I'm late this week. Really late. I missed my (self-imposed) deadline by seven whole days. It's not that I didn't have anything to say; it’s more that I needed time to make a few minor adjustments.

Fortunately for me, the consequences of such a delay are minimal. I am not like William Henry Fox Talbot, who missed the chance to be known as the inventor of photography because he wanted to carry on experimenting. For me, there is no Louis Daguerre, no parvenu from across the channel, ready to steal the glory.

Louis Daguerre wasn’t the first, of course. But he refined the invention of Nicéphore Niépce. Daguerre made his first pictures in 1837, catching the attention of François Arago, the politician who announced photography to the world in 1839.

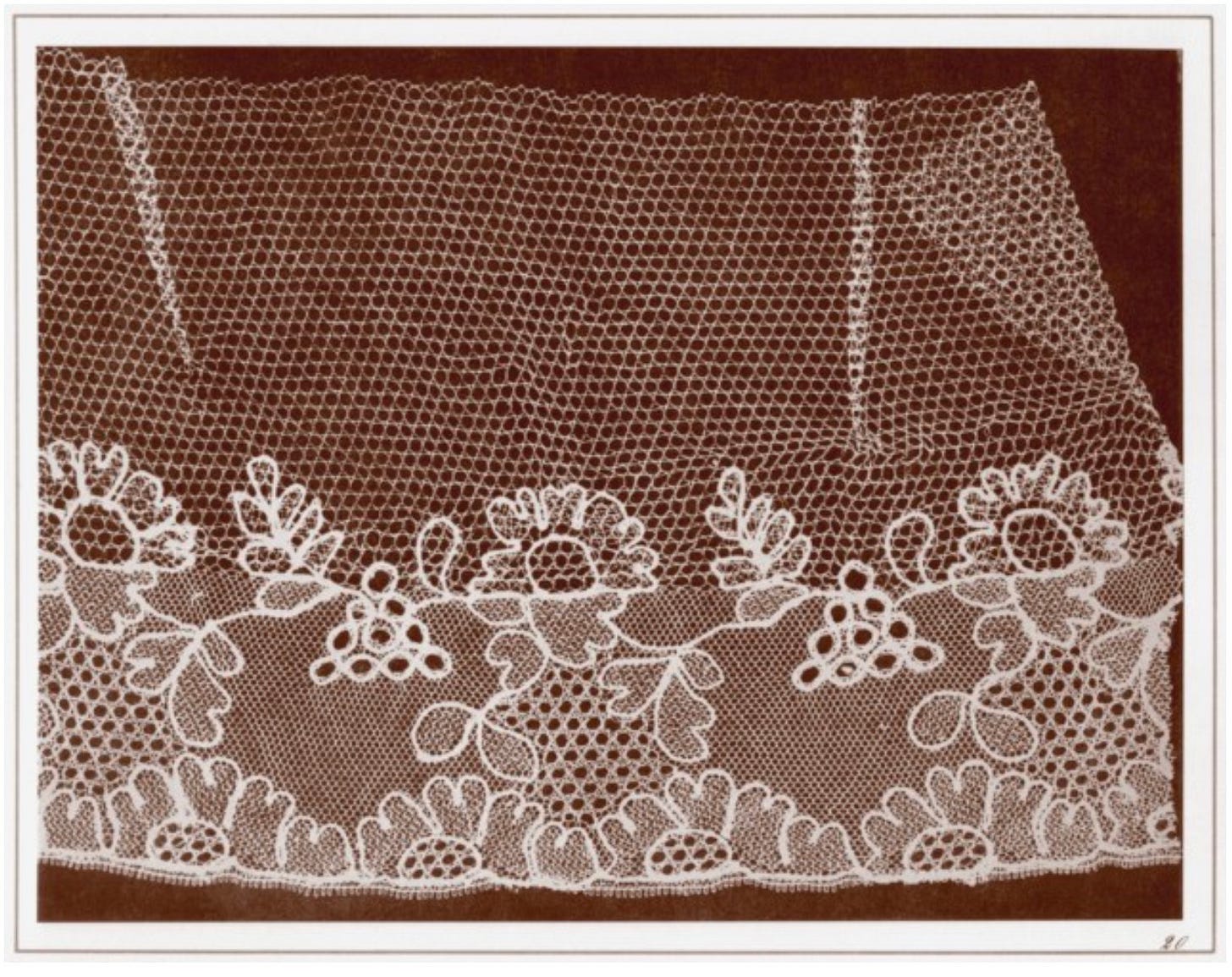

In sleepy Wiltshire, however, Talbot had been making photographs (he named them Calotypes) since 1835. Unlike the daguerreotype, which is a one-off, his process allowed for unlimited reproductions of an image. They could be printed on paper rather than just metal. He even invented the photogram, a lensless photo (later made famous by Man Ray) where one can depict the negative of a flat object placed on photographic paper.

Talbot was the archetypal gentleman inventor, tinkering with his obsessions unconcerned by fame. Can such people still exist? I wonder how many inventions remain undiscovered because we lack opportunities for idle speculation. Every spare moment is consumed by the phone. Every scientist must submit to a committee, and the days of experimenting with chemicals in the spare room are over.

From the beginning, photography was a collision of art and science. Talbot was on a tour of Europe and was badly drawing a building with a Camera Lucida when it occurred to him that it might be possible to fix the image with nitrate of silver. It is sometimes said that if you want something done quickly, ask a lazy person: they'll find the most efficient way so they can get back to idling. Photography was necessary for Talbot because buildings were so laborious to draw.

While Talbot didn't get the glory of being the inventor of photography, he is credited as the first person to create a photobook. The Pencil of Nature consists of 24 plates with accompanying texts, explaining to a world dazzled by daguerrotypes the possibilities of the new form.

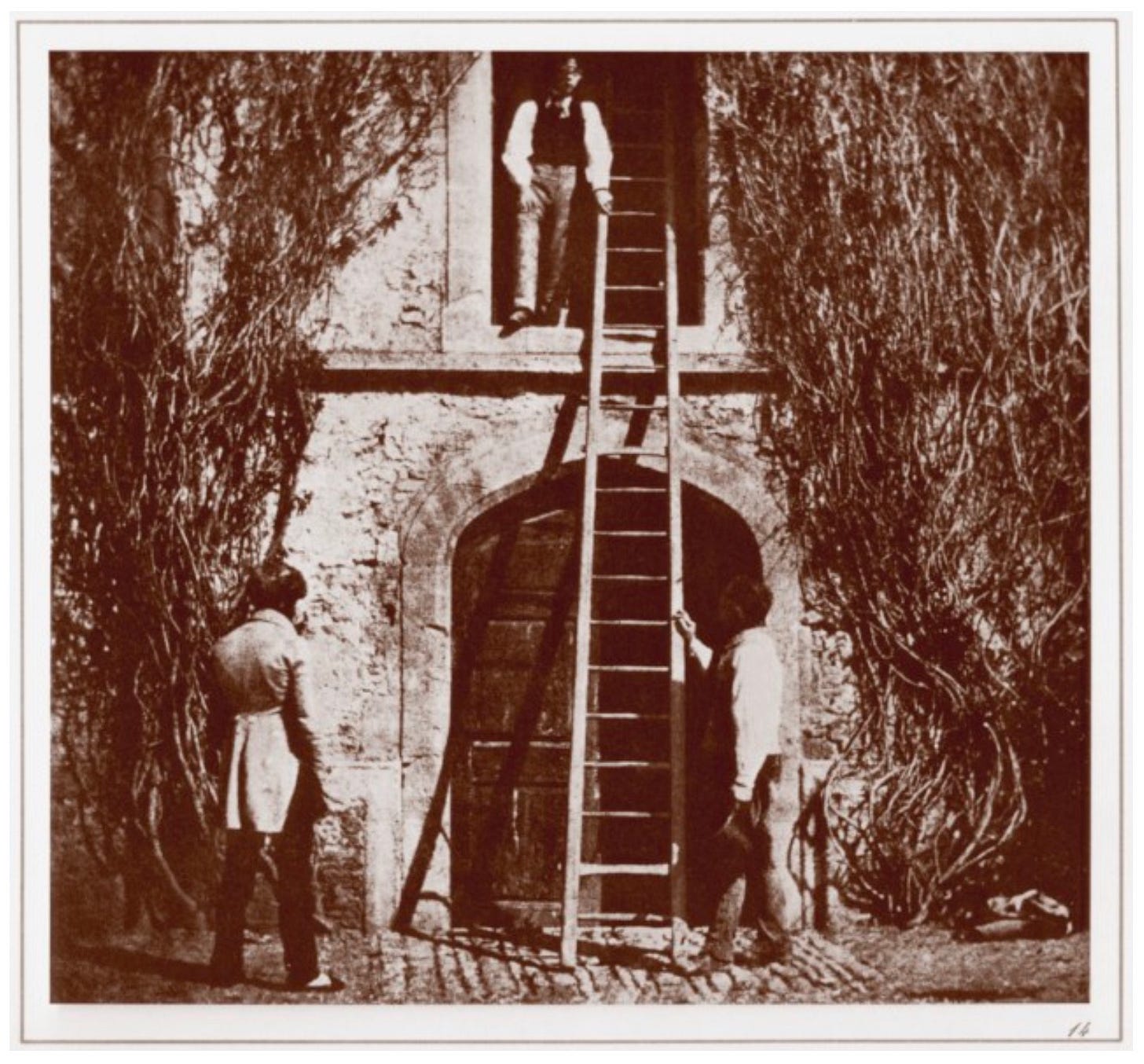

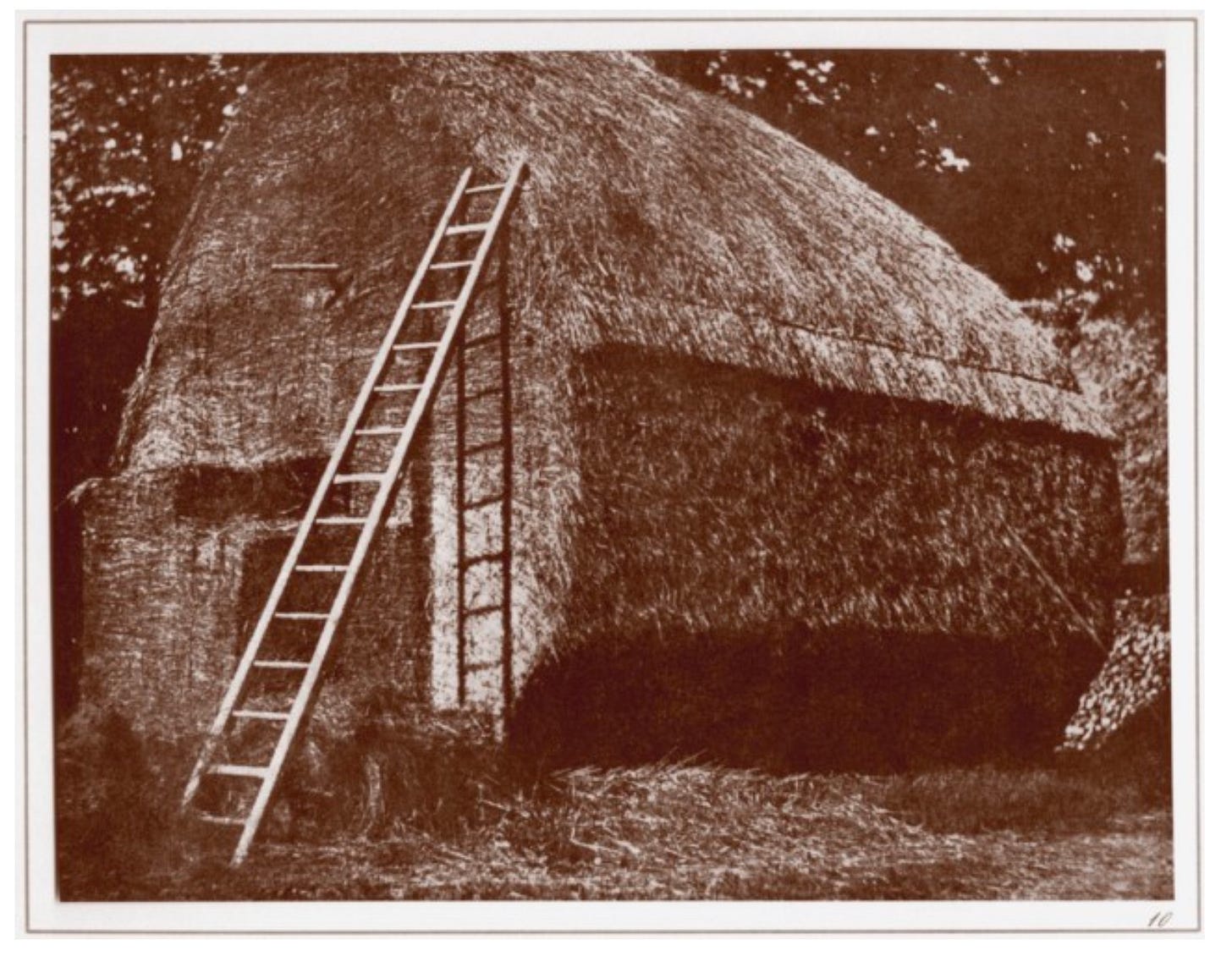

In the book, Talbot focuses mainly on buildings, ornaments, and reproductions of artworks. The long exposure times required a static subject matter. However, some photographs resonate with the excitement of the new medium.

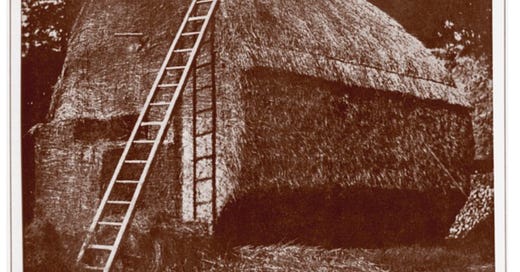

His ladders have a particular charge. One is depicted alongside workers, slightly blurred. The other is propped up against a haystack. Seeing such images produced by a machine must have been mindblowing. All that straw is depicted without alteration. The ancient practice of farming has been rendered by the modern. What a contrast! What a revolution!

The other reason I was late this week was because I was down in England visiting family. We split up the journey by stopping in Birmingham, England, where the local museum had an exhibition on Victorian Radicals. I was curious to see if there were any photographs, but it was entirely devoted to the Pre-Raphaelites.

It was striking how much their aesthetic was shaped by things that were impossible to photograph. The colours are vivid. The scenes are often imaginary. The modern, mechanised world is rejected in favour of the handmade. Talbot reminds us that however much science is involved in producing an image, there is always an artful hand behind it.

If you want to read more about my week, check out The WIP:

Much enjoyed this Neil. I read it while breakfasting about three miles from Lacock. As others have said the Fox Talbot museum there is very well worth a visit and if you do bring your camera you can also capture your own image of 'that' window.

Nice. Thank you. I visited the work of Talbot in art history classes, this was a much more fun read! Now, one might ask..... are you taking the summer off, or happily idling away while contemplating your next invention?