This week I have been drawn to photographing textures, shapes and objects. These photos are fairly abstract and likely meaningless to the viewer. In this, I suspect I'm unconsciously responding against Tish, Paul Sng's film about Tish Murtha, which I saw recently and is on BBC 4 and iPlayer this Sunday. Murtha's photographs of kids playing in Newcastle estates, as well as being unerringly well composed, are full of meaning.

There’s the surface meaning of people at play. There’s the political meaning for those aware of the deindustrialisation strategy pushed by the Thatcher government, a time when prospects diminished and disaffection spread.

Then there is a biographical meaning for those who have watched Tish and know that the people depicted are her siblings with their own stories to tell. These photos exist because Murtha was part of that community. She wasn't on a poverty safari. She wasn't afraid of being robbed. She saw it all from the inside.

So this is why I've been taking photos of objects rather than people this week. I am totally inspired by watching Tish, but couldn't imagine how to represent people’s lives as she did without there being a barrier.

It is only briefly mentioned in the film, but Murtha's own inspiration was the photojournalist Don McCullin. She drew attention to the plight of working-class Geordies much as McCullin did with the starving children in Biafra. Alas, despite commissions from The Photographer's Gallery and support from Side Gallery, Murtha never got the recognition she deserved in her lifetime. She died in poverty in 2013, aged 56, barely able to heat her house.

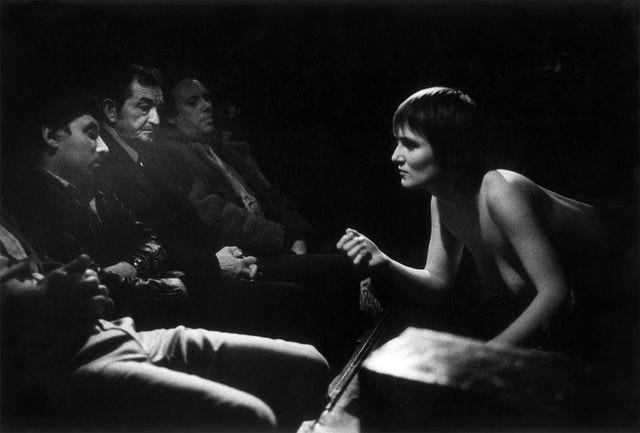

Murtha would have remained in obscurity had it not been for her daughter. Ella Murtha is the protagonist of Tish, interviewing her mother's old tutors and friends, trying to discover what she was like as a young woman. Ella learns about how Tish was vilified as the “Demon Snapper” for her project on jazz bands and how she found friends in Soho when documenting sex workers.

Both mother and daughter strongly opposed injustice. For the mother, it was the collapse of the North East. For the daughter, it is the lack of recognition for Tish's achievements. Now, with Paul Sng’s documentary, her talent is finally being celebrated.

Talking of recognition,

wrote a great post this week about the expectation that photographers will give away their work for free to get exposure. I hope that in writing these articles on photographers, I am not part of the problem. But it did make me pause and see where I stood legally.There’s a saying in the music industry: "Where there's a hit, there's a writ." Success brings money, fame ... and lawsuits. Have a number one and it won't take long for your embittered ex-guitarist to try and claim a songwriting credit.

Sometimes they are right to sue. People get greedy and it isn't fair that they should become rich off your idea. Even so, one has to weigh up whether it is worth spending one’s finite time on earth in legal limbo.

This newsletter has been pretty cavalier in sharing the work of photographers without seeking permission. The precedent for doing so is called fair dealing, which allows for the use of copyright material in criticism and reviews as long as one doesn't use too much or diminish the market value of the work. Legally, I think I am safe, but you can guarantee these arguments would be tested if I became a bestselling Substacker.

Copyright (and its subversion) has been one of the main forces behind the spread of the Internet. From Napster with music to AI systems that hoover up data for their large language models, we've seen a constant battle between what is legal and what consumers want. Some advocates for copying are open-source fundamentalists and some claim that everything is a remix. Other people seek to establish new models of digital ownership.

The legal system often feels alienating and inhuman. Cases can drag on even when it is in no one's interest for them to do so. We have deferred agency to the law gods. Just as there is folk superstition when it comes to spirituality, so there is folk wisdom when it comes to copyright. I often see incantations on tweets and YouTube videos that say:

I own nothing.

All rights go to their respective owners.

Fair Use Act 1976.

No harm intended.

For educational purposes only.

It's like throwing salt over your shoulder to scare the devil.

I knew when I saw the film last week that I wanted to write about it, but there are clear notices on her website and Instagram that no images can be used without the permission of her daughter:

All images © Ella Murtha, All rights reserved.

No usage or reproduction of any type may be made without obtaining prior written permission.

I went to the website and filled out the web form, but the form is broken didn’t do anything. There was no email alternative. I sent a message on Instagram but it remains unread.

What would you do in such circumstances? What right do I have to ignore the wishes of her daughter? Do I even need to post the photos? One of the best books on the subject, Susan Sontag's On Photography, has no images in it.

This blog is done with good intentions and doesn't make any money, but maybe it is presumptuous to use the work of others without payment. In the film, Tish's letters are full of rage towards the privileged middle classes who fetishise poverty from the comfort of the gallery. Am I exploiting her work or helping spread the message?

For Ella Murtha, this became a real issue when a graphic designer working for the singer Jamie T, restaged one of Tish's photos for a sleeve. This experience inspired Ella to write about the importance of protecting copyright, saying:

It is very important to me that I protect the Tish Murtha archive with integrity, and that I have control over where my mam's work is shown. Tish was a social photographer and saw photography as a tool for change - she was motivated by documenting real people with humanity and compassion. […] So aside from the issue of copyright protection, I feel strongly that understanding the context behind an image matters. It completes the story and helps our understanding of our social histories.

Copyright is a big issue at the moment with AI hoovering up text and images without paying artists. Sam Altman, the CEO of Open AI, claims that he wants to compensate creators but it remains to be seen how this would work in practice (he is a longstanding advocate of UBI). The most likely outcome is that users of ChatGPT won't be able to mention artists who have opted out by name. DALL-E, for instance, refused to make an image in the style of Jackson Pollock but did produce some grossly sentimental imitations of Tish Murtha.

However, because the guardrails are so strict, DALL-E can't create a photo of a child smoking.

Photography itself has a troubled relationship with rights. What rights does the subject of a photograph have? Very few, though it helps when, like Tish, you honour and respect the community.

In the early days of the cyber revolution, people like

would claim that "information wants to be free." But far from creating an enlightened world of hackers and engineers, we are distracted and dissipated. Maybe copyright enforcement can save us from being overwhelmed with information? It seems more likely that it will overwhelm us with legalese. The number of lawyers in the US has grown 793% in the last hundred years. Are we happier and more productive as a result?While artists deserve their residuals, the licensing industry has become increasingly parasitical. The other day, I received the newsletter of the comedian Stewart Lee who had to remove whole sections of his website because it included newspaper clippings with photos. He is being charged thousands of pounds in license fees by rights agencies who are scouring the web for infringements. It is good for the photographers—who get money on a no-win no-fee basis—but sad for the web.

Or take the example of the Imperial War Museum, who request a license fee for every image they’ve scanned even when it is, by any reasonable measure, long out of copyright. They’re not even making much money from charging fees; their own overheads are huge, as detailed by Jonathan Ware.

It is a terrible injustice that Tish Murtha never got the success she deserved in her lifetime and her daughter deserves to be compensated for helping to ensure her mother’s work is not forgotten. By sharing some of her photographs here I hope I am honouring, not exploiting, that legacy. Either way, I strongly recommend that you check out the documentary.1

The photographs in this article are used for criticism and review under the Fair Dealing provision of UK Copyright Law. All rights to the image remain with the photographer/copyright holder. This use does not claim any rights to the original work and is not for commercial purposes.

You put so much thoughts into this difficult topic and also covered Tish Murta. Well done! Her work is truly impressive and although I am someone who always respects copyrights, in this particular case, I am not sure whether I would have written about her / shared her photos after reading the claimer from her daughter. On the other hand and as you said, you don’t make money from it and only want to make sure -as her daughter as well - that the work of Tish is not forgotten. I would say you only acted in the best and honorable way possible. I hope you don’t get into trouble for it.

Thank you for this important topic. I once mentioned to someone here on Substack (another photographer) who posted a photograph in Notes that it would be nice to give the creator credit (I was very polite) and I ended up being verbally harassed by several trolls. I was shocked. I will never understand why (especially) photographers won’t give credit where credit is due. Wouldn’t you want this for your own work as well? Well, I guess I know your answer already! Sorry, for the rant…

A very thoughtful and helpful piece. I have had the same thoughts from time to time when writing the occasional photobook review. It may be possible to review a photobook without reproducing the photos, but it would be a challenge.

When I have done so my practice has been to produce the review then contact, the photographer either by a personal or a publisher's website. At worst I've had no response, more often a positive one. While doing it this way round - publish first, seek permission after - potentially falls foul of the letter of copyright law it means if the photographer chooses to engage he or she can see what use you are making of their work and make a judgement about whether to approve it. Since most of us who care about this kind of issue are probably the kind of people who care about photography and photographers, I suspect more likely than not permission would be granted. And if it wasn't I would simply take the post down, though that has never happened yet.