A couple of months ago, I showed some homosexual friends the classic clip of a Ugandan news anchor asking his guest: ‘Why are you gay?’ They laughed partly at the weirdness of the Brass Eye-style questioning, but mainly at how absurd it sounds to ask such a question.

We know the answer. People are gay because they are born that way. It is a fact of nature, as confirmed by the many examples of homosexual activity in animals. Even if it wasn't, why should it concern anyone what people do in private? They are not causing others harm.

This liberal tenet, the harm principle, is now so firmly established that young people find it hard to imagine it was ever not the case.

, whose diary about becoming tetraplegic after a climbing accident comes highly recommended, wrote recently about how much attitudes have changed over the past couple of decades:Homophobia was utterly rampant when I was growing up. At my bog-standard Northern state school, to be labelled as homosexual was a death sentence in terms of the bullying, ostracization, and torment that anybody suspected of such was sure to receive. One lived in ambient caution, even if one was straight – and I can’t even imagine how awful it must have been for people who were actually gay. […] I know from experience of teaching Gen Z students that they find this effectively impossible to fathom or believe. To the vast majority of them, it’s just so obviously okay to be gay (and really not okay to be even ‘ironically’ homophobic) that they struggle to realise just how recent this change in default social attitudes is, even amongst socially-liberal demographics like university students.

It is shocking to think that gay sex was decriminalised in Scotland as recently 1980 and that, even then, the age of consent was five years higher until 2001. During the Thatcher years, the Tory government waged a culture war against left-wing councils that culminated in Section 28, a piece of legislation forbidding the promotion of homosexuality in schools.1 At the same time, thousands of gay men were dying of AIDS, which only added to the stigma. To understand what happened next, it is instructive to turn to Wolfgang Tillmans (b.1968), the fine art and fashion photographer, whose work encapsulates the long nineties.2

These days we'd call it a vibe shift. Back then, we framed culture in decades.3 A new decade meant new opportunities, which were accelerated by a series of momentous events like the fall of the Berlin wall, the rise of rave and ecstasy, the opening of EU borders, SSRIs, the Third Way ... you know the list by now. It was a time that was optimistic, carefree, and pretty directionless.

Tillmans captures the spirit of the nineties like no one else; a time when surface was depth. There is a lack of introspection in Tillmans’ portraits. Even when the subjects aren’t smiling they look pretty blank. Likewise, there is a banality in his photographs of objects. Indeed, the title of his 2003 retrospective was If One Thing Matters, Everything Matters.

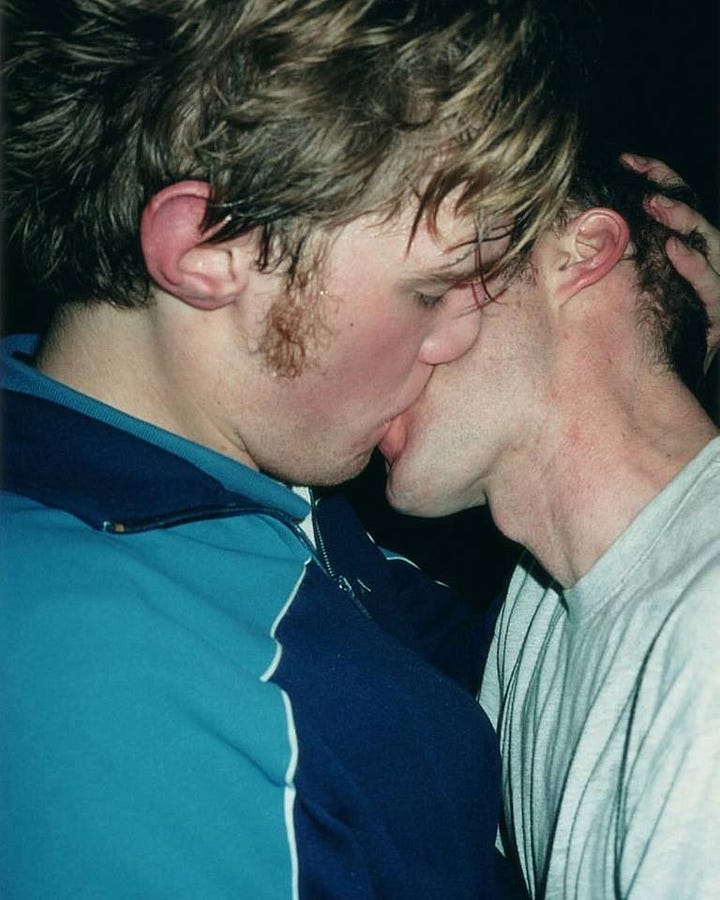

In 2000, Tillmans became the first (and so far only) photographer to win the Turner Prize. His minimalist darkroom experiments helped elevate him beyond other magazine photographers. These abstract compositions were typically combined in his exhibitions in prints of more immediate subjects such as the photo of men kissing featured on the cover of Douglas Stuart’s Young Mungo. Such juxtapositions exude a very nineties combination of ethereal blankness and edgy hedonism.

Tillmans' mission since 9/11 has been to defend liberal values against reactionary forces. In 2005 he started his truth study center, an ongoing set of displays that combat disinformation by showing the relativity of truth. As he said in a 2010 interview:

I was enraged and concerned and spending a lot of time reading media and thinking about all these different claims to the truth, ‘the big truth’ which was the ultimate justification behind all that violence and those wars. I realised that all the problems that the world faces right now arise from men claiming to possess absolute truths.4

However, by calling truth into question, Tillmans came to realise that ‘certain truths that are not negotiable […] some events and attitudes are wrong’.5

writes below: ‘any actual practice of liberal toleration will involve subjective judgment calls’.In 2016, Tillmans produced a series of self-initiated posters advocating for the UK to stay in the EU. They are pretty banal, though in a more polished way than his earlier work. For some on the left, like Sven Lütticken and Huw Lemmey, the posters came across as thoughtless and privileged, summing up the entitlement of the cosmopolitan elite, indifferent to structural violence. There is indeed nothing in Tillmans’ posters that would speak to the devastated, deindustrialised communities of the North East of England.

Yet, despite Brexit, people in Britain are overwhelmingly positive about homosexuality with 92% of people totally or fairly comfortable with a gay, bisexual, or lesbian being their neighbour, manager, GP or Prime Minister. We are all liberals. At least, for now.

In the Q&A below, Peter McLaughlin cites Adam Smith as the first liberal for showing that societies do better when they see politics as win-win rather than zero-sum. With declining living standards, we may also see a decline in social liberalism. Addressing structural inequality is beyond the neoliberal imagination. For long-nineties figures, like Wolfgang Tillmans, such subjects never enter the viewfinder.

Q&A on liberalism with Peter McLaughlin

Before writing this piece, I realised that I accept most liberal precepts without thinking. Liberalism is the water I swim in. To help get a better understanding of the topic, I asked my philosopher friend,

, to answer some questions.Peter studied philosophy at Cambridge and is now a researcher for a Lib Dem MSP in the Scottish Parliament. He was recently selected to stand for the party in the Glasgow South constituency in the forthcoming Westminster Elections.

Peter (right) speaking with

and at the first Glasgow Substack Writers Meetup on Thursday.Neil Scott: As someone who hasn’t studied it, my sense of liberalism is that it’s a philosophy that basically says: people should be able to do whatever they want as long as they don’t harm anyone. What am I missing?

Peter McLaughlin: Your ‘harm principle’ formulation of liberalism has a classic objection to it: ‘what counts as harm?’ or, in more practical terms, ‘who decides what counts as harm?’ Karl Popper’s similar principle that liberals should tolerate those who are not themselves intolerant has a similar problem, leaving open the question of what counts as ‘intolerance’ - especially difficult to decide when even the most ‘tolerant’ policy proposals typically involve the state wielding its coercive power in some way. In general, I don’t think these questions actually have well-defined, a priori answers. Any actual practice of liberal toleration will involve subjective judgment calls about which kinds of practices or beliefs can be accommodated within one’s coalition, and which are harmful to others or threatening to a tolerant society.

What was the liberal innovation? What does liberalism mean to you?

The liberal innovation, emphasised especially by Adam Smith (plausibly the first liberal) and his mentor David Hume, is the centrality of non-zero-sum politics: the primary focus of liberal politics is ‘win-win’ outcomes. Smith knew that this type of politics both required and helped create economic growth, but also that it both required and helped create more tolerant feelings about culture and social status. Where to draw the limits of toleration so as to best serve liberal political strategies depends on the context, and requires judgments to be made about that context, with different traditions inclining in different directions.

As Nietzsche writes, ‘only that which has no history has a definition’, but even if one accepts some abstract philosophical theory of what liberalism should be, it’s clear that it’s never going to capture the historical reality of all the things liberalism has been. Liberalism emerged as an approach to politics, especially in the aftermath of the French Revolution; only subsequently did it get rationalised in terms that were more philosophical than political. While philosophy has to play a role in understanding liberalism, starting with the philosophy gets things backwards.

When was peak liberalism? Aren’t we all liberal now?

Peak liberalism came before the First World War. Explicitly liberal parties held power in all of the major industrial powers except the United States and Japan. After the war the political environment was dramatically changed and the old liberal strategies were no longer enough to deal with the new political world. Liberal political parties across the world experienced splits and ruptures in this period, most dramatically in the UK, and were eclipsed. In no small part, the decline came as liberal strategies were adopted by others across the political spectrum - conservatives, the labour movement, socialists - who adapted basic liberal ideas to changing circumstances more successfully than ideological liberals themselves.

Although explicit partisan liberalism declined, liberal ideas became entrenched among other parties, liberalism was recast as an abstract, high-level political theory that could be shared across the political spectrum. Under pressure during the Second World War and the Cold War, this was even reshaped into the idea of liberalism as the defining ideology of the modern West, opposed by fascist and communist totalitarianism. This was never particularly plausible as a historical thesis, but it came to define a lot of people’s understanding of liberalism, and when the Cold War ended with victory for the West it was framed as the moment of triumph for liberalism. Certainly, liberals had much to celebrate in the demise of the Eastern Bloc; but liberalism is not the same thing as the absence of ideological conflict or the expansion of capitalism. The age of unified, self-conscious, liberal parties ruling large swathes of the world is over; what we have today is liberal ideas spread throughout various parts of the political spectrum, more or less consistent with each other, treated more or less respectfully.

There is a lot of talk about rising illiberalism and people are even describing themselves as post-liberal. What went wrong? What does liberalism lack?

If I’m blunt, ‘post-liberalism’ is a product of exactly the mistake I just mentioned: starting with philosophy instead of politics. My understanding is that the current use of the term ‘post-liberal’ can be traced back to recent conservative Catholic thinkers (although the term itself is older), who are constrained by what church dogma says about liberalism. Subsequent post-liberals have not all been Catholics, but they follow the Catholics in their reductionist understanding of liberalism: they treat it, by definition, as an individualistic ideology that takes no account of community and tradition.

Crucial for the post-liberals is the idea that liberalism is or was completely ascendant. The less sophisticated among them write as if all you need to do to prove that we should [ban surrogacy / break international obligations to asylum seekers / subsidise steel production] is to say that humans are social beings and community is important. There’s a kind of rhetorical sleight-of-hand going on here: by describing their view as ‘post-liberal’, thinkers imply (without ever proving it) that their preferred ideas are the natural alternative to liberal ones. But ‘post-liberal’ ideas are actually quite heterogeneous: some post-liberals are just contrarians, some are social conservatives, some are Blue Labour types, and some are essentially fascists.

When people talk about ‘rising illiberalism’ in an international political context, that’s the product of very different forces to educated Westerners deciding that they are ‘post-liberals’. The success of Hindutva in India (say) or the continued risk of a second Trump presidency in the US have very little to do with atomisation, and a lot more to do with the successful mobilisation of ethnic and racial hatred. Meanwhile, it was energy politics that helped enable Putin’s autocratic rule in Russia. I’m not a political scientist, and not so arrogant as to imagine I could explain and tie together these different streams. But what’s clear is that the failures of liberalism over the last two decades or so are rooted in failures at the level of political practice, of understanding and reacting to political events; the problem is not ideological individualism.

Is liberalism in decline or does it have a rosy future?

Well, the partisan liberal (and I am one) will insist that the basic ideas of liberalism are as applicable to commercial societies today as they were in the nineteenth century. But these basic ideas demand political leadership and good contextual judgment, as well as a substantial quantity of political good luck, to be implemented successfully and with lasting effect. Montesquieu once wrote that moderate politics requires ‘a masterpiece of legislation that chance rarely produces and prudence is rarely allowed to produce’. Whether you share this pessimism, it’s clear that Montesquieu had the right focus: chance and prudence, political leadership and favourable events, are what liberalism needs.

Thank you, Peter. Good luck in the election!

Stories about Section 28 have, ironically, become a key tool for teaching the next generation about homophobia with the film Blue Jean (2020), the play Maggie & Me and the forthcoming documentary, Don’t Say Gay, all using it to tell their stories. With LGBT content in education currently being debated in parliament, some fear those days are returning.

I assumed this was from 1989 to 2001, but Jeremy Gilbert argues the long 90s ended with the financial crisis in 2008.

This was also before culture got stuck.

Ibid.

Wow, wait, that Blair interview was conducted by Johann Hari? Small world.

Anyway, interesting how not knowing what the context of your piece was makes some of my answers seem a little irrelevant. Suppose it shows how slippery these kinds of ideological terms are, how much is folded into their meaning and connotations.

super good read and I learned a lot!