Martin Parr

Britain's most divisive photographer

There is no more divisive photographer than Martin Parr. But while almost every article about him mentions that he divides opinion, few address the value systems behind those opinions.

This week, with the help of some photographer friends—Nicky Bird, Alan Dimmick, Dina Litovsky, Neil Milton, Simon Murphy, Robbie Murrie, Olli Thomson, Anne Ward, and Christina Webber—I investigate why he is so polarising.

Humanism vs Martianism

“[Henri Cartier-Bresson] didn’t like my work. He came to a show of mine in 1996 and was very cross saying, ‘I respect what you’re doing, but I think you’re from a different planet.’”

Martin Parr1

Martian poetry was a literary movement in the late 70s and early 80s that attempted to describe the world as if through the eyes of an alien.2 Around the same time, Martin Parr was doing something similar in photography, seeing the world as inherently strange and arbitrary. Why can’t we use a box as an umbrella?

Both Parr and the Martians were responding to a change in the zeitgeist in the 1970s, namely, the collapse of the post-war humanist consensus. Whereas Henri Cartier-Bresson presents his subjects with dignity and solidarity, Parr shows their individualism and vulgarity.3

Chris Killip immersed himself in a location to understand the community and represent them respectfully and Tish Murtha was actually part of the community. With Martin Parr, it's different. He is an outsider to the people he photographs and, through his lens, humanity appears absurd.

Optimism vs Pessimism

Cartier-Bresson was the co-founder of Magnum, the cooperative photojournalism agency, known for serious black-and-white photographs from conflict zones. In 1994, a campaign was started to prevent Martin Parr from becoming a full member of the agency. Philip Jones Griffiths (PJG), who made devastating work about Agent Orange victims in Vietnam, led the charge:

[Parr is an unusual photographer in the sense that he has always shunned the values that Magnum was built on. Not for him any of our concerned ‘finger on the pulse of society’ humanistic photography. […] His penchant for kicking the victims of Tory violence caused me to describe his pictures as ‘fascistic’.4

For PJG, photography has the potential to change the world by showing the forces at play.5 This is an optimistic idea and one that Parr rejects:

How can anyone be anything but pessimistic? We are consciously screwing ourselves up. […] I would never expect my photography to change anything. That is so naive. People used to say that but they don’t say it anymore.6

This quote comes from 2010, at the height of what Mark Fisher called capitalist realism. Yet, times are changing. The last few years have seen a rise in radical activism from the likes of Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil. These groups are deeply pessimistic about the state of the world but use that as a spur to action rather than a reason to give up.7 In the age of social media, photos and videos are used to create viral outrage. While Parr has often created outrage, the message is pretty hopeless.

Impact vs Narrative

The psychologist Daniel Kahneman popularised the idea of System 1 and System 2 thinking. System 1 thinking is intuitive and instantaneous. System 2 is your considered response. Photography, at its best, works on both of these levels. It makes you look, then makes you think.

With social media, it’s easy to scroll past hundreds of images a minute. Martin Parr’s work always stops me mid-scroll. The combination of colour, composition, and human presence arrests the eyes. They have impact, but do they work as narrative? What do they add up to?

My experience is that they overwhelm the senses. They make me feel slightly nauseous. It’s like spending an afternoon in a sweet shop rather than having a meal.

Is this intentional? Well, Parr is a satirist—how can he communicate his disgust at the state of the world without making us share it?

Intention vs Outcome

“I'm not interested in doing a PR exercise. I'm trying to show the world as I find it. So often there is a sense of mischief in that work which other people can see in a different light.”8

Martin Parr

To what extent does intent matter? Who is worse: the photographer who wants to do good but ends up humiliating someone or the photographer who wants to be cruel but accidentally makes them look good?

Critics of Parr rarely go so far as to accuse him of being personally malevolent. For them, intent doesn’t matter. What matters is the outcome. As Christina Webber writes below: "Most people are judged on what they do and the direct effect they have, not their creative motivations."

Webber was inspired to write after Parr’s most recent controversy, where he wrote an introduction for a reissue of Gian Butterini’s London, a photobook accused of racism. Mercedes Baptiste Halliday said:

“(Martin Parr) represents a generation of white, middle-aged men who do what they want without any consequences. He is the institution, and we are only beginning to dismantle it.”

With photography, the effect of our images on others is difficult to guess. However, if we know people are hurt, we have some incentive to change our approach.9 By continuing to take such unsparing photographs, Parr shows that his artistic vision is more important than individual suffering. Martin Parr has given pleasure to millions. Does that outweigh the pain caused to one?

Fortunately for Parr, people like Bruce Gilden exist. Gilden's street photography is purposefully aggressive and a thousand times more intrusive than Parr's. Perhaps by interviewing Gilden, Parr helps to expand the photographic Overton Window and makes his own work seem mild by comparison.

Photographers on Martin Parr

To help understand why Martin Parr is so divisive, I contacted some of my favourite photographers to see what they thought about his work.

Here are their responses:

Robbie Murrie:

I love him, I think he blew the door open for vernacular photography. I went to an exhibition of his at Pollok House and loved it. Whenever I hear of anyone having an issue with his work it tends to be middle-class photographers but I’m from the background he’s depicting, actually maybe worse. I grew up around violence, poverty, being evicted etc so I don’t feel that discomfort, more nostalgia really.

I’ve not done a deep dive into his overseas work but personally, I don’t think I’d seek out to work in other countries. I recently described myself as a Scottish storyteller, sticking to narratives in this country, not being a culture tourist.

Check out Robbie’s website and Instagram.

Christina Webber:

Martin Parr is well aware of how his pictures will be received. He has built a career, a remarkably successful one, on poking fun in the space between pictures. And when someone like Parr gets to enjoy the privileges and platforms afforded to prestige, the praise for the cleverness of their photography, we have to credit their image-making with purpose. We need to assume that the ‘leaders’ of the photography industry, the ones with the power, know what they’re doing. That comes with culpability.

It is difficult to believe that the jibes in Parr’s pictures are accidental—he has made a living and a legacy from this for some years. A lot of the damage inflicted by Parr’s work has historically been tempered by this idea of it being playful. As someone who worked in toxic, male-dominated kitchens for a significant part of their adolescence, I would be inclined to argue that playful disrespect is the most vicious. But even giving Parr the benefit of the doubt, and believing—as I did after hearing him talk at Stills—that he really does ‘poke fun’ at Brits with the best of intentions, this only explains how he justifies his motivations for shooting. It certainly does not do anything to rectify, absolve or heal the hurt that his photographs have caused since their publication.

No matter how much attention, recognition or acclaim we receive we need to be ready to reconsider our decisions from the viewpoint of those affected by them. Most people in the world are judged on what they do and what direct effect they have, not what their creative motivations are. If someone were to point out my involvement in a project that had been understood as racist I would be horrified. It would not take 18 months of campaigning for me to apologise. But it seems too often authority and empathy seem to stand at odds. For people like Parr, even if they’ve trampled all over someone else’s property, identity, values, and sense of worth—as long as they didn’t MEAN anything by it they’re often impervious to blame. It’s exhausting.

Check out Christina’s website and gallery.

Simon Murphy:

Martin Parr knows something we don’t. He has always been twenty or thirty years ahead of the game. You put whisky in a barrel and on day one it probably doesn't taste very good. You give it ten years—wow, that tastes good. You give it twenty years—mmm, that's incredible. Thirty years—outstanding. It's about having that foresight.

He has a knack for noticing the little things that we might dismiss as “every day.” He knows it will interest us in the future. The images he shoots today are not as interesting as the ones he shot in the 70s or 80s but, with a little patience, they will be. Time will reveal what is important, but the creative has to create now while they have the time.

Without photographers like Parr, history is black and white and gritty, war and hardship. Of course, those moments should be documented but it’s not the whole picture. Sometimes we did attend a country fair where giant leeks were awarded rosettes. Sometimes we have more lipstick on our teeth than on the lips. Some people even wore socks under their sandals. Those details are evocative and in many ways give a a clearer picture of how life is and how life was. It’s those details that bring the colour, the taste and the smells right back as if it was yesterday. Those details place us right there beside lost friends and family again and bring smiles to our faces.

If the detractors just give it a little time and a little patience they might see what Martin Parr saw and thank him for the memories. There's a dangerous culture just now where everybody wants to dictate what other people should do. “You should do this, you shouldn't do that.” Most of these people are terrified to do anything. Nothing will be created if you listen to those voices. Creative people must create. That's our job.

Check out Simon’s Instagram and read the interview we did last year.

Dina Litovsky:

I didn't realize Martin Parr is divisive! I am a fan.

Check out Dina’s website and Substack.

Alan Dimmick:

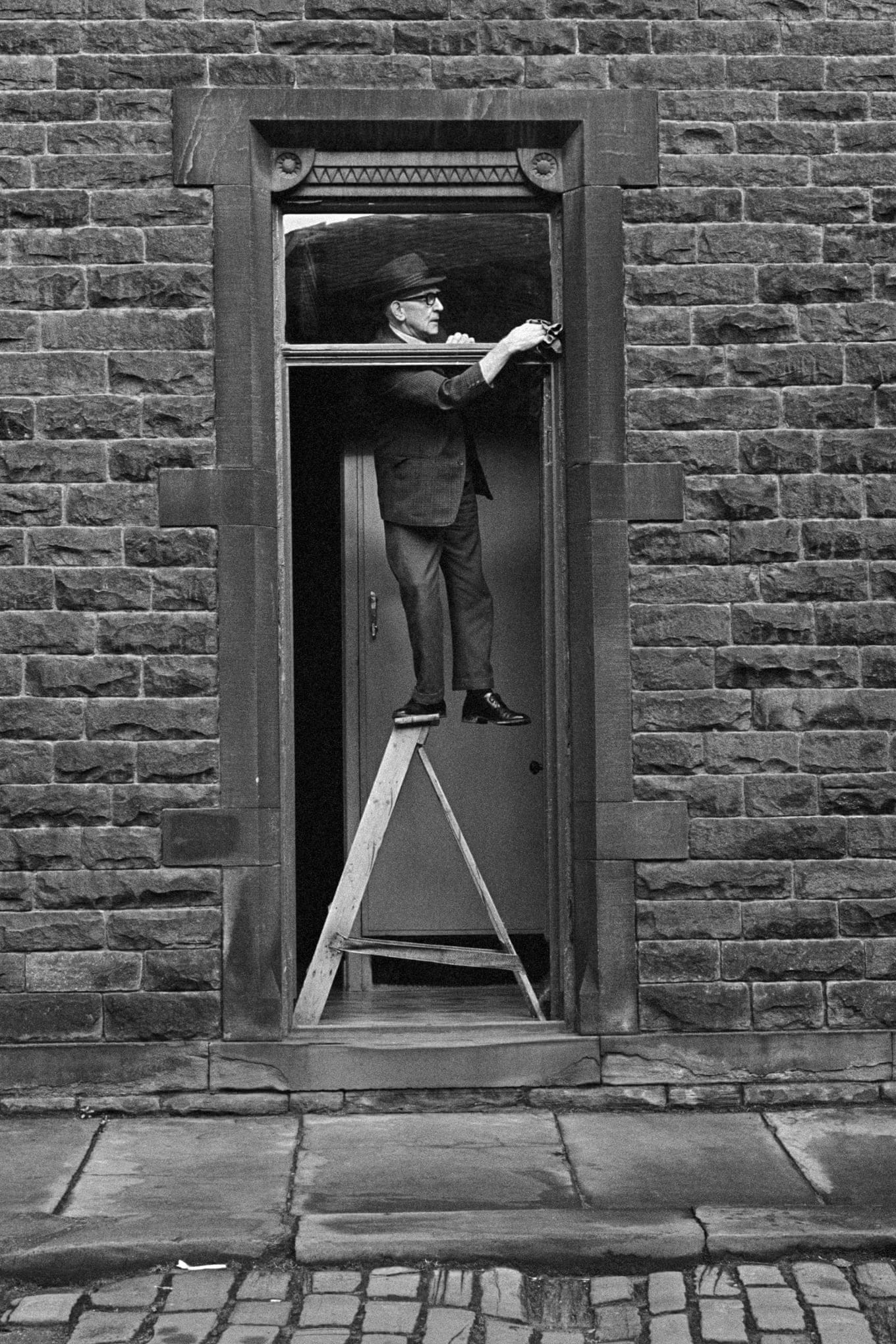

I remember seeing his New Brighton work for the first time when I was about 24. I was transfixed. I was really into the composition and the colour. The sharpness was incredible.

The Scottish book [Think of Scotland] annoyed a lot of folk because he's interested in clichés. And, you know, he's from Surrey. He is white. He’s middle class. I remember looking through it and I really liked three or four of the pictures in it, but there was a lot that was too close to home. He's an outsider looking in and, to him, that isn't a problem.

But you have to accept that all you can do is photograph things the way that you see them.

Check out Alan’s Instagram and read the interview we did two years ago.

Nicky Bird:

I was working as a darkroom technician at Watershed Media Centre in Bristol when The Last Resort was shown there in 1986. As the gallery unwrapped the framed prints, you knew that this photographer was doing something different. The colour, the fill-in flash, the ruthlessness—and the subject was working-class people. The audience’s reaction was immediate, even hostile. Although I have come to appreciate Martin Parr for championing the medium of photography, I can never quite forget this first encounter.

Check out Nicky’s Instagram and website.

Neil Milton:

The Last Resort had a profound effect on me, especially as someone who grew up working-class and had remarkably similar childhood holidays on Scotland's west coast. Rather than exploiting his subjects, Parr sees them with empathy and shows them without judgment, albeit with his trademark unblinking honesty. My photography turned in a different direction, away from Parr's bold colours and direct flash, but his work had an enduring influence, particularly the candid, wry humour. That he is, by all accounts, a lovely, supportive bloke with an unmatched passion for photobooks only endears him further.

Check out Neil’s website and Substack.

Anne Ward:

I first heard of Martin Parr when he curated an exhibition about Irish photographer John Hinde at the Museum of Modern Art in Dublin. I collected Hinde's postcards and loved the super-saturated colours and exaggerated scenes. It was a breath of fresh air to see this taken seriously as photography. After that, I got a few of Parr's books and enjoyed the way he documents everyday subjects with colour and humour.

The range of subjects he works with, from Gucci to Remote Scottish Postboxes, and the volume of work he produces is staggering. I visited the Martin Parr Foundation in Bristol last year and saw A Year in the Life of Chew Stoke Village—it was super-mundane (in a good way) and a really vivid depiction of a particular place and time that might otherwise be overlooked.

I’m not a professional photographer, but I do follow a lot of photographers (amateur and professional) and it’s easy to feel alienated by some of the debates about what is and isn’t worthy. Martin Parr’s success makes me feel more comfortable about taking photos of whatever catches my eye and seeing where it goes—for that I am grateful!

Check out Anne’s Instagram and books.

Anonymous (Female Student of Fine Art Photography):

I don't have a huge interest in his work. He's controversial mainly for his voyeuristic approach to photographing people and is known for taking photos of working-class people without asking permission and objectifying them. I don't really have much interest in street photography, but I like his book Bad Weather. His approach puts people off, and he's a middle-class white man.

I think there's a divide between artists and photographers. Most artists who use a camera would also describe themselves as photographers. But many photographers wouldn't like to describe themselves as making art. In art school, we're taught how to be artists, rather than how to use a camera, which is merely the medium we have chosen. I can tell when someone is trying to write a narrative with their photos, and then there are people who just like to capture funny or interesting moments, who hang around for ages trying to capture these.

Olli Thomson:

Ask me to name my favourite photographers and Martin Parr would be near the top of my list. These days Parr is an elder statesman of British photography, but it was not always so.

Parr's 1986 work, The Last Resort, was highly controversial among some critics. Shot in the seaside town of New Brighton, a popular destination for working-class families, his critics accused Parr of mocking his subjects. This was a time when the policies of the Conservative government were devasting working-class communities. Parr's middle-class critics saw the working class as either victims or revolutionaries deserving of sympathy and support, not Parr's perceived mockery.

When I first saw The Last Resort many years later it seemed to me the critics had missed the point. I was in my early twenties when Parr was photographing New Brighton, living in a post-industrial city badly affected by government policies, a working-class boy who holidayed every year in the same kind of seaside resorts. These were my people. To me Parr's photographs were not exploitative or mocking, they were honest. Parr showed his subjects as they were; normal people making the best of it in difficult times.

Looking back to 1986 it is hard to believe Parr was a controversial figure. Looking at his career and work in 2024 he is less 'enfant terrible', more national treasure.

Check out Olli’s Substack.

Where do you stand on Martin Parr?

The photographs in this article are used for criticism and review under the Fair Dealing provision of UK Copyright Law. All rights to the image remain with the photographer/copyright holder. This use does not claim any rights to the original work and is not for commercial purposes.

Martin Parr has told this story frequently and the wording sometimes changes. This is from 100ASA. There are other variations on PetaPixel and his FAQ. He was reconciled to Cartier-Bresson after an intervention by Martine Franck. There is a nice anecdote in the Telegraph.

“I don’t like his photos,” Cartier-Bresson said of Parr afterwards, “but he’s a nice guy.” He later sent Parr a fax of apology: “Being [an] impulsive photographer it was only once in the street that I realised how much I over-reacted to your work, which was practically unknown to me. The only fundamental thing I said when we met: ‘We belong to two different solar systems.’ And why not?”

For a sample check out A Martian Sends a Postcard Home by Craig Raine.

He also gets paid for it. The original Magnum members were usually daring war photographers like Robert Capa. They didn’t tend to work in advertising or fashion. For Colin Jacobson, such work makes Parr complicit in the evils of capitalism:

In the 80s, he seemed to be showing us the unfortunate victims of an awful society, in which greed was worshipped. But far from exposing this malaise, these advertisements make it clear that Parr is part of it. By allowing his work to appear in this way, knowing what the captions would say, and aware that the subjects of the pictures would be paid, Parr is inextricably involved in the very sickness it was said he was trying to reveal. He is part of the problem and not of the solution. Perhaps he was just sneering all along.

Here we see an attempt to assign intent and criticise outcome.

Here is the full letter, taken from Alec Soth’s blog:

I have known Marin Parr for almost 20 years and during that time I have observed his career with interest. He is an unusual photographer in the sense that he has always shunned the values that Magnum was built on. Not for him any of our concerned ‘finger on the pulse of society’ humanistic photography. He preached against us and was bold enough to deride us in print while his career as an ‘art’ photographer mushroomed…When he applied for associate membership I pointed out that our acceptance of him into Magnum would be more than simply taking on another photographer. It would be the embracing of a sworn enemy whose meteoric rise in Magnum was closely linked with the moral climate of Thatcher’s rule. His penchant for kicking the victims of Tory violence caused me to describe his pictures as ‘fascistic’ … Today he wants to be a member. The vote will be a declaration of who we are and a statement of how we see ourselves. His membership would not be a proclamation of diversity but the rejection of those values that have given Magnum the status it has in the world today. Please don’t dismiss what I am saying as some kind of personality clash. Let me state that I have great respect for him as the dedicated enemy of everything I believe in and, I trust, what Magnum still believes in.

Philip Jones Griffiths writes about his aims:

My camera has given me opportunities to witness the deceit implicit in conflicts, and my goal is to see through the deceptions. The Camera requires one to be there – a photographer is denied the luxury of philosophizing from afar.

There are photographers who are still hammering home simplistic maxims about “man’s inhumanity to man.” This affords little insight into the subject. What we need is to understand the reasons why men set out to kill one another – a good place to start would be the realm of economics. Then, perhaps we will be able to find another way to solve our differences.

From page 94 of Parr by Parr (2010).

Martin Parr scraped into Magnum by one vote, becoming its President between 2014 to 2017.

Martin Parr did take responsibility in this instance, writing:

I am embarrassed that the racist juxtaposition was overlooked. Believe me it was a mistake and I am truly sorry. This is no excuse but I'm nearly 70 years old and a white man and regretfully I'm coming to realize that sometimes I have failed to see things from another perspective. I am looking to learn and change and hopefully use my position of influence to do some good in this situation. I really am truly sorry.

Great post. I neither love nor hate Parr’s photographs. I find them a bit predictable and not very subtle but appreciate his dedication and passion for the photobook. I find his contemporaries, particularly Peter Fraser and Jem Southam, far more interesting. He seems to take up a lot of space in photography culture and, I expect, some people resent him for this. Accusations of malign intent (even overt racism) are overstated in my view. I think he is sometimes clumsy and insensitive and perhaps over-confident. He has certainly left his mark and that should be respected, if not admired. I look forward to reading more of your posts.

We need all sorts. I don’t love or gravitate to Parr’s work. I used to like it a lot more, and I still appreciate the craft and skill that the work requires. I couldn’t say his work is objectifying or lacking in empathy, because I don’t truly know how he thinks and feels about people. I may have my suspicions, but they are only based on my own sense of values and how they are reproduced through aesthetics. It doesn’t mean they are right. It’s the same with Gilden’s work, to be honest - more severe as it is - if he photographs what he loves in humanity, as he has said - maybe it is on us to see why we can’t see the beauty he sees. This may be a stretch but if you sit with the question it is not so easily dismissed.

It’s interesting to read HCB’s take, given that he is essentially the progeny of surrealism.

This isn’t exclusive to Parr, but I find much of the criticism, especially the criticism that does away with the import of intent, the criticism that confidently declares what his work is and isn’t (pretty tough to do this well with photography) says more about the critic than the art itself. The critic that has such a severe view of the work and the maker may sit a little bit closer to the fascist instinct than they may realize.