The Detonating Presence of Peter Hujar

An interview with John Douglas Millar, co-curator of Peter Hujar — Eyes Open in the Dark and Peter Hujar's biographer.

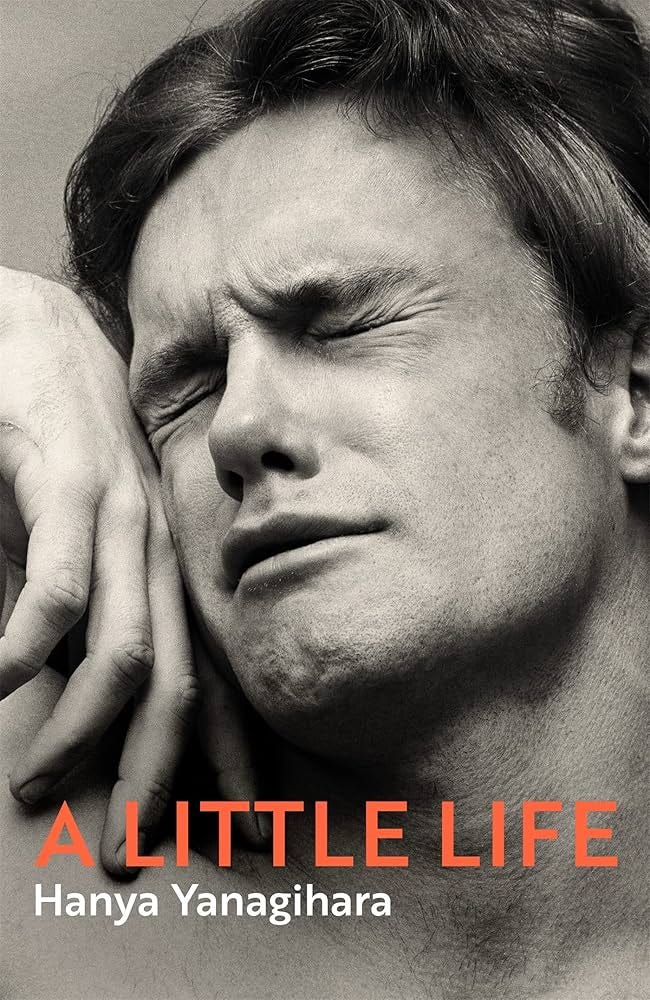

I first became aware of Peter Hujar after seeing the cover of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life. Every bestseller table of every bookshop seemed to feature that striking image of an anguished man writhing in pain.

Embarrassingly, I went months assuming it was a nineteenth-century photograph of Lewis Powell, one of the men behind Lincoln’s assassination. But it wasn’t. The man wasn’t even in pain. When I finally inspected the back of the book, I was startled to see it credited as Orgasmic Man (1969) by Peter Hujar.

Both the title and my mistake made the photographer more intriguing. I started seeing Hujar everywhere. I went to a talk with Andrew Durbin, editor of Frieze, who mentioned he was writing a book about the relationship between Hujar and Paul Thek. Hip gallery gift shops proudly displayed the compilation of the visual journal, Newspaper, which Hujar co-edited. So, when in 2023 Nan Goldin was named the most influential person in the art world, it made sense to me that other figures from the era would come to be celebrated.

Yet all this was background noise until I heard that John Douglas Millar, someone I knew as a literary critic, was co-curating an exhibition of his work at Raven Row in London. Finally, I had a chance to see it up close.

Without resorting to hyperbole, it was one of the best exhibitions I’ve ever seen. Hujar’s photographs have a sublime stillness, they evoke a devastating sense of presence. The quality and consistency of the prints allow the viewer to flow from one image to the next, without being interrupted by questions of form. His photographs show life made visible by the presence of death: sex and death, friendship and death, love and death, awareness and death. As his friend Susan Sontag wrote in her diary in 1976: “Death is the opposite of everything.”

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about the absence of aura in the digital reproductions of Maud Sulter’s photographs. That exhibition looked good on the phone but was totally flat in person. With Hujar, I had the opposite problem. Every time I tried to take a photo of a Hujar print, it was like a shadow of the real thing. The thing on the wall was alive … the sense of presence, stillness, the tonal range. There was magic in these photographs.

Inspired by this ecstatic encounter, I got in touch with the co-curator, John Douglas Millar, who kindly agreed to speak to me about Hujar and the exhibition.

Interview with John Douglas Millar

Neil Scott: I looked in my diary and apparently it's almost nine years since I saw you at the book launch for Brutalist Readings.

John Douglas Millar: Oh God, you were there! It's a book I have a certain amount of ambivalence about these days.

I was wondering if you could tell us about the path that led you from there to Peter Hujar?

I first saw Peter Hujar's work around 2003. I had a friend who was a photographer studying at Duncan of Jordanstone. He had taken the Grey catalogue out of the library and was showing me the pictures. I thought they were completely remarkable, I hadn’t seen images that were affecting in that way before, and not only the human portraits, I thought the animal images were unbelievably powerful. They were a question and I didn’t have an answer. A year or two later the famous Candy Darling image appeared on the Antony and the Johnsons’ record ‘I Am a Bird Now.’

I then got sidetracked by other things, including Brutalist Readings, writing about conceptualism and starting a PhD on the poet Paul Celan; things that are seemingly quite far from Hujar's orbit. Then, around 2018, my father got very ill with bowel cancer and was in hospital for a long time, for weeks and weeks, and eventually died. Five months later, my son was born and then, a year after that, COVID happened.

When we were in lockdown, I bought the 2018 Morgan Library catalogue and that book became a way of thinking through grief because Hujar is so interested in bodies in transit states, whether that's orgasm or death or birth or whatever. His approach to the body, to the sitter, and to human frailty helped me think through and inhabit those experiences—helped me actually to feel them. So it was quite personal in that respect.

You’ve co-curated this exhibition and are currently writing a biography of Hujar, I am curious about the extent to which the exhibition is a way of shining a light on his life in a particular way.

Absolutely. The top floor of the exhibition is all about 1976. The room that contains the contact sheets and the images from Easter Sunday, those two rooms and the David Wojnarowicz Sex Series piece. That is basically the first chapter of the book. You can follow Hujar around Manhattan on Easter Sunday 1976. He begins uptown shooting the faithful on the steps of Saint Patrick’s on 50th and 5th. Then moves down to the West Side piers where he shoots this very ebullient queer scene, and then at the end of the day he ascends the World Trade Center and takes a photo that scans across the East River, catches the edge of the Lower East Side and the cruising grounds around the decommissioned naval docks in Brooklyn. It’s a remarkable day. And in those contact sheets you can see Marsha P Johnston, Stephen Varble, Camille O’Grady and others. It’s very rich, inherently novelistic really.

Downstairs is much more of an associative hang that was done in situ. Gary Schneider [the other co-curator] and I worked for two years on which images were going to go into the show, so we really had a feel for these particular images before installing them.

It was fascinating to see the contact sheets from Easter Sunday because apparently there is a film coming out called Peter Hujar's Day. I don't know if you've already seen that or if you've been involved ...

No, I have nothing to do with it and haven't seen it. I want to see it, but there's no connection.

It's based on a transcript of an interview … maybe one day people turn this interview into a feature film.

[Laughs]

After I saw the exhibition, I went back to your social media and it says your Hujar biography is not due until 2029. I thought: "2029! This is going to be an epic undertaking."

I think that's partly why when the possibility came up of doing the book, I accepted. I realized that I was going to be working on Hujar for a very long time anyway, so it might as well become my life entirely, which it is now. It's a fascinating process.

My friend Tom Overton has just finished John Berger's biography for Penguin. He said to me there are two key points in writing a biography. The first is where you realize that you know more about the person than they knew themselves, and the second is the point at which you start to dislike the person. Happily, that hasn't happened to me yet, though my image of him has become more and more complex, he was a very layered and fascinating human being.

There are so many stories being told about this period. The editor of Frieze, Andrew Durbin, is writing a book about Paul Thek and Peter Hujar. There's the recent Nan Goldin and Fran Lebowitz films. David Johansson died the other day. Even in the recent film, The Apprentice, Trump is there hanging out with Andy Warhol. There was so much going on in New York at that time. I'm curious about how you are going to contain all of these stories within this epic life?

What’s interesting to me is trying to write something like a materialist account of that period because it has become pure mythography to some degree. How do you contain all those stories?

Well, with Peter Hujar there isn't a huge material record of his life. He didn't leave diaries. There's one or two interviews. He kept letters sent to him, but very few of his letters to others exist. There's a point where you have to accept that this will largely be an oral history and try to turn that into a positive rather than a negative. Any biography is about present absence, but it's even more interesting when the person you're writing about is a photographer and their photography is about present absence. Reflecting that in the book is part of the formal challenge of writing it.

One of the aims for the show was to show Peter as an artist and not as part of some mythographised East Village scene. It was to take the work as seriously as possible and also to take the relationships as seriously as possible. I'm trying to do the same thing with the book and not make it another story about Studio 54 or whatever. That doesn't particularly interest me. It's a misnomer anyway, because in lots of ways Hujar was a fifties and sixties artist who happened to be a mentor to some of those people in the seventies and eighties, but I don't think that's really where his art is situated.

One of the things about writing his biography is you quickly realize how shallow the narratives of art history in New York are that we are commonly fed. Once you start to look at the anthropology and the sociology of the period—who was connected to who and who was working with who—the period becomes more interesting and less fixed. Peter was photographing Annette Michelson, Susan Sontag and Yvonne Rainer as well as Cookie Mueller and John Heys, he was photographing people from both a more uptown patrician culture and downtown art-making and those scenes or fields come together in really interesting ways that are not always accounted for.

It’s true, though, that most of the photographs in the show are from the seventies and eighties. In the catalogue, you write about all things that are outside of the frame. For instance, I hadn't realized all these kinds of crazy spiritual journeys that he went on in the Sixties. How do you think his spirituality changed the photographs? I’m thinking particularly about the sense of animism in the work.

It’s true that there is this sense of animism in the work. There's a quote in David Wojnarowicz’ Close to the Knives, where he's talking about Hujar's dying and they've been looking for some quack doctor who has been injecting patients with typhoid, the idea being that it will get their immune systems to jumpstart. It's been the most awful day and on the way back they stop at a burger joint and Wojnarowicz describes how miserable it is: it's just the freeway going past outside and flapping motorway signs and pylons and whatever. And Hujar looks up and says, “America is a beautiful country, don't you think so?” Wojnarowicz says “We were so tired and exhausted and the day was so awful that I just wanted to go home and not have to think about it.” And then Hujar says "You wouldn't understand what I mean anyway."

It's interesting to think about what he actually meant by that because that speaks to the animism—this sort of Whitmanian sense to Hujar's work. Gary Schneider said something to me when we were installing, which is that people talk about the melancholy of the images all the time, but the truth is they're celebratory. Hujar's work is a celebration. It contains darkness because life contains darkness, but it's a celebration. I think that’s true. Hujar almost exclusively used the same square format for his prints, and I think too that that speaks to this Whitmanian element, each thing deserves the same attention—a horse, a tree, a human—and the images invite us to consider what our responsibility is to the thing represented, how do we care for them, whatever their nature? They posit that responsibility of attention and care. That feels very significant right now.

One of the narratives about Hujar is that he had a deep depression, quit working for a commercial photographer, and then re-emerged in 1976 with the late flourishing that features in your show.

He definitely went through a period of depression in the mid-seventies. He was prone to depression all through his life. It wasn’t only this one moment when he really was struggling in the mid-seventies. He'd made this decision to go his own way with his work, but he'd been struggling for money for so long and he just got to the point where the struggle had become too much.

Then his friend, the choreographer James Waring's death from cancer at the end of 1975, really affected him. He’d been caring for him in his last months and finishing Portraits in Life and Death at the same time. I think he was just exhausted. In 1976, he seems to have processed things and he comes out of that with a new energy which is represented in the upper floor of the exhibition at Raven Row.

In Adrian Rifkin’s text in the catalogue, there's an implication that Hujar did a masterclass with Michaelangelo Antonioni. I don't know if that’s a myth, but it's interesting looking at the photographs through an Antonionian lens. Who are the other big influences? I know he studied under Richard Avedon and was inspired by Weegee’s night photos.

Berenice Abbott is another, Lisette Model, Irving Penn, August Sander, Julia Margaret Cameron. I don’t know if he knew Antonioni but he was studying film at Cinecittà in the early 60s. He was certainly moving in circles close to Fellini. Rome was quite small at the time, though culturally very vibrant. There was an expat crowd around Richard Weaver who was translating Pasolini at that time and who was friends with Hujar’s old schoolteacher and mentor figure Daisy Aldan. It's a really fascinating part of his life.

When I first saw the self-portrait from 1958, I assumed it was a typo. It doesn’t look alien to anything else he did at the time.

There's the gesture. The gesture is pure Brando. What's interesting in Hujar's work generally is the fact that he's capturing someone who doesn't realize entirely that they're performing. In the John Heys images especially, Heys thinks that he’s performing for the camera, but what’s really being caught is the desperation and pathos of his attempt or desire to perform for the camera. What's interesting in that ‘58 image is that Hujar himself is mimicking something cinematic in that gesture and the way he's smoking. I agree with you to an extent, but there’s something in the gesture that's very of that moment in the fifties, and he hasn’t quite assimilated his influences.

What I love about the photograph and throughout the show is that this consistency of form makes us look at the content without being distracted. When I was in the gallery it was very busy Saturday and I would say that at least 50% of the crowd were gay couples. A few guys seemed delighted to see some of the more explicit images, like the one of the distended anus. Maybe because they were seeing this in a gallery for the first time, I don't know. But as someone who's straight, I have to overcome any initial sense of abjection. In Brutalist Readings, you write quite a lot about abjection but I'm curious about how you react to the work now you've spent so much time with it.

It's a really good question. I thought you were going to talk about the dildo image, but you went for the other one, which is more complicated in some ways. I'm not going to say I don't notice it because that’s disingenuous. What interests me about what you said about gay couples being pleased to see it in a gallery context is what is readable in it now that wasn't necessarily readable then and how it becomes readable or publicly so. So, for instance, in the room where there's Paul Thek in the woods, there's also the image with the dildo. What's interesting to me is both of those things have been or were so coded at one time. That image of Paul Thek, when it was made in 1957 was a young man lying in the woods in shorts. You could show it in the fifties and there's a sense in which a straight white American would say, “Oh, look at that young athletic boy in the woods.”

But if you were in the know, if you had the coding, then you would read it in a different way. And the fact that then on the other wall is the dildo image, which was made in 1975, a decade or so before Mapplethorpe started making images with similar subject matter. It’s still a shocking image in some sense, it’s certainly meant to be confronting. My sense would be that would have been a coterie image that he printed for friends rather than imagining that it could be exhibited in 1975.

I don't know if you saw the recent Luca Guadagnino film Queer?

No.

You don't need to see it, but I get the sense that ‘queer’ has become this heavily compacted word that means 'cool and punk and anti-heteronormative' all at once. But what does ‘queer’ mean to you? And how does it apply to Hujar?

It's complicated because it's not a word that he would’ve recognized.

Despite knowing Burroughs?

Of course. But Burroughs is playing on it in a different way to how we would think of it now. It’s often said that Peter didn’t want to be known as a gay photographer but wanted to be known as a photographer who was gay. The content of the images is what it is because that was his world … so that's what he chose to photograph. I don't think he was didactic as an artist. And yet, the work becomes political simply by dint of existing. When you ask me what ‘queer’ means in relation to him I'm reticent to overstate it, keeping in mind that that wasn't necessarily language he would have recognised then. The way the word is used now only really comes into being around the time Hujar died.

There is a timeless quality to this work. The only image in the exhibition that feels trapped in time is the political poster.

Yes, and that was done as a favour. I don't think he would've counted that as part of his oeuvre necessarily.

It feels like queer culture is increasingly being absorbed into the mainstream. You've got the Leigh Bowery show opening this weekend, Drag Race, Derek Jarman in Glasgow, and most contemporary art exhibitions I see ... I'm curious how normies utilise this stuff. For instance, as someone who is interested in Walter Benjamin, do you think cruising is an extension of the flâneur’s way of exploring the world?

When I originally started thinking about a book on Hujar, I thought he would almost stand in as a Baudelaire figure, as Baudelaire had been for Walter Benjamin. When I was saying I wanted to do a materialist history of that period in New York—or sometimes I think of it as a Balzacian approach—that has to do with being worried about versions of historicization of that period. It’s a positive that certain histories are being discovered and presented and so on, but I think there are risks in how that happens.

There were questions about the David Wojnarowicz exhibition at the Whitney in 2018. ACT UP were protesting outside because they felt that it was historicizing work in which there was still an ongoing struggle, saying isn't it great that America got over AIDS. I would hate to think that the exhibition at Raven Row did that. At the same time, how do you—to use Benjamin’s term—make the work detonate in the present? It’s a complex question.

With what's happening in America at the moment it does feel like the end of a chapter in terms of liberation struggles. In some ways, Trump represents the return of the patriarchal father, this authority figure who will tell you there are only two genders. I do wonder if the sixties generation with their liberation struggles work because they were rebelling against a father figure. Hujar lacked a father figure in growing up and his work exists right at the heart of this anti-patriarchal struggle.

That's absolutely true. We started installing the show in the week of the inauguration and I really had a strong sense of what’s inside and outside the frame. The forces outside were starting to press in harder and harder. A week after that, Trump got rid of the equalities law with regard to employment. All these exhibitions are on, but how does that speak to what's actually happening outside? What kind of leverage or criticality or conversations do they open up when the public sphere itself is more than in danger? One thing that's been gratifying about the show is that it seems to have this multifarious constituency and there have been a lot of conversations around it. But there is a fear. How do we articulate the cognitive dissonance of what's happening with the show and its perception on the one hand and then you turn the page of the newspaper and see what's happening materially in the world? How does one play out against the other? What is the use of it?

Before I visited Raven Row, I went to Tate Britain’s The 80s: Photographing Britain show and it was interesting to see it in the context of explicitly political, activist work. But one thing I thought was really interesting about your Hujar show is the formal beauty of the work. Nan Goldin covers a similar area but without anything like the same quality. How do you relate to this question of the beauty of the artwork?

When you were talking there about going to see the Eighties show ... It is very difficult to quantify why something becomes historically available at a particular moment and whether that has to do with fashion or market forces. Or, on the other side, it's something about a critical potential that becomes available at a particular moment in history. And it feels to me that all of those things are in play, but I'd like to think that it’s the latter that is the most important in this exhibition. And yes, of course, it's because the work is complex and deep enough to bear that. To me, it feels as if the Hujar show is more political now or is a more politically and critically valuable show at this moment than doing an Allan Sekula show would be for instance. Allan Sekula is a self-consciously critical artist. He’s making work in a Brechtian tradition and yet it feels historically obsolete at this moment. The bodies in Hujar’s photographs reveal what is outside or resist the forces outside the frame. There's no way in which Hujar is ever doing something like social realist photography or whatever but what he's able to register in the sensitivity of his photographic gaze, well, that can't help but be political because of what it’s able to contain. There's a sense in which the work has its moment now, not only because we can read it in certain ways or because certain images become available, but also because the work bears its present and allows it to become critical in this present.

It’s interesting that David Wojnarowicz's photos of Hujar in the moments after his death have a tension that you never get in Hujar's portraits.

You were talking earlier about the format of photographs and the way in which the repetition allows you to look at what’s in it because you don't have to deal with the formal issue. To come back to Benjamin and Baudelaire, one of the things that Benjamin found useful about Baudelaire is the way he’s still using classical form in his poetry, but the forces that it’s trying to contain are exploding out in some way. The tension between the form and the forces of modernity it's trying to contain is always present. I think there’s a tension between the form and the forces or emotions that are within Hujar’s work. It’s always pushing at the edge of what’s possible within its format.

You talked earlier about seeing the Antony and the Johnsons cover, but for me, it was A Little Life that blew me away. When I saw it, I assumed it was one of Alexander Gardner’s images of the Conspirator Payne.

I've never thought of that before, but it's so true. Hujar's work wasn’t able to get a reading at that moment in the seventies. He had a coterie of people who were interested. But you're talking about New York at the moment when Pictures Generation and October magazine were in the ascendancy and he didn't really fit.

It's interesting to me that Douglas Crimp was interested in Hujar, but was never able to write anything interesting about the work, simply because his critical architecture couldn’t work with it. There's no space to fit it in there. Hujar says he was basically doing what Julia Margaret Cameron was doing. There is a sense of embedded anachronism within the work, but that anachronism has almost become its calling card. It's become of this moment because of its anachronism.

Hujar wasn’t chasing fashion. Even in Robert Mapplethorpe, there is often this eighties glossiness.

If you pay attention in the way he was able to pay attention and you can record that attention in the way he was able to record it, then at some point it’s going to get a reading and become visible.

From his earliest beginnings, Hujar was very poor, but maybe there is an alternate universe where AIDS didn't kill people and he’s a rich celebrity photographer, like Annie Leibovitz or something.

I’m not sure he could have dealt with it, despite his very real desire to be famous.

He would’ve rejected it psychologically?

He would’ve self-sabotaged. He wouldn’t have been able to cope with it.

It is fascinating to reflect on the class aspects. Here is the work in this beautiful space owned by a millionaire Alex Sainsbury, being collected by people like Elton John … are you hanging out with Elton John every other weekend now?

I am not hanging out with Elton John.

But that's not inconceivable. Elton John is a very keen collector of photography.

Yes. Maybe that's one side of fame that Peter would have liked. He wasn't against glamour.

Thank you, John.

Peter Hujar — Eyes Open in the Dark closed on 6 April 2025.

Nude Opera: A Life of Peter Hujar is due to be published by Fitzcarraldo in 2029.

Postscript

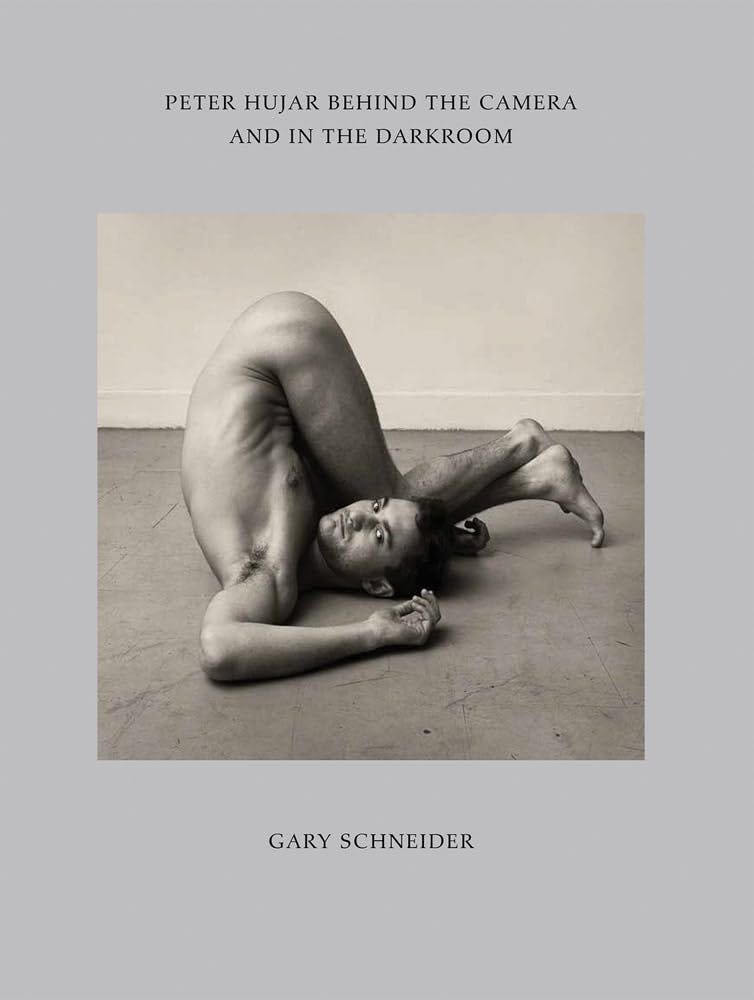

I visited Raven Row twice: once in March and once in April. On the second occasion, I wanted to consult the books the gallery had made available. I was particularly curious to read Gary Schneider’s Peter Hujar Behind the Camera and in the Darkroom, which goes into detail both about Hujar’s process of directing a sitter and creating a print.

Well, luckily for me, I found Gary Schneider himself. Here he is submitting to my request for a portrait. Alas, he can no longer do the same yoga pose he did then.

Wow! Excellent article about Hujar. I am very familiar with the photo on the cover of A Little Life since it’s one of my favorite books. It’s a heart wrenching, beautiful novel. Have you read it? - I feel silly that it never even dawned on me to look at the credit for the cover photo. I’m now going to go down the Hujar rabbit hole!

How totally fascinating, Neil.