thinking and feeling appear again more in accord with that of his childhood years-and this inner fact is expressed in the external one mentioned above.

From Human, All-Too-Human (1878-80)

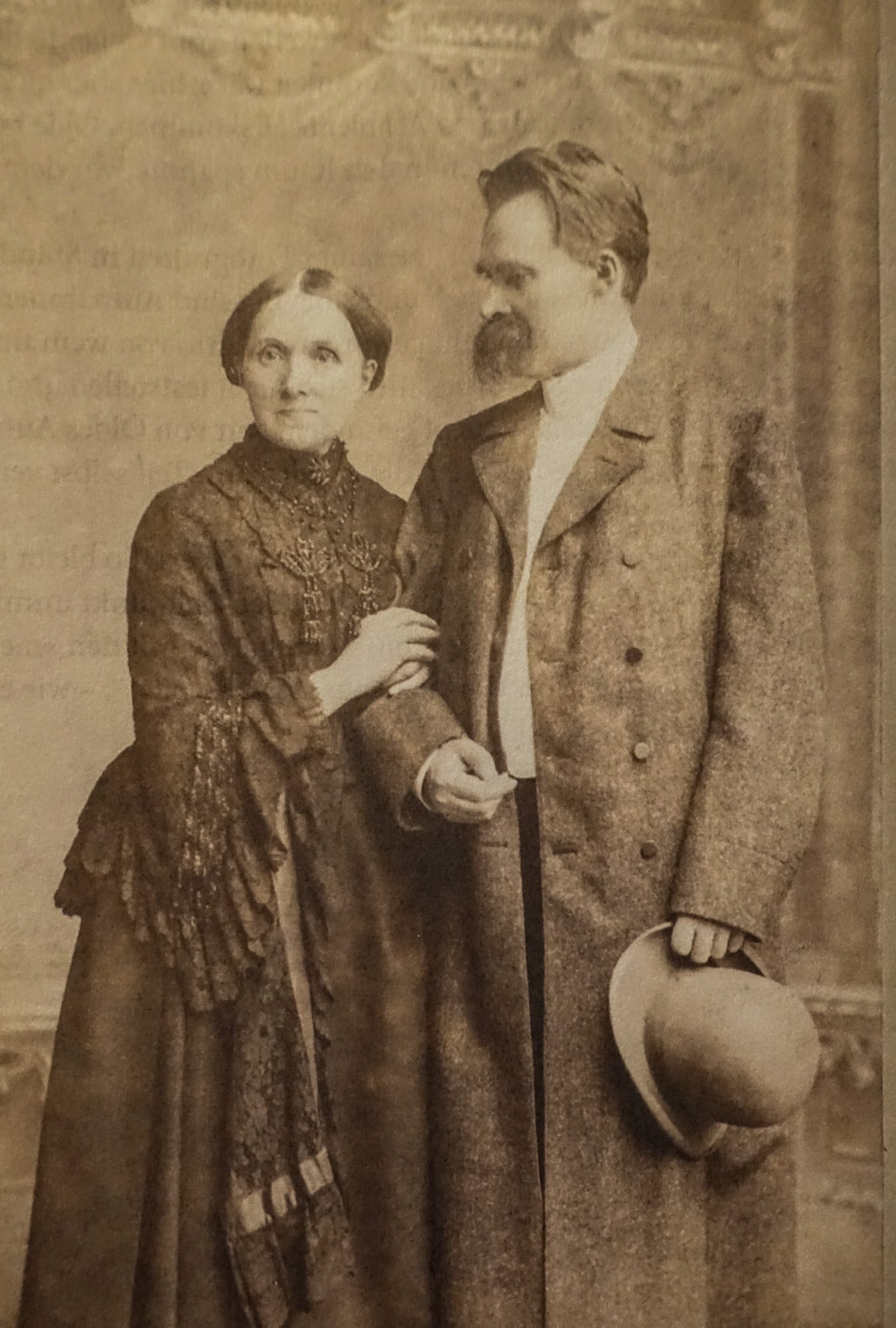

1882

Nietzsche’s famous line “Are you going to the women? Don’t forget the whip!” is often interpreted as meaning that you should bring something to control women. But from the context, it is clear that he is talking about the whip they carry, not the whip you bring. This posed photo with Lou Salomé and Paul Reé makes it even more obvious that this is the meaning.

It was after looking at this picture that I was curious about what Nietzsche writes about photography. We now think that photography changed how we see the world, surely in his voluminous archives there is some reference to this technology? Well, no, but in Human, All-Too-Human (1878-80) there is this line:

The printing press, the machine, the railway, the telegraph are premises whose thousand-year conclusions no one has yet had the courage to draw

1882

Nietzsche is the quintessential philosophers of modernity, a visionary reactionary who rejected democracy and foresaw the terrors of the 20th century. One of the reasons that Nietzsche is still read is that he doesn't get bogged down in the details of the day. He may mention English utilitarians in passing, but not the individuals by name.

These photos of Nietzsche in 1882, shortly before Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883) was published, capture him at the height of his self-mythologising. There would be more books, increasingly frenetic and willful, but no more photographs, at least not that he chose to have taken.

I am fascinated by the way in which the perception of great thinkers is shaped by the images we have of them and the images that get chosen by publishers to adorn the books. How would Nietzsche be understood differently if we only had a picture of him from 1864, the son of a Lutheran pastor, rather than the stern thinker below?

One of the reasons I was curious about Nietzsche and photography is because he was an early adopter. In 1882, he started using an early typewriter, the Hansen Writing Ball.

On February 16, 1882 he even wrote a poem about his writing ball:

THE WRITING BALL IS A THING LIKE ME:

MADE OF IRON YET EASILY TWISTED ON JOURNEYS.

PATIENCE AND TACT ARE REQUIRED IN ABUNDANCE

AS WELL AS FINE FINGERS TO USE US.”

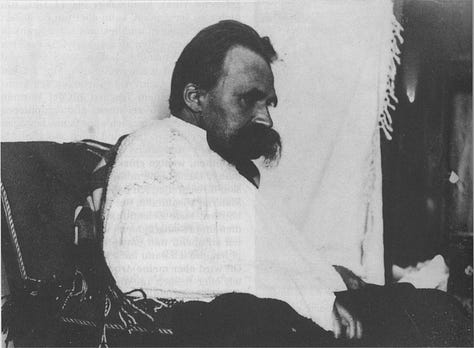

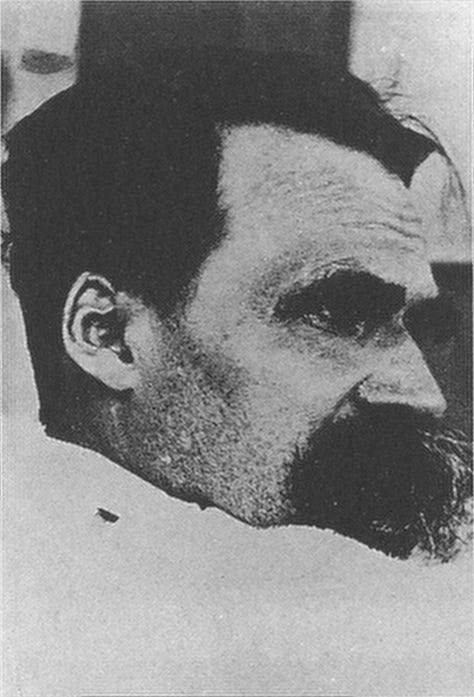

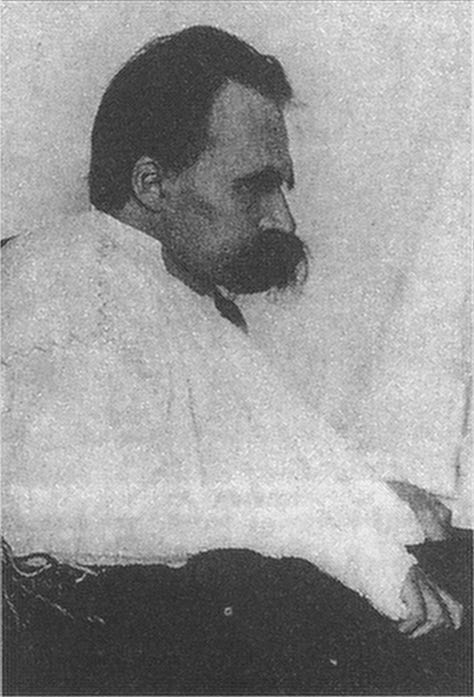

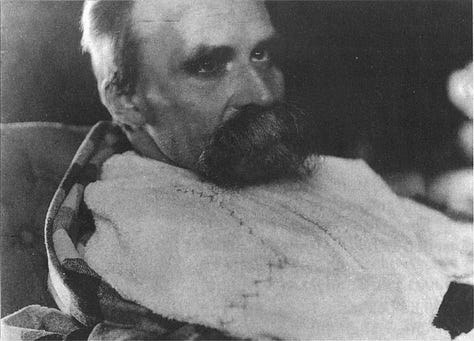

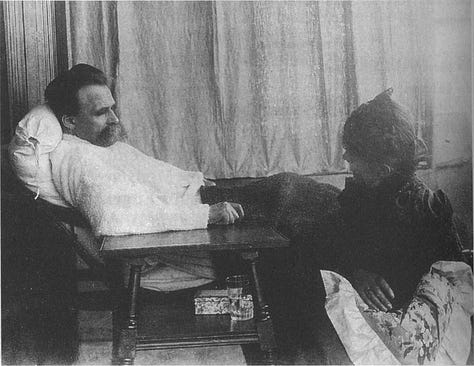

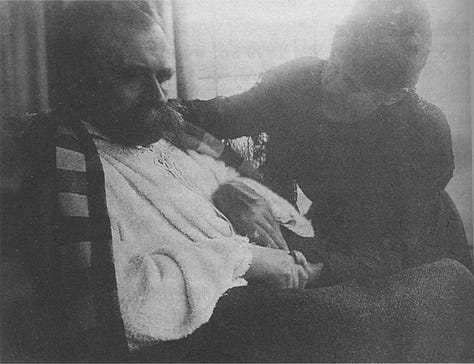

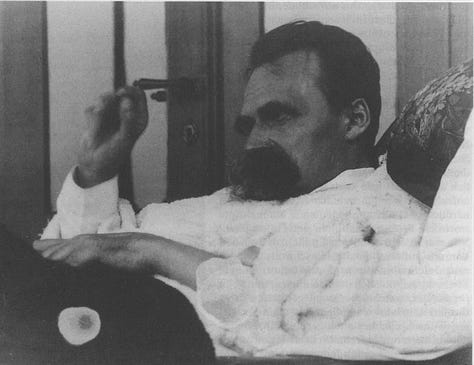

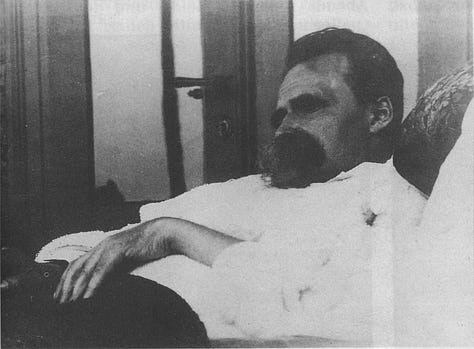

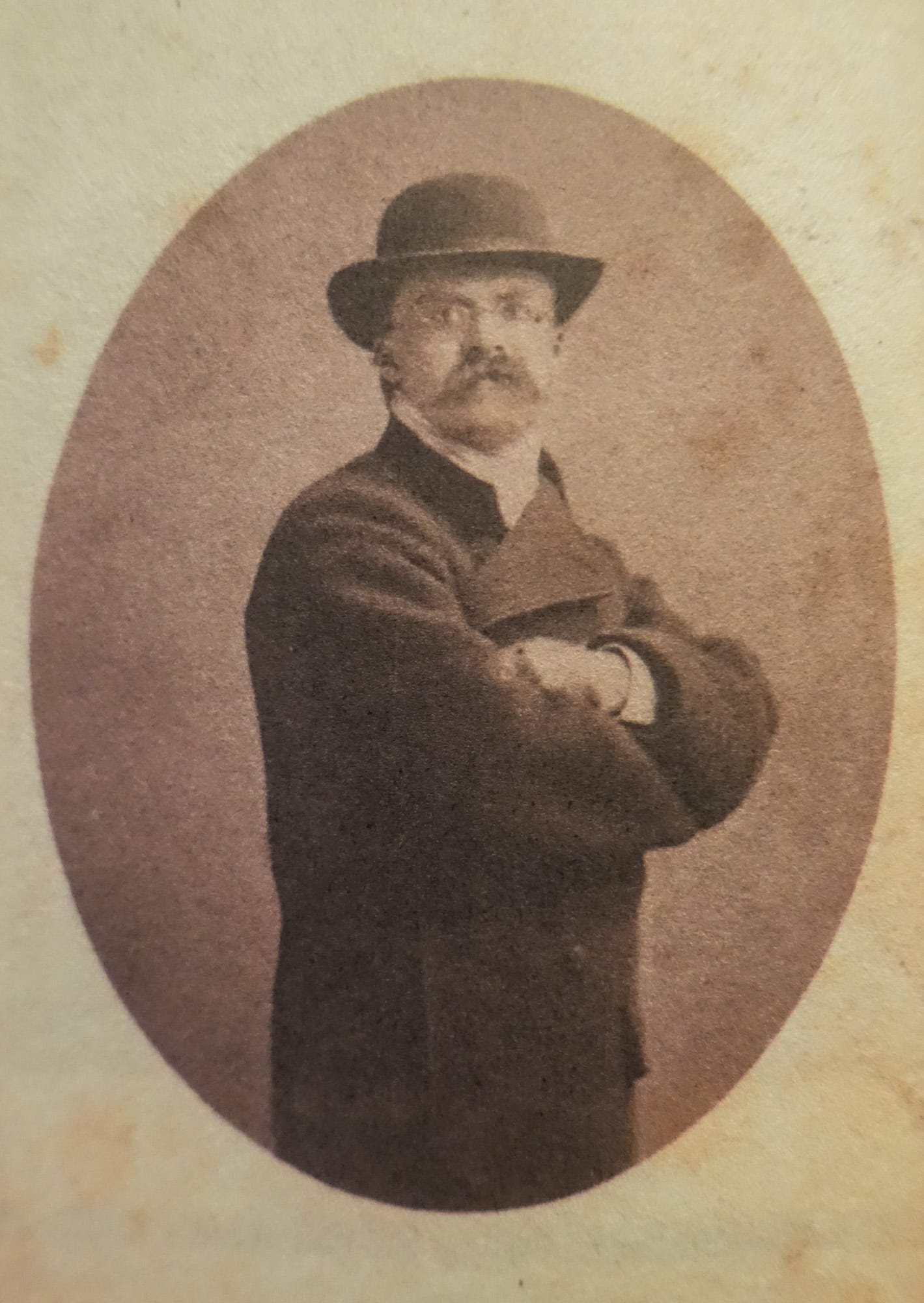

1892

On 3 January 1889, Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown and lived for the rest of his life with his mother and sister.

It being 2023, I couldn’t help but ask ChatGPT what Nietzsche might have said about photography:

In regards to photography, Nietzsche might have seen it as a representation of reality that lacked the imaginative and expressive qualities of traditional art forms such as painting and sculpture. He may have viewed the mechanical nature of photography as a barrier to the creation of truly great art, and saw it as limited in its ability to convey deeper truths and evoke strong emotions in the viewer.

However, it's also possible that Nietzsche would have recognized photography as a new art form with its own unique qualities and possibilities for expression. He may have seen the potential for photographers to use their medium to create powerful and meaningful images that go beyond mere representation.

Maybe Bing’s Sydney would be less reasonable.

1894

Hello History is an AI chatbot that purports to allow you to chat with historical figures. It is not very good. I asked its version of Nietzsche about photography:

1899

It’s sad to see Nietzsche in his final ten years—post-breakdown, aphasic, barely there at all—but these images helped establish him as a man of his age: an existentialist! Someone who had stared down into the abyss and couldn’t recover.

Update (15 April 2025)

Someone I encountered on the Nietzsche Reddit board has examined Nietzsche’s letters, many untranslated, and compiled a more complete list of references to photography. Read more at Intempestive Meditations.

For this claim, I did a keyword search on the 1909 translation of the complete works, plus an online archive and a quick Google. The closest I found to a comment on photography is in his letters. On The Nietzsche Channel, a site that translates letters and unearths fragments, they quote a letter to Jenny Rée where he writes (Leipzig, ca. September 16, 1882): "Look at this picture and don't be startled: that's me."

There is a reproduction of this photo that suggests it is from the studio of the pioneering German photographer, Louis Held, but the timelines don't quite match up with Held's own career, so this is likely a reprint. Held did take photos of Nietzsche's sister, Elisabeth Forster-Nietzsche, so it is possible that they collected together archival materials to help shape the myth.

Here is the full passage from Blue’s book:

This is the first extant full portrait of Nietzsche and probably the first that he had ever seen; and for a self-conscious adolescent the effigy must have given rise to reflections, even if the picture was unflattering. Feet apart and leaning against a plinth, with right hand thrust inside his coat like Napoleon, he resembled countless adolescents caught transfixed in the ceremony of the yearbook photo. Nietzsche acknowledged the picture’s homelier aspects in a letter to his mother and sister: “My stance is hunched, my feet somewhat crooked, and my hand looks like a dumpling.” Despite such misgivings, he seemed more pleased than chagrinned and asked specifically who would receive a copy.

The more you (figuratively 'you') learn about Nietzsche, the more of a tragic and individual figure he becomes. The two primary 'schools' around him, that being the stereotypes of nihilistic teenagers and National Socialists, have done him a severe disservice.

Excellent.